Soviet Bloc(k) Housing and the Self-Deprecating ‘Social Condenser’ in Eldar Ryazanov’s Irony of Fate

Vol. 113 (March 2021) by Lara Olszowska

A completely atypical story that could happen only and exclusively on New Year’s Eve.

– Eldar Ryazanov, Irony of Fate, 1976.

Zhenya lives in apartment № 12 of unit 25 in the Third Builder Street, and so does Nadia, only that she lives in Leningrad, whereas Zhenya lives in Moscow. After a heavy drinking session at the bathhouse with friends on New Year’s Eve, Zhenya accidentally gets on a flight to Leningrad one of his friends had booked for himself. Still intoxicated on arrival, he gives his address to a taxi driver and arrives “home”. He lets himself into Nadia’s flat with his key – even their locks match – and falls asleep. When Nadia wakes him, the comical love story between the two takes center stage and the coincidence of their matching housing blocks seems to be little more than a funny storytelling device. Upon further examination it is far more significant. The misleading epigraph at the start of Eldar Ryazanov’s Irony of Fate quoted above links the ludicrous events that follow to the date on which they unfold. On New Year’s Day 1976, the film was first broadcast to television audiences across the Soviet Union, telling an extraordinary tale in a very ordinary place. This “atypical story” is not really a result of the magic of New Year’s Eve alone, but more so a product of its setting: a Soviet apartment in a Soviet housing block in a socialist city. This article applies Caroline Humphrey’s study of Soviet ideology in infrastructure and Alexei Yurchak’s writing on late socialism to Irony of Fate, suggesting that the architecture (housing blocks and the apartments within them) and infrastructure (mikroraiony1) in the film can be analyzed as self-deprecating versions of the 1920s ‘social condenser’.

The ‘social condenser’ refers to an urban concept that first appeared in the aftermath of the 1917 revolution. During the late 1920s, Soviet Constructivist architects promoted it as the new type of post-Revolutionary architecture due to the social function it was to impart.2 Its aim was to construct a new version of collectivized living that would generate enthusiasm for the regime, be it in the form of communal housing, shared civic facilities or the infrastructural organization of suburbs and cities. Victor Buchli has named Ignatii Milinius and Mozei Ginzburg’s Narkomfin Communal House of 1928 the archetypal social condenser, “a prototype for all housing of the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic”.3 It sought to instill a new socialist byt, that is daily life,into its dwellers4 by reducing the private space to a limited set of rituals (hygiene and reproduction) and maximizing the need for use of public space to perform all other aspects of living. In other words, the aim was to get neighbors to share an identical apartment and lifestyle and share a standardized subjectivity, turning them into a single productive workforce that would follow the same schedules of eating, working, exercising and relaxing together from morning to bedtime. This same logic was behind the planning of Magnitogorsk, an industrial city near the Ural Mountains that began in 1930, a project that was to incarnate the ideal “socialist city of the future”.5 However, the social condenser represented more than the physical components of communal housing or the positioning of streets, transport and factories. It was built in the hope of creating a New Socialist Person and achieving the overarching objective of mass productivity. This idealistic foundation was laid down ten years before the first brick of the never completed Narkomfin, and was the reason Magnitogorsk existed more convincingly as an idea than the confusing urban agglomeration that it had become by 1937.6 The intense focus on the city’s efficiency led officials to make rushed decisions. The city that had started with potential ended up being poorly built and highly inefficient. This demonstrates how the monumental aims of socialist ideologues promised more than they could deliver, thereby putting immense pressure on architects to build and enact their visions. This explains why many examples of social condensers now resemble the unfulfilled socialist dream rather than the realization of it. The spontaneous collapse of Soviet apartment blocks in Magnitogorsk on New Year’s Eve 20187 not only unintentionally marked the 42nd anniversary of Ryazanov’s Irony of Fate, but haunted locals with a symbolic reminder of Magnitogorsk’s failings as a social condenser. This bizarre coincidence encapsulates the exact message transmitted by Ryazanov’s fictional social condenser. Still standing or not, many of the buildings and cities initially considered beacons of hope were to end up in a state of ideological decay.

