Constructing the West

Western Cities in the Soviet Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s

Vol. 113 (March 2021) by Pavel Stepanov

For the young Soviet state, the period from 1920 to 1930 was a period of political, economic, and cultural synchronization with the West that followed a short period of isolation. Up until the 1930s the USSR was gradually building connections with the post-WWI order, seeking military, industrial, and technological allies in the West. Along with a whole range of international agreements, which were concluded during the interbellum decades, cinema was one of the most accessible and powerful channels of cultural exchange between the Soviet Union and the West.

The Soviet film industry of the early-to-mid-1920s faced a production crisis of celluloid materials. This crisis made the USSR State Committee for Cinematography, the institution responsible for regulating the distribution process, purchase films from the USA, France, Germany, Austria and other European countries. This brought a remarkable preponderance of foreign films onto the Soviet screen. Having won popularity with the general audience, these films also provoked admiration and interest from Soviet filmmakers and theorists. Some future directors like Sergei Eisenstein and Esfir Shub worked at the so-called ‘Re-editing bureau’, where films were adjusted to the needs of Soviet ideology. They also began to produce films addressing the West. Thus, the screen presence of the West took its place and kept its position from the mid-1920s until the late 1930s. Filmmakers of the first productions of this kind were not concerned about historical authenticity and accurate representations of the West. The actor Piotr Sobolevskii, who played numerous roles in ‘Western’ films, claimed that the accurate national specificity in representing a Western state was completely detached from the script material: “I have to say that most of the films based on foreign material were made according to the following scheme: we are Russia and everything that is beyond, ‘on the other side’ is the overseas (‘zagranitsa’). Today ‘generalizations’ of this kind are rare. We learnt how to see differences between countries which not only have nothing in common with our country but stand in a remarkable contrast with it. […]. Whether it was America or France, Denmark or, for example, Spain, it did not matter. What mattered was that they were not like us”.1

Sobolevskii’s statement is significant for the purpose of this article, which examines how mise-en-scène and production design became important tools for highlighting national and cultural differences between Soviet Russia and ‘overseas’ regions. About 150 films that were produced during the 1920 and 1930s refer to the West. The ways in which the West is conceived, staged, and interpreted, can be divided into three modes of representations: as an enemy, as an ally, and as an example of progress. The following article considers these three modes of representing the West and the forms in the films Salamander (1928), Feast of Saint Jorgen (1930), Conveyor of Death (1933), Horizon (1932) and Prosperity (1932). The visual language and the numerous cultural references used in the films to construct the Soviet West on screen were formed in the vibrant and eventful context of a Western-Soviet cultural transfer, which covered various artforms from architecture and painting to literature and film.

Soviet authorities started to conduct systematic research on modern building and construction techniques in foreign countries in 1925, during the early stages of Stalin’s industrialization and urbanization program. The idea to carefully investigate the experience of international architects was introduced during the All-Union Congress for Civil and Engineering Construction of 1926. Throughout the latter half of the 1920s and the 1930s, professional architectural magazines began to publish numerous articles on architecture in Europe and the US. With the exception of these publications on Western architecture in the professional press, the growing interest for Western architecture was a response to national needs. Thus, Soviet Russia became interested in American high-rise buildings when the results of the competition to design the Palace of the Soviets (1931-1933) were announced. In 1934 the magazine Architecture in the USSR published a detailed article on American skyscrapers. Soviet-American architectural liaisons also grew especially strong in that period due to contracts with the Albert Kahn company, which designed many factories on the territory of the USSR. Contemporary Western fine art also played a significant role in the process of international cultural transfer. A cohort of institutions – the Workers’ International Relief (Mezhrabpom), the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS), the State Academy of Artistic Sciences (GAKHN), and the State Museum of New Western Art (GMNZI) – organized a series of German art exhibitions which introduced the works of leading expressionists and representatives of The New Objectivity artists such as Käthe Kollwitz, Georg Grosz, Otto Dix, Otto Nagel, Georg Scholz and many others to Soviet audiences.

