The Encounter Between Memory and Contemporaneity in Romanian Video Art

Aurelia Mihai

Vol. 11 (November 2011) by Ana Ribeiro

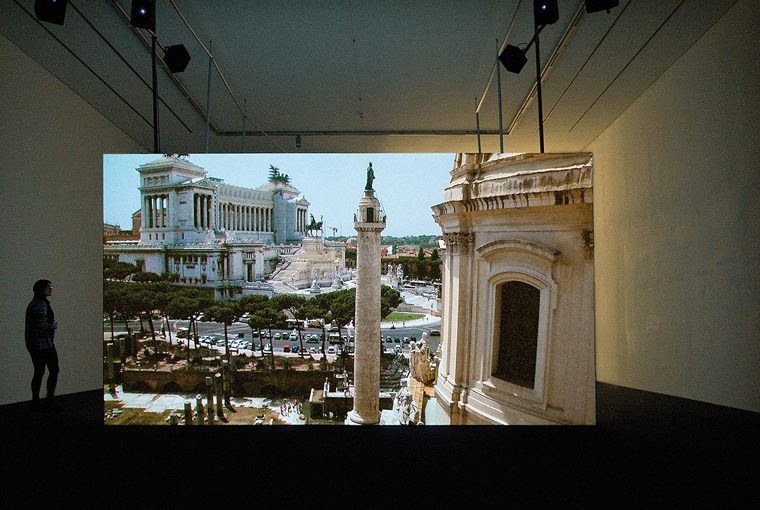

Born in Bucharest in 1968, Aurelia Mihai is one of the most interesting Romanian video artists of our time. Having studied at the Academy of Arts in Bucharest, where she obtained her diploma in 1994, she earned DAAD scholarships that allowed her to further develop her work in Dusseldorf and Cologne, Germany, studying with professors Nan Hoover, Valie Export and Jurgen Klauke. The artist has additionally obtained numerous prizes and grants in Germany and the United States and her works have been exhibited in venues such as the Chelsea Art Museum in New York and the Martin Gropius Bau Gallery in Berlin.

Mihai’s work started to draw interest from the art world with the video installation Puntea (1996). A prolific artist, she quickly created other video installations – her artistic mode of choice – with works such as Power Game (1997), Twelf secrets (1997), Endless Motion (1998), Circulation (1999), Private Spaces (2000) and This is the Hour (2002) – another highlight on her work – among others. While these early works deal with the broad idea of movement and the placement of the spectator with regards to the artwork, most of the video installations developed by Mihai more recently (in the 2000s) are at least partially related to Romanian history – or, more accurately, memory.

The unplanned trilogy formed by City of Bucur (2006), The Moldavian One (2008) and Transhumanţa (2007) deal with the figure of the shepherd, a symbol of a country that is disappearing, or at least transforming because of the requirements of modernity and contemporary politics – such as the accession of Romania to the EU. City of Bucur questions the fate of the myth of Bucharest’s founding. Using the style of a “fake making-of”, it shows the difficulties that a filmmaker and her crew encounter while shooting a representation of Bucur, the shepherd and flute player who founded the city. Nowadays this particular location has been taken over by the Romanian Parliament, Ceausescu’s House of the People. That’s why bringing and filming a shepherd here is almost impossible due to bureaucratic obstacles. This work relies on a mise-en-abîme consisting of the film-within-the-film and the film production, with directions given by Mihai herself.

Transhumanta also deals with the shock between modernity and ancient rural culture. Consisting of a two-screen video installation, it depicts the seasonal moving of sheep (the transhumanta), a tradition in Romania that has been forgotten by the modern citizen and is actually restricted by EU laws. The use of sound is of extreme importance in this work, with the anachronistic nature of the natural sheep cries contrasted with the sound of motors, cars and helicopters. This sensation of displacement is accentuated by the conclusion of the “story”: the sheep are placed in a museum, like unexpected visitors, provoking questions of authenticity and artificiality: is the presence of living animals in an art museum more artificial then their representation in paintings?

The film also had to deal with artificiality on yet another level: an important part of Romanian economy is still stock farming, but the country’s representatives think that showing it on screen gives an unfavorable image of Romania. In practical terms, it means that it is difficult for the production to obtain funding and the necessary authorization to shoot in certain areas.

