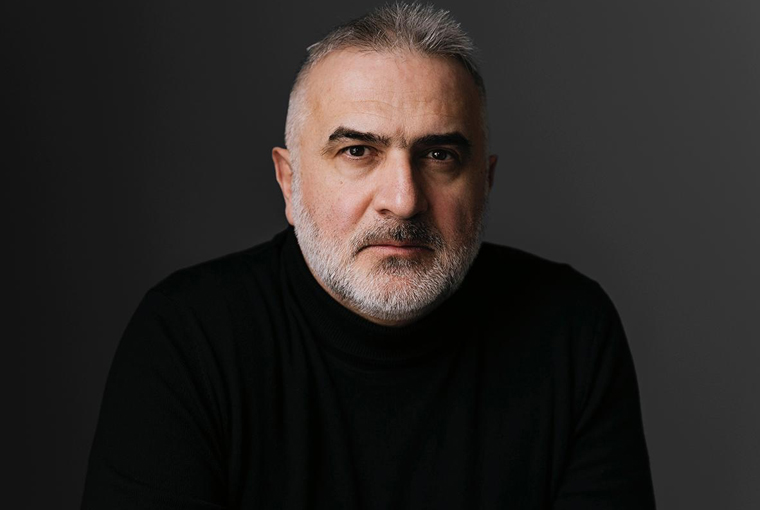

We met Konstantin Bojanov during the Trieste Film Festival (16–24 January), where his latest feature “The Shameless” was part of the main competition. Set in India, the film portrays a budding romance between two women living on the fringes of society. Bojanov reveals how the project came about, what challenges the team faced during production, and what he is currently working on.

How did you come to make this film? It’s quite an unusual movie to be made in India. How much time did you spend there, and how did immersing yourself in that society influence the story?

The project actually began in 2011. Quite by chance, I came across Nine Lives by William Dalrymple, a book of nine nonfiction stories. I didn’t know anything about the author or the book beforehand. I just picked it up at my local bookstore. My interest in and connection with India that began almost 25 years ago is what piqued my curiosity.

Initially, I wanted to make a four-part documentary, juxtaposing four stories from the book. I spent several months in India researching the short stories and clocked over 7,000 kilometers in the process. Something I was not aware of is that while some characters were real, the majority were composites, so I had to find replacement characters for the four stories that were at the core of the documentary film that I wanted to make.

I wanted to juxtapose the story of a Devadasi [a woman dedicated to worship and temple service through ritual and dance, an ancient Indian tradition that later became stigmatized and associated with prostitution] with that of a religious nun. The nun’s story was essentially a forbidden love story. Then there was the story of an untouchable – a Dalit dancer from Kerala – and of an idol maker from Tamil Nadu who come from opposite ends of the caste system. These were the four stories I wanted to focus on.

In the winter of 2014, after spending several weeks interviewing women in a Devadasi community in northern Karnataka, I began filming the first of these stories. The idea at the time was to generate some footage for the story that could help us pitch and finance the film. But as the filming progressed, I began thinking more seriously about transitioning to a purely fictional story.

What sparked that shift was the very touching relationship between the film’s central character, Rashma, and another sex worker. They were both in their early 30s, and there was a special emotional connection between them, there was a tenderness there in their relationship. I don’t know whether it was intimate or not – and it doesn’t really matter –, but it made an impression on me.

There was another element in the life of the community that I observed that I found very curious and decided to incorporate into the fictional story. Within this sort of insular community there was a caste-like system, which was based on one major differentiation: the women who were dedicated to be in the business and the women who were coming from the outside to work under the relative protection of local customs.

If there is one single positive aspect of this practice, from my point of view, it is that the business is entirely in the hands of the women. That doesn’t mean women aren’t capable of exploiting other women or even their own children. Many of the girls, when they’re very young – actually underage – are sent by their mothers to big cities like Mumbai and Pune, where they can earn more money than at home. Basically, they’re sold by their own mothers, often for almost nothing, just to work there.

This idea of an outsider on the run, taking shelter within such a community, that was the initial spark for the story. My stories always begin with a “What if?” and then develop from there. The script went through a number of major transformations. Initially, the protagonist was the younger girl, Devika. The story was told in flashbacks: in the present, she’s in her thirties and receives news that Renuka – a woman with whom she had an intense relationship in her teens and who had killed a local farmer to take revenge for her rape – is dying in prison from cancer. They haven’t seen each other in twenty years. Devika sets off, without telling her family, to go and see her.

The story was told in flashbacks, which I still liked as far as the structure was concerned, but it proved very difficult to execute. The other major transformation was making Renuka the protagonist as the more active character, and dispensing with the idea of Devika being the narrator of the story.

Talking about India, we couldn’t find a line producer willing to take on the project, or who at least believed the script could be cleared by the Ministry of External Affairs and granted the necessary permits for a foreign production to be shot in India. There wasn’t a single one who thought that could happen. Or we kept getting vague promises, hearing “yes” when it clearly was a “no.”

In the end, there were very few options for how and where we could actually make the film. That’s why we ended up shooting mostly in Kathmandu. It was primarily for those reasons, but also for budgetary ones.

So the film was actually shot in Nepal?

Entirely. Yes, the story is set in a fictional city in northern India. Initially, it was written for southern India, but that would’ve been very difficult to replicate in Nepal. We had originally planned to go into production in 2020, but the pandemic delayed things at least a couple of times. After the pandemic, the cost of production in India rose dramatically, while our budget remained the same. We made the film on a shoestring budget – at least by European standards –, which put a lot of pressure on me about the way the budget was distributed.