The architectural and artistic exchange between the West and the Soviet Union already started during the interbellum decades, above all with (Soviet) Russia’s connection to Germany. Many of the future Soviet filmmakers were educated or trained there. For instance, the director Alexander Dovzhenko studied at the Academy of Arts in Berlin in the 1910s and maintained contact with German artists. While working for the Soviet Trade Mission in Berlin in the late 1920s, the director Mikhail Dubson visited German film studios, collaborated with local filmmakers, and produced two films. Film directors Fridrikh Ermler, Alexander Room, Leonid Obolensky, Grigori Kozintsev, cinematographers Grigori Giber, Andrei Moskvin and production designer Evgeny Yenei and others are known to have visited Germany on business in the late 1920s. Reciprocal professional exchange was formed by the visits of German filmmakers to the Soviet Union. Thus production designer and film director Heinrich Beisenherz and cinematographers and directors Joseph Rona and Michael Gold worked at the Ukrainian film studio VUFKU in the 1920s. Reports on the many Soviet directors’ trips to Germany could be found both in the professional press and in separate publications. At an institutional level, Soviet-German relations were organized via Mezhrabpomfilm, the studio of the Workers’ International Relief (Mezhrabpom), whose Soviet office in Berlin – the Prometheus Studio – distributed Soviet films abroad. Films of the studio combined ideological straightforwardness with formal experimentation. More than that, the studio produced and co-produced a great deal of films representing German communist and revolutionary movements.

Purchases of American films in 1925 opened a real era of American cinema on the Soviet screen. Its influence on Soviet art and culture was so great that after countless articles in newspapers and magazines,2 popular brochures about actors and film directors and publications about Hollywood began to appear, in which American film studios were often referred to as a “paradise”, a “country of wonders” or simply as a place of “dreams”.3

The idea of rapidly developing American cities and high-rise buildings could have been obtained from a number of Hollywood films that were released in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. Among them, one could cite the main character of High and dizzy (Hal Roach, 1920; distributed in 1925) and Safety Last (Fred Newmeyer and Sam Taylor, 1923, distributed in 1925), in both cases performed by Harold Lloyd, who literally draws the viewer’s attention to one of the New York skyscrapers. Comic circumstances force Lloyd’s character to balance on the ledge of a high-rise building in the center of the American metropolis in an attempt to return the sleeping lover to the room. He then climbs the walls of a Department store-skyscraper to catch the customers’ attention. The melodrama Skyscrapers (originally titled “Skyscraper”, Howard Higgin, 1928; distributed in 1928-1931) centers around the story of two high-rise architects falling in love with the same girl. The film opens with scenes on the scaffolding of a skyscraper and contains several episodes showing the streets of an American city. The silhouette of the high-rise coast of New York opens the film Docks of New York (Josef von Sternberg, 1928; distributed 1929-1931), which also tells the love story of a working-class man.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the question of who was considered an enemy in Soviet cultural discourse was undergoing changes. Different types of enemies can be found, ranging from fascists, foreign agents, saboteurs and spies to internal enemies like traitors of socialism and counterrevolutionary agitators. Nevertheless, one of the characteristics underlying the representation of the West as the enemy per se concerned attitudes towards religion. After the October revolution, the church was separated from the state, which produced a long process of secularization in which the country replaced past religious norms with new cults and practices. Anti-religious policies were being implemented since the beginning of the New Economic Policy (NEP) era. Workers’ clubs and specialized magazines held anti-religious campaigns and lectures, propagating an opposition to the church through science, which was claimed to be the only and sufficient form of explaining phenomena, while religion was identified as a sign of political betrayal.4 The representation of Western countries as enemies was often framed by their religious and anti-scientific worldview.