Artificiality is also discussed in broader terms in Valley of the Dreamers (2004) made during the artist’s time in California. A fake documentary about Egyptologists in the USA, it shows the different types of appropriations of our conception of “Ancient Egypt”, such as the hotel in Las Vegas which provides entertainment in a conformist, uniquely western manner.

The Moldavian One is the most classic of the trilogy in terms of format and follows a documentary form focusing on shepherding. It also starts with a Romanian legend (see the interview with Aurelia Mihai in this issue), but quickly moves on to describe the shepherd’s current activity in Romania. Shortly after, threats to this activity are described: both threats to shepherding during the communist era and obstacles to shepharding in the current post-communist, EU reality.

The ancient traditions of Romania are frequently referenced in Aurelia Mihai’s work, often showing some kind of cultural or historical clash. This is the case in La Blouse roumaine (2005), where a woman rides a horse in the Lower Rhine Valley, Germany, wearing a typical Romanian blouse; it’s impossible not to relate this image to the author’s own expatriate experience. This cultural clash is also shown in a less intimate way in In the open air (2007), where Turkish and German roller skaters have a confrontation in a railway station in Hamburg. Cultural clashes, as we see, are not only between the foreigner and the native, but also between the ancient and the new, the countryside and the city.

In From time to time (2003), the traditional Moldavian bear dance is imitated. The real bears trained to dance do not exist anymore; Mihai replaces them by men wearing bearskins to reenact the animals’ performance. In The Day, it begins with the cock and ends with the dogs (2005), a rural scene in a backyard is filmed from the angle of an apartment block in Bucharest. In Solemnity moment (2005), the spectator also watches a scene that, although timeless, has been forgotten by urban contemporary Romania: an old woman twirls wool without the aid of machinery. The background sound, however, brings us to the present: it’s a Romanian broadcast about the entry of Romania and Bulgaria into the EU.

Red cinema (2009) also deals with ghosts of ancient times. It is based on a legend and staged as a fictive film: the blood of young woman brings eternal youth, be it in the 18th century “vampiresque” ambience shown in the beginning, or in the communist sanatorium where the rest of the action takes place. Once again, a radio broadcast is of great importance: it gives an account of the importance of motherhood in Ceausescu’s times, placing the female condition as inferior. The main and sole value of a woman is motherhood. Meanwhile, The Collector also deals with the relativity of values, but this time in a contemporary, semi-documentary style. A collector gathers litter, dancing with elegant movements. As Julia Draganovic (2008) puts it, “the value of the object is conveyed by the care with which it is treated.”

The work of Aurelia Mihai questions a variety of dimensions of modern life – both in Romania and universally. These dimensions range from the position of the viewer and their spatial relation to art (Where is the spectator’s place in relation to that of the image? How can the spectator circulate and develop a more intimate relation to film, scenes and its characters?), to the environment that surrounds them, to politics and culture clash – ancient versus new, foreign versus native. In this context, the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction are frequently blurred.

Aurelia Mihai thus works through a variety of styles: fiction, documentary, making-of, and more, playfully mixing them in the same or in multiple screens of her video installations. This modus operandi brings into question our perceptions of reality. In which reality would both the images shown and the audience be exist and, of course, the classic question: what is (or which perspective is) reality after all ?

Reality may be, for this artist, painfully anachronistic, and this becomes more evident in the works where she emphasizes Romanian issues in a literal fashion. Through the use of ancient traditions on screen, Mihai shows the contrast between what once was (if it still is not) recognized as her country’s identity and what the government wants Romania’s image to be in a European context. This contrast is seen as problematic. Should one see the inner elements of the identity of a country as mere memory or should it, as she does, be confronted with the contemporary world? Is its value one of artwork placed in a museum, or one that should be preserved in practical terms?

Therefore, Aurelia Mihai brings to light the importance of confronting distinct “realities” in her artwork, questioning the idea of reality itself, and, moreover, (both spatially and emotionally) from what perspective it should be seen. Experiencing Mihai’s work is experiencing contemporary clashes, in the finest form of video art.

Leave a Comment