The basic principle of Marxist materialism, from which the social condenser was conceived, was that physical construction would imbue the built environment with core socialist values and encourage its residents to live according to this doctrine. However, Humphrey’s analysis indicates that the relationship between ideology and infrastructure was not this straightforward and was even less so in literature and satire. She affirms that architecture did not produce the socialist values as intended and that this is visible in imaginative works, where ideology – symbolized through a ray of light – enters a building like a prism and is refracted on its exit.8 This prismatic nature of architecture pertains also to Alexei Yurchak’s analysis of aesthetics of irony during late socialism. He maintains that forms of humor are not examples of resisting or subverting the regime’s proclaimed goals, but more a refraction of the decentered Soviet ideology that is characterized by its inherent contradictions.9 For example, Lefort’s paradox of modernity, which states that an ideology cannot claim to represent objective truth without rendering its discourse insufficient and undermining its own legitimacy,10 is the very reason socialism is contradictory. This translates into the state’s relationship with art and architecture. In its attempt to exercise control over social liberation and avant-gardist experimentation, it hinders these very processes, which should by definition be spontaneous and free from control.11 Since architecture and ideology are inextricably linked, so too are their internal paradoxes, making the social condenser the perfect tool for irony in visual art.

Painters will love to use parts of bodies, sections, and speech-makers will love to use chopped words, half-words and their bizarre cunning combinations (transrational language)

– V. Khlebnikov & A. Kruchenykh, Slovo Kak Tokovoe, 1913.12

Irony of Fate situates the Soviet housing block, a fictional yet realistic social condenser, in the late Brezhnev period. The aesthetic beginnings of Brezhnev’s housing program, known for its tower blocks organized into mikroraiony though hardly differing from the mikroraiony of the Khrushchev era,13 have been traced back to the avant-garde practices of the pre-Revolutionary period. For example, Malevich’s Black Square (1915) has been identified as “the visual manifesto for the new prefabricated panel”14 that shaped almost all new Soviet housing until the 1970s. These apartment blocks were derided as khrushchoby,15 a pejorative term still used today that combines the Soviet leader’s name and the Russian word for slum.16 An earlier influence than Suprematism was Futurism, whose poets devised a “transrational language” in 1913. Their mission was to dismantle linguistic forms and alienate words from meanings, defamiliarizing the reader from their own language while also rejuvenating it. In 1916 one of the “main strongholds” of Formalism, OPOYAZ17, was founded, with a focus on breaking dominant literary trends,18 engaging in defamiliarization or ostranenie. For Futurists and Formalists alike “the technique of art [was] to make objects unfamiliar, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself”.19 The social condenser has also been recognized as a mechanism for ostranenie20 in aesthetic terms since “Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism exercised a considerable influence on the architecture of the 1920s”.21 It equally constitutes a mechanism for political ostranenie because the ultimate aim of the condenser was to deny pre-revolutionary bourgeois styles of living and emphasize the new socialist byt. The distinction between the Soviet planners and the avant-gardists was that the former used ostranenie as a means to an end – a method through which architecture could enforce the regime – rather than the latter, who saw this process as an end in itself. This teleological basis for the social condenser is what paved the way for its self-deprecation.

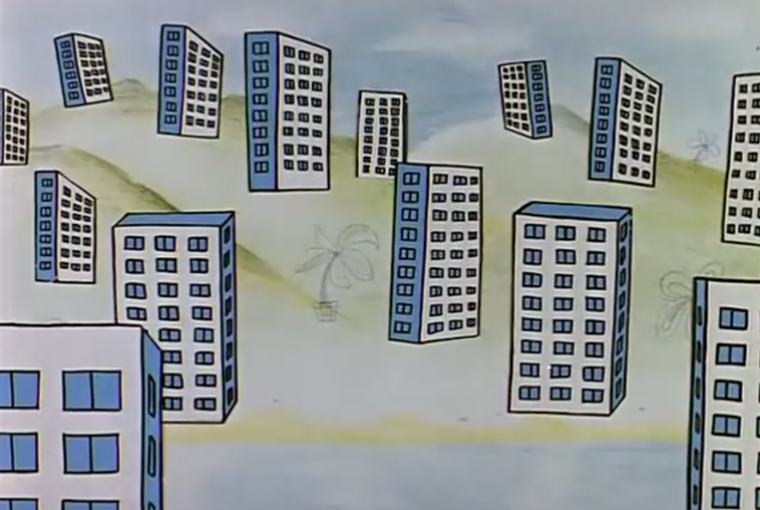

The cartoon that preludes Irony of Fate plays a multifaceted role in the opening of the film. It sets the comedic tone by making a visual mockery of architectural ostranenie and highlights that “irony had replaced the sincerity of the Thaw years”22 in late socialist comedy. In the animation, architects seek approval for their imperial-style buildings from bureaucrats, who repeatedly reject the designs until every last decorative feature has disappeared from the façade, leaving the prototypical Soviet housing block behind.23 The newly approved rectangular block shown in the cartoon has nothing “new” about it. Though delivered in a light-hearted way, the message surfaces that Soviet architects had only one option, namely to build according to the model of the prefabricated panel. Realizing his lack of creative freedom, the cartoon architect tries to find harmony at the beach, in the mountains and in the desert, but is tormented each time by rows of houses with feet marching around him.24 The inescapable army of apartment blocks in this opening sequence points to the tension between ideology and architecture that underpins the Soviet apartment block and shows how “Soviet reality itself generates comedy”.25 Only the Soviet residential program could inspire such a storyline that would poke fun at bureaucracy and lifestyle, but not so much that it was censored.26

All around everything was alien: different houses, different streets, a different life. But now it is quite a different matter. A person finds himself in an unfamiliar city, but he feels at home there.

– Eldar Ryazanov, Irony of Fate, 1976.

Beyond invoking the comedic genre, the cartoon introduces the raison d’être of Irony of Fate: the two identical housing blocks, with identical addresses, in identical mikroraiony, both inhabited by the two lead protagonists. The cartoon introduces the motif of symmetry and identicality that constitutes the very essence of the mikroraion andpermeates all levels of the film’s structure. Yet these concepts are not synonymous and lead to a conflict within the mikroraion and its ability to achieve the byt-instilling goals of the 1920s condenser from which it originates. The theme of identicality appears in the narration. A “satiric voiceover cruelly mocks the socialist concepts of urbanization”,27 namely their sameness. The voice marvels that people can feel at home in any city due to their total uniformity. Then the audience is rhetorically asked to “name one city that doesn’t haveFirst Garden Street, Second Suburban Street, Third Factory Street […] isn’t it beautiful?”. The thought likely to flicker across the viewer’s mind is that identicality is not “beautiful”, nor an inspiring ideological symbol. As Pavlik searches for Zhenya’s flat he asks a stranger where to find Third Builder Street and is met with the response “behind those tall buildings”. This momentarily exposes the impracticality of identical urban planning, tempting the knowing audience to chuckle. Such replication of streets and buildings therefore becomes a source of self-deprecation for the social condenser in the film.