This is how the West is represented in Grigori Roshal’s Salamander (1928), a drama written by Anatoli Lunacharsky based on the biography of Austrian zoologist Paul Kammerer. The film is set in Leipzig, where the materialist Professor Zange, played by famous German actor Bernhard Goetzke, studies the adaptability of salamanders. He is harassed by the fascist aristocracy and clergy, who discredit the scientist’s experiments in newspapers. Professor Zange’s direct opponent is Bsheshinski (Sergei Komarov), a Jesuit fascist who calls him out for an open debate to challenge his scientific experiments. As the man of science comes into conflict with the man of the church and his minions, the main conflict of the film reduces to a dispute about the supremacy of science over religion. This opposition is visualized through academic debates taking place in restrained secular interiors such as scientific laboratories on the one hand, and the religious mores and rituals carried out in churches on the other. In this regard, the most important location is the neogothic Old St. Peter’s Church (rebuilt in 1882-1885 by August Hartel and Constantin Lipsius). A view on the church opens the film and the recurring shots on the building throughout the film highlight the conflict between science and religion that is at the heart of the film. The cinematographer Loui Forestier nearly always filmed the Church with medium shots or close-ups, and in some scenes, the building can be seen from below. The interiors of the cathedral were designed with an expressionist touch, underscoring the fear-provoking facet of the religious setting. The production designer Vladimir Yegorov built the set design of the temple in the pavilion with very modest means, using traditional curtain-panels and decorative pseudo-Gothic columns. The conflict between religion and science is resolved in the film’s finale, when, contrary to historical facts, Professor Zange is allowed to pursue his career in the Soviet Union, following a personal invitation by Anatoly Lunacharsky (playing himself), the People’s Commissar responsible for Ministry of Education. Thus, the Soviet Union is represented as a country of science and education, and the West is associated with religious obscurantism and political regression, which is also proclaimed by the closing title of the film: “The holy stones of Europe contain shadows, decay, and medieval backwardness.”

Salamander received mixed critical reviews. The film was praised for opening a new and important topic for Soviet cinema: “Salamander touched on a topic of great significance. The dispute between science and religion, between materialism and property, is replete with truly tragic moments that can bring rich material for cinema”.5 Some critics saw a great future in Soviet-German co-productions: “Salamander was filmed against the backdrop of a large European city, and part of the filming took place abroad, in Germany. The film is the product of a cooperation between Soviet and German film actors. Such experiences are appropriate and instructive in themselves and can only be welcomed”.6 Nevertheless, the film was also criticized for being too psychological and melodramatic; for promoting shallow entertainment and a decadent formal design: “Instead of telling a story of a progressive scientist, they give us a passive sufferer and maniac. Instead of unfolding a story of social struggle and a tragedy of the scientist, they create a sentimental melodrama about villains finishing off an unfortunate, not quite normal elderly-child.”7 The criticism of the latter review mimics the criticism against German Expressionism of the time: “Can this decadent style be a decent way to carry out our cultural cooperation of the revolutionary intelligentsia and the proletariat of the West through cinema? It seems that the style of Salamander (and the style is an expression of the worldview) is very shaky and doubtful for our revolutionary path to the West!”8

The West is represented in a similar way in Yakov Protazanov’s St. Jorgen’s Day (1930). The director had already dealt with Western themes and settings in his previous work, and was strongly influenced by European cinema throughout his career. After leaving Soviet Russia with Joseph Ermolieff in the winter of 1918-1919, Protazanov worked in France and Germany and returned to Soviet Russia in 1923. He holds a significant place in Russian film history not only because he connected the film industries of pre-revolutionary and Bolshevik Russia, but also because “he infused his Soviet films with a ‘Russianized’ version of the ‘Western style’ that audiences found so appealing. He also proved to the ‘nationalists’ among critics that a Russian can make movies that they believed were as good as American films (whether they liked them or not).”9 The production designer Vladimir Balyuzek collaborated with Protazanov in the 1910s, but apparently his education in Germany and France played a major role in shaping his artistic taste. In the sparse contemporary references, his style is defined as specifically masterful regarding historical films, but even more significantly as reflective of a designer who “feels the narrative material of films from foreign life much stronger than he does the Russian one”.10

