Loznitsa's Countryside Revisted

Sergei Loznistsa’s Letter (Pismo, 2013)

Vol. 29 (May 2013) by Moritz Pfeifer

In his new short film Letter, Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa once again leers at his preferred subject: the Russian countryside. This time the setting is supposedly in front of a psychiatric institution although nothing in this slow-paced nostalgia sham suggests instances of lunacy. At first site, the little people that wander around so quietly over fields and woods look like ghosts or angels. This is not a metaphor. Loznitsa used some pre-Second World War lens to get the blurry halo around everything that is dressed in white, and captured the whole thing on a Soviet-era reel.

Ghosts or angels, either way, it is clear that these spirits belong to past times. As I have noted in a piece about his other two peasant documentaries, Russia’s rural society is drastically declining and Loznitsa is there to record that moment. Not without regret it seems. Letter is tinged with a melancholic sigh. There’s a scene in which two men enjoy a lunch pause having someone playing the accordion for them. In another scene a woman walks out of a house and caresses a nearby cow. As the day ends, some men have a smoke overlooking a meadow. These scenes suspiciously resemble good old social realist shots of happy peasants (as for example in some of the films of Loznits’as Ukrainian predecessor Alexander Dovzhenko who, by the way, also made three movies about the disappearing country people in a time where much of society was undergoing industrialization). Did Loznitsa finally stylize himself as a chronicler for the vanishing people in Russia’s countryside?

But then again, there’s the uncomfortable detail that all this is taking place in front of a psychiatric institution. In his film Portrait (2002), Loznitsa already established the link between the country folk and the crazy. Things are not as idyllic as they seem. The weird fogginess of the movie’s images makes it hard to believe in the purity of the rural environment which they would otherwise suggest. As in Landscape (2003), Loznitsa’s second movie about the disappearance of traditional lifestyle, the director is playing with content and style.

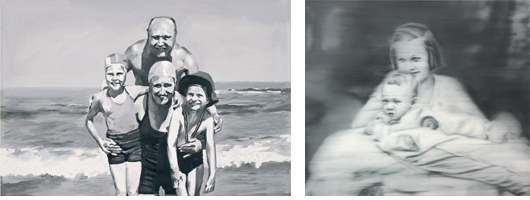

To understand this, we may compare Loznitsa’s film to some of the blurry, b+w Gerhard Richter paintings. Take a look, for instance, at one of these family paintings:

Gerhard Richter – Familie am Meer (1964) and Tante Marianne (1965)

Gerhard Richter – Familie am Meer (1964) and Tante Marianne (1965)

Richter also maintains a melancholy relationship with the past. At first sight, the painting on the left looks like any other happy-family holiday souvenir; the painting on the right like a sentimental take on childhood bliss. But the man in the picture on the left is Heinrich Eufinger, Richter’s father-in-law and Obersturmbannführer in the SS during the Second World War. He was also a physician and gynecologist who sterilized mentally ill women as part of the Nazi euthanasia program. The picture on the left depicts Richter’s Aunt Marianne who was sterilized because of her mental illness, and later killed. Richter did not reveal this information until recently, making the public believe that he is merely painting scenes from everyday middle class life. This, of course, was not strictly a lie since many families in post-War Germany dealt with their Nazi past in such a self-censoring way.

Rural or bourgeois idyll – both can work as masks hiding human tragedy. The choice of what part of reality we prefer not to see defines the reality we live in. When Eufinger died in 1988, the newspaper praised the “fruits of his scientific work”.1 There was no mention of his Nazi past, and he was, of course, never held responsible for the crimes he committed. What memories will survive? Those of happy holidays or those of doctors contributing to mass murder?

In Russia, as in many other countries, psychiatric facilities are still politically used to silence dissidents, a condition that, as the Law scholar Michael L. Perin recently showed, goes par with the wretched conditions in which “nonpolitical” individuals are held.2 In order to stigmatize political opponents by sending them to psychiatric hospitals, he observes, these institutions must first conform to certain dehumanizing standards. It is considerably harder to stigmatize someone in a psychiatric system based on social inclusion…

Better enjoy the look of a beautiful countryside. In today’s hyper-capitalist Russia, there’s a new wave of nostalgia for Stalinism, and many people surely want to believe that there is still something like an untouched countryside where mother Russia is willing to take care of her children. Richter and Loznitsa show us the downside of such dreams, namely that there is a connection between the existence of mental health institution and the cleanliness of landscapes. What must people hide from themselves to believe in the purity of their country? Watching Loznitsa’s film, we are invited to ask ourselves whether the nimbused people he portrays are just a bunch of peasants. All that glitters is not gold.

This is how I read the shortfilm The Letter:

We are in the coutryside, I do not know where. But since the director is from Belarous (or is it Russia ?) I guess it is in eastern Europe somewhere. Is there som grease put on the lens ? I cannot see things properly. As if it was kind of foggy. It is shot black and white. Shot, on celluloid, because hair can be seen in the filmgate here and there, aswas in the days of Film making.

I am not quite sure to begin with, if it is from the fifties or nowadays ? Some people shake their sheets. So it is in the morning ? I can hear indistinct voices. I see most grown up people. Some of them seem to pick hay from a truck and put it on the ground for drying up. In one scne there is a cow or is it a bull on the doorstep of a house. Many people walk into a house, for a meal ? And afterwards I can recognize two men in the foreground, one of them is eating an apple. Suddenly he steal the cap of the man in front of him, the one nearest to the camera, and put the cap on top of his own, thus making a practical joke and teasing the other guy, who quickly takes his cap back. The two men leaves and reveals a third man playing on an accordion. Finally three men is standing and walking on some kind of uneven lawn, there is a telegraph post and wires can be seen and also a house in the background. The men smoke and the white smoke they blow can be seen very distinctivly because there is a soft backlight from the sun in the late afternoon.

All the images are shot from a distance (long shot, is that what we call it ?) No moving camera. We never see people in close up, not even medium long shot. So we really do not get to know these people and why they are there. At some point I think of mentally retarded. Is it an institution for mentally retarded ? We never get to know. What we get to know, is what they do and a bit of their behaviour, they stand up in the morning, they work, they eat, they rest and they smoke. As most of us do. And as for most of us, it is impossible to get to know us fully. We walk around on this planet, seemingly with purpose and yet without no purpose.

Trygve Hagen

Filmdirector and filmteacher, Oslo Norway

Interesting reading, but what I do not believe in is the disappearance of rural life anywhere, and the denial that there can be a connection between mental health and clean landscapes. I disagree that the process of decimating rural life has a definite effect. It is a cynical vertical vision of humanity, nature and society, probably developed by the philosophers of late Capitalism, that we should reject, that can be argued and finally than can be proved false. People are different all over the world, many of us like the countryside, clean landscapes and healthy minds, and as long as there are lands where we can lead a life closer to nature, we will go there, be it a cold ambience as the one in the field, a warm Caribbean island, a hot banana republic or high in the mountains of the South.

Thought-provoking article – I really liked the juxtaposition with Richter’s work. I have yet to see the film, but it seems to do a pretty good job of addressing the issue of the ostracism of the mentally ill that is so typical of most societies these days. I wonder, though, if the heavily stylized visuals (nice stills, by the way) distract from the content somewhat – only one way to find out…