Symmetry on the other hand allows the film to impart the purer values of “living socialism”28 that are genuinely shared by all, rather than bombarding the viewer with political slogans. To this end, Ryazanov creates characters who are living their lives despite ideology even though the film was made under a very politicized system.29 Even the plot’s “spatial trajectory […] presents a nearly symmetrical structure: Zhenya’s Moscow apartment—the bath house—Moscow airport—Leningrad cab—Nadia’s Leningrad apartment—Leningrad train station—Zhenya’s Moscow apartment”.30 This makes for a “pleasurable return to the status quo”31 of traditional family life without turning the film into socialist propaganda. One of the final lines in the film is Zhenya’s: “I am grateful that fate brought me to Leningrad and in Leningrad there is a certain street, with a certain housing block and a certain apartment. Otherwise, I would never be happy”. The audial symmetry found in the repetitive rhythm of this line supports the visual symmetry of the mikroraion and the fact that Zhenya’s ending is a mirror image to his start. He resides in an archetypal mikroraion with a good wife and a doting mother, no matter how much of an “adventure-seeker” Ippolit (Nadia’s ex-fiancé) says he is. The irony of fate lies within the opposing forces and outcomes of the social condenser. It can induce harmony and Soviet values whilst not overtly subscribing to socialism as seen in its self-criticism.

Humphrey calls the material object a “jumping off point for human freedom of reflection”,32 but the circularity of the plot calls this freedom into question. It is as if Ryazanov were jumping off a housing block and landing on another, thereby showing the limits to his freedom and the need to conform to tradition. Although symmetry does provide a happy resolution for the characters in the film, this freedom is rendered illusory and so contaminates the purity of the resulting harmony. The conventional ending underlines another paradox within the mikroraion. It acts as an aesthetic social condenser externally but does not construct ideal socialist worker characters inside, and instead fosters the traditional characters of husband and wife. The ironic implications of the identical blocks comprising a mikroraion are equally noteworthy. The need to present the mikroraion as such a caricature in the opening cartoon suggests that the abundant ideological signs of the Soviet period “had become transparent to pedestrians”33 and so their irony was more obvious in visual art than in daily propaganda. This echoes the 1977 image of pedestrians on Erik Bulatov’s Krasikov Street (Figure 1), seen pacing past a billboard of the mighty Lenin, oblivious to his presence. Lenin is just one example of many overused ideological symbols that the passers-by are desensitized to. He is an empty husk where ideology used to live. In Irony of Fate the same applies to architecture, though Ryazanov does not employ the same aesthetic to demonstrate the loss of ideological meaning in the social condenser.

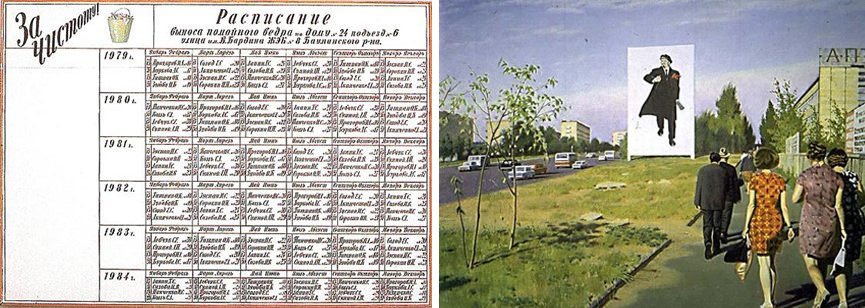

The late socialist iteration of the social condenser changed from ideological symbol to meaningless “cipher”.34 It became an ignored, “hypernormalised”35 image of Soviet reality, whose form was more important than its content. The social condenser’s modus operandi transitioned from defamiliarization in order to achieve socialism, to overfamiliarization with socialism to achieve irony. The aesthetic of the mikroraion developed from ostranenie to stiob, its exact antithesis. Stiob, a process of overidentification, achieves irony that is not straight ridicule of authority because it includes warmth and affection for the target of the joke, a relation that is comparable to Bakhtin’s carnivalesque parody.36 Ryazanov inflects his treatment of Soviet housing blocks with a similar tone, inviting his audience to laugh lovingly with – not at – the social condenser. Ilya Kabakov’s 1980 Carrying out the slop pail (Figure 2) shares the stiob-like aesthetic of Irony of Fate, in that it does not make explicit use of ideological symbols. It depicts the waste-disposal timetable for residents in an apartment block, a timetable so familiar that it is unclear whether the work retrospectively mocks or simply reminisces this ordinary aspect of Soviet life. Both Ryazanov and Kabakov put recognizable components of Soviet life before the viewer without having to use evocative ideological images to create irony. The nature of stiob is that the irony is so subtle it is not obvious whether it demands laughter or earnest appreciation and can thereby evade censorship by the party. The genius in Ryazanov’s work is that laughter appears to emanate from the farcical plot, though it is the social condenser that creates the comedy. Rather than letting mikroraiony blend into the mundane cityscape, the film exposes their existence as “neverending stiob”,37 a perfect subject of self-deprecation.