St. Jorgen’s Day is loosely based on the novel Factory of the Saints (1919) by Danish writer Herald Bergsted. This satirical anti-religious comedy is set in the fictional city of Jorgenstadt, whose center is the Church of Saint Jorgen. Its priests subordinated the citizens to the norms of religious rites and holidays and made the Church the subject of propaganda of religious footage. The plot of the film is built around the adventures of a thief and prison escapee named Korkis (Anatoli Ktorov) and his accomplice Schultz (Igor Ilyinsky). To get hold of the treasures of the church, they embark on a new adventure and enter the cathedral pretending to be the Saint himself alongside a miraculously cured patient. The main location of this film is once again a church. Unlike Salamander, however, where the neo-Gothic Peter’s Church was supposed to represent the medieval spirit of Western Europe, the church at the center of the St Jorgen’s Day is of a different architectural style and period – the Armenian Saint Hripsime Church of Yalta (designed in 1905 by Gavriil Ter-Michelov). This building repeatedly attracted Soviet cinematographers when working with Western material. Production designer Vladimir Yegorov had used the location a few years earlier – the interiors and the stairs of the church were featured in Boris Barnet and Fyodor Otsep’s Miss Mend, a 1926 action-film, for which the designer constructed studio sets of a fictional and abstract wealthy progressive American city (“Littletown”). The interior of the church in St Jorgen’s Day is designed with simple composite panels, creating a monumental space that combines the features of a stylized Romanesque apse and a brightly lit large-scale amphitheater, where the contrasting walls are immersed in the shadow. The space is centered around a cross. Built to accommodate strong contrasts of light, such a scenery can be found in many German films of the 1920s. In this case, one can guess that the mise-en-scène designed by Vladimir Ballyuzek was inspired by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), which was accessible to some filmmakers even though it was officially banned from release in the USSR. In the scene of the sermon of the false Maria in the Metropolis cathedral, we see the same circular space, plunged into darkness at the edges and highlighted in the center.

In both Roshal’s and Protazanov’s films, darkness is perceived as a metaphor for religious obscurantism. In most other films that are embedded in the ‘West as the enemy’ model, darkness became a defining characteristic of the West as, in the words of film historian Euvgeny Margolit, “the kingdom of death or the kingdom of night”.11 Whether it was expressed in parodies of Western spy or adventure films, or so-called ‘defense films’ (oboronnii) about the impending war, the narratives involving the Western enemy were, as a rule, set in three locations: Soviet military headquarters, enemy headquarters and the battlefield. The architectural structures in films of this kind were extremely restrained and the key action was reduced to exciting chases, fights, stunts, and special effects, ironically imitating these characteristics of Western cinema.

