After the Romanian Revolution reached its peak during the Christmas Holidays of 1989, Romania’s Communist patriarch and his wife Elena were sentenced to death by a military court and accordingly gunned down. The trial as well as the execution were filmed and televised throughout Romania and the rest of the world. For many Romanians, seeing the death of the dictator with their own eyes reenforced justice. Documentaries such as Ujica’s Videograms of a Revolution show Romanians celebrating in front of their TVs to the sound of the gunfire ending Ceauşescu’s life.

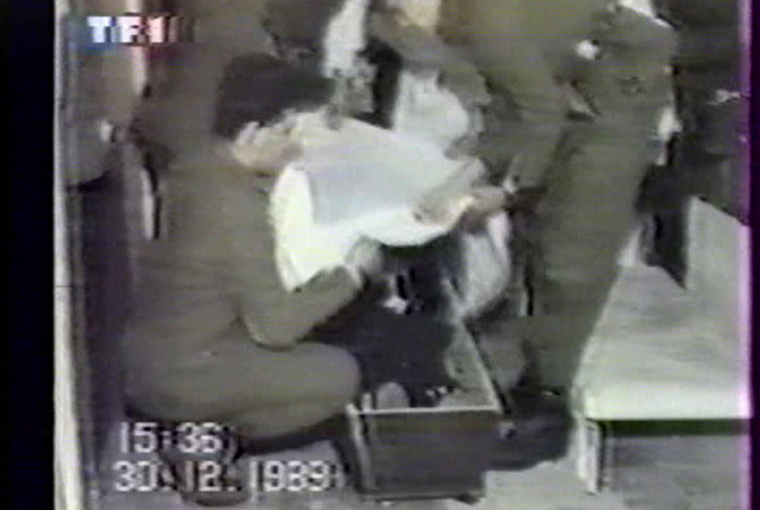

Chris Marker’s short video-collage Détour Ceauşescu documents how the execution was depicted by France’s national TV-channel TF1. As the video starts, we seem to be looking at an ordinary coverage of the event. There is a lady sitting in a studio who communicates, probably live, with her correspondents in Bucharest. But the footage used by her colleagues apparently comes from an American reporter, so that the French correspondents explaining the images are actually trying to make sense of the American commentary, not of the images themselves. And they have obvious trouble deciphering what their colleague from across the Atlantic is trying to say.

In retrospect, this commentary inflation – two French reporters commenting on the report of an American reporter for another newsreader located in France – and the confusion resulting from it, appears rather funny. At one point the American reporter sympathetically concludes from the images of clandestine soldiers fighting in Bucharest that it is necessary to “help the people of Panama achieve a democratic society.” Geography is obviously not his forte, but the same goes for the capacity of the French reporters to understand English. Their interpretation of the American’s statement has it that the fighting people are “in favor of the new government.”

Despite the journalist’s impossibility to make sense of the events in Bucharest, it would not be fair to criticize the media for these confusions, and to conclude for example that media distorts reality. Indeed, the helplessness of the journalists when trying to explain the images is not that far from reality. For many people fighting on whatever side during the Revolution, it was really not possible to tell who is fighting against who (and for what cause), and many people must have fought on more than one side. Radu Muntean’s The Paper Will Be Blue perfectly shows this identity-turmoil following a soldier through one night who is successively recognized as a representative of every possible side one can think of: soldier, revolutionary, terrorist. The only hypocrisy the media is trapped in is thus the pretension of being informed when it would make more sense to recognize the informative crisis. Only one commentator tries to admit the inevitable confusion saying that “the problem turns out to be a mess.” .

The lady back at the studio, however, seems to know exactly what is going on, saying “we have thus read a poem by Victor Hugo”, thus explaining how Victor Hugo’s quest for equality and other enlightening ideas can be compared to the situation in Bucharest. I don’t know whether this is where Marker’s collage begins, whether, for example, some of her account has been cut out between the live report and Victor Hugo’s poem. Either way, however, at this point Romania has already been confused with Panama, Revolutionaries with the State Police, so that it appears that she somehow feels the need to return to the things she is more familiar with, and sure about.

After the report on the Revolution, the grave voice of another lady aware of the historical meaning of her report announces the execution. She introduces the audience to the execution saying that the following images are “sometimes cruel and almost unbearable.” But here Marker has definitely begun with his collage, interrupting the news report with snippets of commercials. The news report really was interrupted by a commercial, but Marker altered the original footage – it is unclear however, whether he only rearranged the order of snippets from the commercials that were shown during the report, or whether he took material that best fitted the humor or irony he wanted to achieve (for example to show a slogan saying “for so much dirt, use the new SUPERCROIX!” in juxtaposition to the two corpses). The first collage-interruption is only one or two seconds long, and shows the close-up of a lady looking at something outside of the frame saying “Hm, that’s beautiful!” which Marker compares to the earnest allure of the lady announcing the last hours of the dictator.

One could argue that the meta-commentary suggested by the commercials is denouncing the news reports, and that the collage displays its subtext, namely that the journalist is not frightened or in awe, but fascinated by Ceauşescu’s execution. The fact that TF1 is responsible for making these images public, of turning a private event into a mass spectacle, obviously contradicts with the cloistered attitude of the journalist. How can one be so hypocritical, and show commercials during an event so grave as an execution? But such a critique would miss the point. The news report and the commercials don’t contradict. They are an inseparable part of the report. The killing of a dictator, or of any head of state for that matter, has always been entertaining – from historical real-life events such as the decapitations during the French Revolution, to the executions of noble men performed on stage in Shakespeare’s play – it is impossible to deny the spectacular side of dying dignitaries.

Indeed, the commercial interruptions follow the logic of the sequence before, where the confusion about the Revolution was inseparable from the report trying to make sense of it. Here, too, the images, even though they seemingly contradicted with the reporting, were still consistent, because the difficulty to identify the protagonists of the Romanian Revolution were an essential part of 1989. To say that commercials demoralize the depiction of an execution is, in my view, contrary to any execution, and especially to those of kings or dictators.

In the Europe of the middle ages public executions of criminals, traitors, and unwanted rulers were definitely more common than in the 1990s, but an interesting comparison can be drawn between, say, the executions practiced at the market cross at Cheapside, and the so-called new mediatization or commercialization of Ceauşescus’ execution. “The market cross at Cheapside…became the site at which transactions could be witnessed, proclamations read, executions performed, and condemned documents publicly destroyed” writes Jean-Christophe Agnew in his study on market places and theater. Executions were repeatedly held there and elsewhere in England, and also in other European countries, meaning that it has never been uncommon to mingle trade and commerce with horrifying public spectacles, such as executions or torturings. Capital punishment has always been a public affair.

The problem with blaming the media for making things spectacular that, under a more rational light, aren’t, not only ignores the simple fact that there is always a demand for the cruel, the hideous, and the unruly, but, more importantly, it also defies the democratic power of the law. There has to be a witness for a sentence to have its punishing effect. Public executions do not punish because a machine takes the lives of the criminals away, but, above all, because the people witnessing the executions. The unanimous judgment of a society against their ruler can be a much stronger punishment than a death sentence held out in private. Sometimes these public condemnations are necessary in order “to achieve a democratic society,” as the American reporter says. The images of Ceausescu’s death, or, more recently those showing Muammar Gaddafi’s execution, have to be publicly mediated. Be it on a market place, via television, or YouTube, spreading the news unites those who identify themselves with the judges while seeing their enemies brought to death.

Leave a Comment