“This isn’t a home – it’s a revolving door!”

– Zhenyha, Irony of Fate, 1976.

Much like the prismatic effect of the social condenser in the film, the apartment setting of Irony of Fate uncovers the paradoxical relationship between the public and private condenser. Similar to khrushchoby and mikroraiony, space was used towards the “conception of a new ‘socialist individual’”,38 but Soviet citizens of the 70s tried to use domestic space to be free from ideology, rather than be subjected to it. The film celebrates the “sensibilities of late socialism”, namely this “retreat from the public sphere into private space”.39 People had their own small kitchen, “a haven, at least in relative terms, of privacy”, instead of the crowded shared kitchens of previous years. That said, the authorities were still not entirely comfortable with the idea of private life and so Brezhnev’s “byt involved the attempt to ensure that the privatization of the family was combined with a sense of social responsibility”.40 In other words, socialist housing continued to merge the public and private lives of its inhabitants, ensuring a fluid boundary between the two in spatial and conceptual terms41 which opposed the notion of privacy. Irony of Fate draws on the relationship between interior and communal space to illustrate the ongoing fight between the public and private to dominate domestic space and uses it to fuel comedic episodes to great effect.

At the start of the film, Zhenya’s mother sits in the kitchen to allow him and Galya some “privacy”, though she eavesdrops on every word. Members of the public invade any space that the protagonists think of as private,42 namely Ippolit, Nadia’s friends, Nadia’s mother and a group of partying strangers. To avoid being disturbed like this, Ippolit drags Zhenya out of Nadia’s flat into the corridor to interrogate him on his reasons for being half-dressed in Nadia’s bed. “Paradoxically, it was the most public space of all, the corridor, which could provide ‘privacy’”43 for this tête-à-tête. In place of the self-professed harmonious social condenser, the apartment becomes a social compressor. Limited domestic space leads to intensified emotions, unexpected behavior and explosive outbursts. Nadia smashes plates, Zhenya defenestrates Ippolit’s photograph and Ippolit starts a physical tousle with Zhenya. All of this is amplified through Ryazanov’s claustrophobic close-ups. Most powerful of all, is the shot of Zhenya and Nadia with a photo of Ippolit on the shelf between them. Somehow the public realm has managed to infect the private, even without any outsiders being physically present. Through comedy derived from Soviet life, the film exposes these tensions in front of the very people who continue existing in this seemingly ridiculous public-private condition.

The irony of the social condenser’s existence was disguised by its longevity and authority, which remained unchallenged under an enduring oppressive regime. The mikroraion could blend into daily life due to its mundane appearance. The khrushchoby had been replicated so extensively that their aesthetic was accepted. The Soviet apartment in Brezhnev’s time attracted residents who thought their own kitchen would equal privacy, though the imaginative realm revealed its paradoxes. The social condenser refracted imposed ideology rather than forcing its dwellers to conform. It seemed unable to represent or perform the function it was made for. It lost its status as an emblem of social progress, rendering itself meaningless. The social condenser as a planned city, housing block or domestic space was aligned with the revolutionary art and politics of the 1920s, but appeared ironic and stiob-like in art of the 1970s. In Ryazanov’s film the mockery of identical suburbs and the clashing of public and private pronounced the social condenser of the 1970s estrangement from its 1920s predecessor. Without having to use any overtly political statements or ideological socialist symbols, Ryazanov’s verisimilitudinous suburban housing in Irony of Fate held a mirror to Soviet viewers that New Year’s Day in 1976, as they likely watched the comedy of Soviet life from the comfort of their identical apartments.