There’s this sort of correlation between the size of the budget and how it’s allocated, and how that impacts the artistic choices. Producing the film was extremely difficult, but honestly, I don’t care so much about that part. What was more frustrating was how many decisions were based on erroneous assumptions, often for budgetary reasons. And that affected aspects of the film to a point where I was wondering: will the film even survive?

Compromising is a slippery slope. It’s not one big decision, it’s a slow drip, drip, drip, until the bucket overflows. I highly doubt there are directors who never compromise; it’s always a matter of degree. How much you are willing to compromise is something I’m constantly grappling with to the point that if I had to compromise as much on another film, I might just stop making films altogether. I’d rather switch to writing fiction, at least that’s something that is more in my hands.

That said, I’m glad you got this one made.

Me too. Every film presents its own set of challenges. Now I’m in the middle of casting a very different film, an L.A.-based art heist story with a female protagonist as well. It was initially written to take place in Europe and I’m dealing with a very different ball game of putting together all the elements. So every project is very different. Repeating the same formulas and not taking risks is something I’m not interested in. I’d rather fail spectacularly trying something new that carries a lot of risk.

And this film, The Shameless, was exactly that, like walking a tightrope. Or maybe more like navigating a minefield. There were so many aspects of it where the odds were just stacked against me. I was directing a film in a language that I don’t speak, inside a culture I only know peripherally. That’s also another reason why I didn’t want it to be a realistic drama. I wanted to push it more into the realm of genre.

Even with the dialogue, finding someone who could adapt the English script into Hindi while keeping the tone, intonation, and stylization was a massive challenge. I didn’t want the Hindi to rely on regional dialects or vernacular, but I also didn’t want it to sound too artificial. The language had to feel adequate to the characters, their backgrounds, their levels of education. The mixture of genre and dramatic elements is always a very delicate balance.

And then there’s the question of perspective, I’m a heterosexual European man making a film about a homosexual relationship between two Indian women. I’ve been wrong about almost every single aspect in terms of how this film is going to be perceived. I was bracing myself for a wave of criticism once the film would be screened in India. But, in fact, the exact opposite happened. So far, the film has only been screened at a few festivals in India – completely sold-out shows and lines outside. That has a lot to do with Anasuya [Sengupta] winning the award for Best Actress in Cannes, but the response has been extremely positive.

Above the universal aspects of the story, people in India were also able to better understand the cultural and political subtext with which the story is infused. And that actually makes me very happy, I did not expect that at all.

You mentioned earlier how the film taps into social issues in India and globally, such as sexual and gender-based violence and the rise of political extremism. I wanted to ask whether there were any specific Indian films that inspired or influenced you. And also, as a Bulgarian filmmaker, you’ve already touched on being an outsider, encountering all those minefields. Did that perspective shape the film in any way?

I’ve been following independent Indian cinema very closely over the last two decades. Some incredibly powerful films were coming out of this movement. Ironically, a lot of that revival of independent cinema was linked to the arrival of international streamers in India. For a brief window – up until around 2020 – streamers were exempt from the country’s censorship board that regulates theatrical distribution, which made space for quite a few interesting projects. Some of these were financed or picked up by platforms, and we saw some really compelling work come out of that.

Now, of course, the climate is different. Streamers are under pressure; they’ve become much more cautious, and apparently that movement has sort of died out. The censorship rules apply to them too now, and it’s a huge market, so they’re walking on eggshells. I was actually just listening on Instagram to Anurag Kashyap talking about this. Anurag is a friend and one of the earliest supporters of the project.

I’ve probably seen every single Indian independent film of the last 15 to 20 years that you can get a hold of; it would not be an exaggeration. And the Indian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, the masterpieces that were produced at that time. Given the existence of that great tradition, it’s actually astounding that only now, for the first time in the history of the festival, an Indian actress has won the prize for Best Actress at Cannes – especially given the kind of cinema that’s been coming out of India for decades. And I’m not talking about Bollywood; I am talking about Indian auteur cinema.

That said, I can’t point to one specific film that directly influenced The Shameless, neither Indian nor Bulgarian for that matter. However strange it might sound, in terms of the structure and the story and character arc, the film that had the strongest influence on me was One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Because you have a similar character: someone in a desperate situation, someone who is on the run and who decides to enter an insulated community that operates by its own rules and rebels against it. Like Jack Nicholson’s character in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Renuka’s philosophical view of the world can be encapsulated in that she feels responsibility only for herself and her own survival.

Then she makes a full turn and ends up sacrificing everything. She is not a martyr. She is someone incredibly passionate and impulsive. One of the few things I am proud of in my career as an artist and filmmaker is having created this character, Renuka. I really like her. I love her. Actually, in all of my films I have always been attracted to characters that are sort of on the fringes of society, who live by their own moral rules that don’t necessarily comply with a conventional understanding of morality.

Another very strong influence for the character of Renuka was Aileen Wuornos, who is an American serial killer. Nick Broomfield made a great documentary twenty-five years ago called “Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer.” And the movie Monster with Charlize Theron is based on the real-life story of Aileen Wuornos. And it was also one of the first films that I asked the two lead actresses to watch as part of their preparations for The Shameless.

Can you say a little bit more about the project you are working on at the moment?

I am working on a project in Bangkok, it doesn’t have anything to do with the city itself. It is a story that takes place in Italy, a psychological thriller about a writer who comes to Italy to research her second historical novel based on the trials of Artemisia Gentileschi, the Baroque painter and her rape trial in Rome. She slowly begins to lose her grip on reality, and her mind, blurring the line between reality and imagination. The entire story takes place in Rome and Sicily.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment