Society and Solitude

Anka and Willhelm Sasnal’s Parasite (Huba, 2014)

Vol. 39 (March 2014) by Moritz Pfeifer

Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal’s new film compares and contrasts two changing situations in the lives of two characters which the artists seem to associate with emptiness, depression, alienation, character loss and other related psychological states of mind.

The first change takes place with the retirement of an old factory worker. In the beginning of the movie the anonymous worker, a man in his 60s, undergoes a medical exam. He wanders around the city and ends up taking a rest on a river bank and is subsequently shown at home, in front of his TV set. At night, he is unable to sleep until he leaves the house in the early morning. In a dream-like sequence of the otherwise “kitchen-sink reality”-type film, as the late art historian James Cahill describes the movie’s aesthetics in a press kit, the worker breaks into the factory and spends the night there. Nostalgia galore.

The second change happens to a nameless woman who starts developing signs of melancholia when her baby is born. Unable to bond with the child, she starts wandering the city without obvious purpose. During a routine medical exam, the doctor notices that the child is underweight and that his diapers have not been changed. The mother dispassionately acknowledges the doctor’s advice. Like the worker, she ends up at the river bank and staying up all night. Although the two character’s lives seem to intersect, most drastically when the spectator realizes that they actually live together, they barely notice each other, leading separate lives.

In their personal statement the filmmakers highlight autobiographical motivations for the film. Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal grew up in Tarnów, where the film takes place, a small-sized city near Krakow. Wilhelm’s father worked in a factory and was, according to the artist, extremely attached to his job. The artists also mention that their experience as parents sometimes left them with a sense of being eaten. About their daughter, Wilhelm Sasnal says in an interview, “It was a disaster, horrible. And still she’s so absorbing, much more demanding, completely different to how our son used to be, and that’s why I painted these eaten mothers. There is this taboo – it is difficult to paint a child as a sort of parasite.”1

Left: Wilhelm Sasnal Untitled, 2011 (detail). Right: Untitled iii, 2011 (detail).

Left: Wilhelm Sasnal Untitled, 2011 (detail). Right: Untitled iii, 2011 (detail).

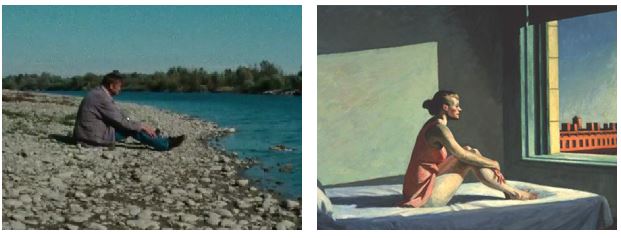

This movie is also called Parasite and deals with a similar theme. It turns Sasnal’s paintings into a cinematographic mood narrative. But the paintings highlight the psychological, indeed psychoanalytical aspect of character loss. They resemble surreal paintings, whose figurative depictions of psychological states of mind are well known. The movie, on the other hand, is realist and seems to deal with social, not psychological withdrawal. It looks more like an Edward Hopper painting, especially because of the contemplating positions in which the two main characters repeatedly are shown in. In Parasite we never see that the mother has some psychoanalytical problem being a mother. What we see is that she’s alone. There is no sequence where she communicates or interacts with other mothers or other people. The same applies to the worker. Nobody accompanies him to or picks him up from the hospital. He’s alone.

Anka and Wilheilm Sasnal Parasite (detail); Edward Hopper Morning Sun, 1952 (detail).

Anka and Wilheilm Sasnal Parasite (detail); Edward Hopper Morning Sun, 1952 (detail).

The causes of this solitude may also be different from those psychoanalysts would habitually prescribe to the attachment a man may have to his job, and a woman to her baby. The social origins of withdrawal in retirement may be due to a defunct sense of community, a society which has failed to integrate its oldest members. A similar scheme may apply to mother’s loneliness. Despite of its intent, the new Sasnal film may thus be more relevant to sociologists than to psychologists. In Poland, many people experience increasing feelings of loneliness in reaction to ongoing shifts towards greater individualism and the general atomization of social life. Traditional family structures are especially susceptible to these changes – above all the youngest and oldest members within these structures.

This would bring the Sasnal movie, again, closer to the “individual realism” of the Hopper paintings, whose lonely individuals were painted during a time in which the USA underwent radical individualization processes. As Robert D. Putnam writes in his excellent study on the decline of community bonds entitled Bowling Alone, “the roots of our lonely bowling probably date to the 1940s and 1950s”2. As for the causes for these roots, Putnam makes an argument for generational gaps. He assumes that certain events experienced in a person’s youth have an enduring impact in one’s socializing process. For the generation of post-war grown-ups in the USA such an event was WWII, which touched every family and fostered a mindset of national unity. For today’s Poland, such an event could have been the collapse of socialism. While such generational conflicts may certainly play a role, other sociologists like Claude S. Fischer and economists like Dora L. Costa and Matthew E. Kahn point out that changes towards individualization also include widening inequality, women’s increasing participation in paid labor force, in short, less time for other people because of a shift in focus on career and economic prosperity.3 Ania Plomien has shown similar trends in Poland in the last decades.4

What I want to suggest is that lone parenthood and solitary retirement, the two conditions shown in the movie, are indicators of increased individualization. They show that the natural experiences of social life are no longer collectively understood and embedded in formal, institutionalized arrangements but left to individual “choices” which, as with the two characters, enlarge the range of risks individuals have to cope with as a consequence of these choices. This, not a psychoanalytical problem of the Oedipal kind, ie. of a mother who can’t accept that there’s an “other” in her life, is what we can see in the Sasnal movie. More “others” are what the mother in this movie needs.

Leave a Comment