Paradoxically, representations of Western cities as ‘kingdoms of darkness’ can also be found in films that represent the West as an ideological ally of the Soviet Union in the struggle of the working class against fascism and capitalism. In Ivan Pyriev’s first sound film The Conveyor of Death (1933), which is set in Germany in the early 1930s, members of a secret communist organization plot opposing a great forthcoming imperialist war and work towards the growth of the communist movement. The film opens with a nighttime panorama of an unnamed city, although the neon signs reveal that it is the German capital. The alluring lights of the city’s department stores, hotels, fairs, and cabarets – signs of a corrupting capitalist world – enter the bedroom of the film’s main characters, the young women Luisa, Eleanora, and Anni, in the first scene of the film. The film’s production designer Vladimir Yegorov makes the space of their corner attic with panoramic windows vulnerable and penetrable to the neon lights of city advertisements (Fig. 1, 2). The conventional architecture of their home and the surrounding area is extremely eclectic. The director himself recognized this drawback of the film: “Location footage could not be combined with the sets so the result was predictably eclectic. It was grotesque, larger-than-life, impressionistic, and naturalistic at the same time.”12 The seemingly modernist interior of the girls’ room appears to be part of an apartment in a social housing estate, testifying to the decline and poverty of its inhabitants. The world of the street, constructed by the designer with the same simple panels of the houses, continues in the theatrical room of the employment office hall and crowns the spaces of ‘the conveyor of death’ itself – the August Kron metallurgical plant. The eclectic style of the design as well as overcomplicated visual metaphors were some of the main complaints critics addressed in reviews of the film. Béla Balázs thus opened his review in the following way: “This is not a work of socialist realism. And it is not the reality of the capitalist world that this extraordinary film portrays. Actually, it bears no resemblance to any reality. The beautiful and exiting images of The Conveyor of Death are more like delirium, a naïve man’s dream about a strange reality he has only heard about.”13 Film historian Maya Turovskaya, however, sees this as a peculiar advantage of Pyriev’s film, since it reflects “an almost encyclopedic processing of all the topics of the German screen from the kammerspiel to proletarian cinema”.14 Indeed, Pyriev’s film is saturated with motifs of German cinema of the 1920s: the urban reality of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Georg Wilhelm Pabst, Lupu Pick and Fritz Lang transferred signs of contemporary architecture to the Conveyor of Death – from the grandiose windows of expensive stores and revolving doors of hotels of the capitalist world to factories that represent the world of workers as the dark side of the Western world.

It is noteworthy that these two modes of representation – showing the West as an enemy or as an ally – often use the same stylistic devices to build radically different narratives. The negative attitude towards Expressionism developed in Soviet cinema in the mid-1920s, when the People’s Commissar of Education Anatoly Lunacharsky put forward his Marxist ‘claims’ against expressionism.15 Later, not only critics, but some cinematographers also strongly criticized German cinema on similar grounds. Nevertheless, intentionally or not, the adapted techniques of German Expressionism were gradually introduced into Soviet cinema by directors and set designers. According to the filmmakers themselves, however, the works of German fine art had had a similar, if not greater, influence on them. In the memoirs of the cinematographers and production designers, the names of Käthe Kollwitz, Georg Gross and others are placed alongside the contemporary German filmmakers. However, when working with German material to construct a representation of the West onscreen, the existing attitude to cinematic expressionism was re-evaluated, and sometimes it was rather formed by the “expressiveness of the film”.16

The idea of the West as a country of progress was usually associated with the United States. Its image was formed due to the fact that many factories implemented or adapted Frederick Taylor’s scientific management theory and Fordism. Technical and managerial experience exchange programs, the construction of factories and popular literature and cinema all contributed to this association of Western progress with the United States. The plots of films about America that were released in the era of sound cinema were often based on dramatic stories of American workers who were forced to seek a better life and therefore looked for work in the Soviet Union. Examples for this narrative can be found in Vladimir Braun’s A Lad from the Banks of the Missouri (1932); Pavel Kolomoitsev’s Black Skin (1931); Georgy Tasin’s The Big Game (1934), or in the stories of returnees who were disillusioned with American life, such as Boris Shpies’ The Return of Nathan Becker (1932) and Lev Kuleshov’s Horizon (1932) – both about Jewish emigrants who had left tsarist Russia for the United States.

In Horizon, watchmaker Lev Abramovich Gorizont (Nikolai Batalov) receives an invitation from his uncle who lives in America. Gorizont dreams of America as a promised land that is free from Jewish pogroms and promises people a better life. His plans to reach America are thwarted, however, when Lev is called to the front during World War I. After deserting, he finally makes it to the coast of New York and meets his uncle. The Jewish quarter, located far away from the high-rise buildings, turns out to be a bleak area of the poor (Fig. 3), and so his dreams are thwarted once again. The world of the Jewish poor is later contrasted with the world of the capitalist city with its luxurious restaurants and expensive cars (Fig. 4). Images of progress, economic and urban development are turned upside-down: in the film, skyscrapers and luxurious homes are hostile. After the death of his uncle, there is no hope or future for Gorizont in the country of his dreams.

Films like Kuleshov’s Horizon fit into a series of agit-films that served to promote the solution of the Jewish question in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. However, if in Abram Room’s Jews on Land (1926), the resettlement of Jews to the territory of Crimea was given an epic and biblical meaning, and in Vladimir Korsh-Sablin’s Seekers of Happiness (1936), the return of a Jewish family from America to the Soviet Union and their resettlement on the territory of Birobidzhan was described as the history of the family, Horizon constructs a new image of Jewish resettlement, built on the political-ideological vision of the USA. The character of Kuleshov’s film sees America as the land of opportunities. But having been disappointed, he finds happiness on his return to Soviet Russia and replaces America as the promised land.

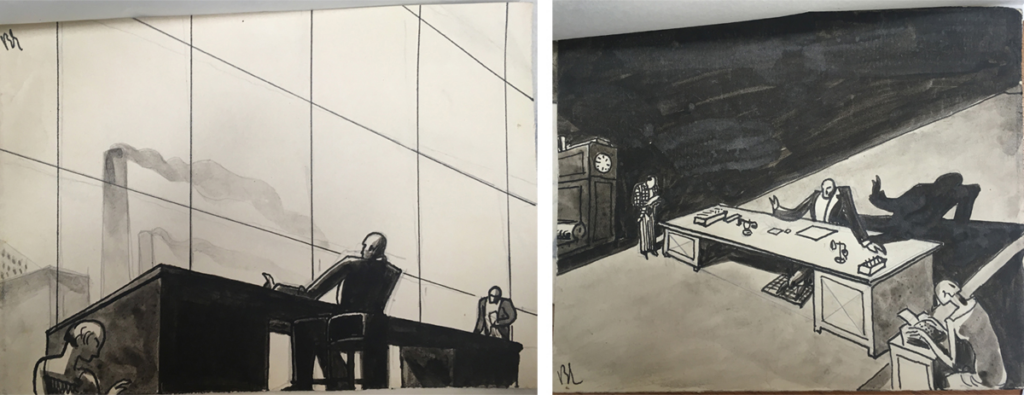

Another film of this kind is Yuri Zhelyabuzhsky’s Prosperity (1932). The film also addresses the image of the US during the Technological Revolution through the story of a workers’ union trying to organize a strike at a metallurgical plant. Unfortunately, the only way to judge the production design and the visual representation of the West in this film, is to refer to Vladimir Yegorov’s and Vladimir Baluzek’s sketches for the film that are held in the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI) (Fig. 5, 617). The images show spacious, brightly lit interiors of the offices of the head of the metallurgical plant. Judging by the size of the building’s panoramic windows, one can guess that the offices are located in a high-rise building typical of 1920 New York architecture.

The images of the West created on the Soviet screen were not so much a reflection of rare cases of professional experience by individual personalities, but rather a realization of the ideas about the West that existed in Soviet cultural discourse. Paraphrasing Australian art critic Bernard Smith, whose numerous works are devoted to postcolonial analysis of the views of European artists on the culture of indigenous Australians, the Soviet filmmaker had rarely been more than an illustrator of the convictions of the group to which he belonged, or which employed him.18 Films based on the modes of representation discussed above can thus be considered to provide a cultural mirror, which reflected the ideas of the official Soviet cultural discourse about its status and military power, its political viability in world politics, and the technological superiority of the Soviet Union. In their article analyzing the meaning of Nikolay Karamzin’s Letters of a Russian Traveler, Russian literary and cultural historians Yuri Lotman and Boris Uspenskij quote Johann Kaspar Lavater’s letter to Karamzin: “Our Eye is not designed to see itself without a mirror, and our “I” sees itself only in another “you”. We don’t have a point of view about ourselves”.19 Indeed, although providing a narrative backbone, each of the images of the West briefly considered above are set in opposition to the image of the Soviet Union. The construction of the “Western other” is an important aspect of Russian culture that was still being revised during the 1920s and 1930s, the era of the formation and strengthening of the Soviet Union between the two World Wars.

References

- 1.Sobolevskii, Piotr. Iz zhizni kinoaktera. Moscow: Isskustvo, 1967, 120-121 [Translation by author].

- 2.Jeffrey Brooks illustrates the way the official press used catchy names of popular American actors to attract readers to other publications. The 1925 issues of Pravda cited Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks’ interviews to promote Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin’’ on the Soviet screen. See, Brooks, Jeffrey. “The press and its message. Images of America in the 1920s and 1930s’’, pp. 231-252. In Fitzpatrick, Rabinowitch, and Stites. Russia in the era of NEP. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. 1991, 235.

- 3.Viktor Shklovsky’s short story “Journey to the Land of Cinema’’ focuses on the story of Kolya Petrov, a boy who found himself in America after the October Revolution. Through his eyes, readers become acquainted with the device of a movie camera and the cinema hall, and when he ends up in Los Angeles, even with Hollywood. And although in the end, the main character decides to return home to Soviet Russia, all the episodes describing the filming process present the world of Hollywood as a kind of magical Dreamland that every child wants to go to. Descriptions of film studios and behind-the-scenes life on set are supplemented with illustrations by Dmitrii Mitrokhin, who reproduces footage from famous American films.

- 4.Stites R. Revolutionary Dreams, Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution, Oxford University Press: 1988, 106.

- 5.A.S., Salamandra, `Izvestia’, 19.12.1928 [Translation by author].

- 6.Salamandra, ibid.

- 7.Khersonskii, Khrisanf, Salamandra, `Vechernyaya Moskva’, 10 dekabria, 1928, 7 [Translation by author].

- 8.Khersonskii, ibid.

- 9.Youngblood, D. Movies for the masses. Popular cinema and Soviet Society in the 1920s. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press, 1993, 120.

- 10.Kozlovskii, Sergei, Khudozhnik-architektor. Moscow: TeaKinoPechat’, 1930, 30 [Translation by author].

- 11.Margolit, Evgenii, Kak v zerkale. Germania v Sovetskom kino v 1920-1930-h godah, `Kinovedcheskiye zapiski’, no. 59, 2002. [Translation by author].

- 12.Pyriev, Ivan, O sebe i o svoyom tvorshestve, `Izbranniye proizvedenia. Tom 2’, 1978, 57 [Translation by author].

- 13.Balazs, Bela, Varvarskii talent, `Kino’, 22 oktyabrya 1933 [Translation by Olaf Möller].

- 14.Turovskaya, Maya, Zuby drakona. Moi 30-ye gody. Moscow: AST-CORPUS, 2015, 433 [Translation by author].

- 15.Neya Zorkaya summarizes the Lunacharsky’s complaints against German Expressionism in three aspects: 1) the embodiment of a dream, 2) crudity, and 3) the aptitude for a mysterious religious worldview. See, Zorkaya, Neya, Doktor Kaligari I Akakii Akakiyevich Bashmachkin. K voprosu o nemetskih vliyaniyakh v russkom revolutsionnom avangarde, `Kinovedcheskiye zapiski’, no. 59, 2002, 52.

- 16.Bagrov, Piotr, Sovetskii Expressionism, Sankt-Peterburg: Poryadok slov, 2019, 5.

- 17.Rossiiski gosudarstvennnyi arkhiv literatury I iskusstva (RGALI), Fond 2354, opis 1, ed. №36. V. Baluzek, V. Egorov, Sketches for Prosperity (1932, dir. Yu. Zhilyabuzhskii).

- 18.Smith, Bernard, European Vision and the South Pacific /Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 1950, Vol. 13. No. (1950), 100.

- 19.Lotman, Yurii, Uspenskii, Boris, `Pis’ma russkogo puteshestvennika’ Karamzina, Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1987, p. 530 [Translation by author].

Leave a Comment