References

- 1.Residential districts or micro-districts in the suburbs that were a key feature of Khrushchev’s housing project starting in the 1950s and continued to be built in the Brezhnev era.

- 2.Murawski, M., 2017. Revolution and The Social Condenser: How Soviet Architects sought a Radical New Society. [online] Available from: https://strelkamag.com/en/article/architecture-revolution-social-condenser [Accessed 9 November 2020].

- 3.Buchli, V., 1998. Moisei Ginzburg’s Narkomfin Communal House in Moscow: Contesting the Social and Material World. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 57(2), pp. 160–181; 387.

- 4.Buchli 1998, 161.

- 5.Kotkin, S., 1997. The Idiocy of Urban Life. In Magnetic Mountain. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 106–146; 106.

- 6.Kotkin 1997, 100.

- 7.Kramer, A., 2019. [online] Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/russia-high-rise-building-tower-collapse-explosion-soviet-housing-state-ussr-a8720686.html [Accessed 10 November 2020].

- 8.Humphrey, C., 2005. Ideology In Infrastructure: Architecture and Soviet Imagination. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 11(1), pp. 39–58; 39.

- 9.Yurchak, A. 2013 A. Late Socialism: An Eternal State. In Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–35; 35.

- 10.Yurchak 2013 A, 10.

- 11.Yurchak, A., 2013 B. Hegemony of Form: Stalin’s Uncanny Paradigm Shift. In Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 36–76; 40.

- 12.Vorobʹev, & Vorobʹev, Igorʹ. (2008). Russkiĭ avangard : Manifesty, deklaratsii, programmnye statʹi (1908-1917) : K 100-letiiu russkogo avangarda / avtor-sostavitelʹ I. Vorobʹev. Sankt-Peterburg: Izd-vo Kompozitor Sankt-Peterburg.

- 13.Attwood, L., 2010. The Brezhnev years. In Gender and housing in Soviet Russia: Private life in a public space. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 180-199; 180-181.

- 14.Stătică, I., 2019. Socialist Domestic Infrastructures and the Politics of the Body. In The Oxford Handbook of Communist Visual Cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–27; 14.

- 15.The word is not to be confused with khryuschovka, the more neutral term for block housing introduced during Khrushchev’s term.

- 16.Urban, F., 2008. Prefab Russia. Docomomo Journal, 39, pp. 18–22; 19.

- 17.Society for the Study of Poetic Language.

- 18.Erlich, V., 1973. Russian Formalism. Journal of the History of Ideas, 34(4), pp. 627–638; 627.

- 19.Shklovsky, V., 1965. Art as Technique. In Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 11–12.

- 20.Murawski, M., 2017 B. Introduction: crystallising the social condenser. Journal of architecture, 22(3), pp. 372–386.

- 21.Voyce, A., 1956. Soviet Art and Architecture: Recent Developments. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 303(1), pp. 104–115; 105.

- 22.Prokhorov, A. & Prokhorova, E., 2017. Late-Soviet Comedy: Between Rebellion and the Status Quo. In Film and Television Genres of the Late Soviet Era. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 107–148; 115.

- 23.Fedina, O., 2013. The Irony of Fate (or, Enjoy Your Bath!) In What Every Russian Knows (And You Don’t). London: Anaconda Editions, pp. 1–11; 5.

- 24.Lesskis, N., 2005. Fil’m Ironiya sud’by…: ot ritualov solidarnosti k poetike izmenennogo soznaniya. Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, (Moscow, Russia), 76(6). [online] Available from: https://magazines.gorky.media/nlo/2005/6/film-ironiya-sudby-ot-ritualov-solidarnosti-k-poetike-izmenennogo-soznaniya.html [Accessed 7 November 2020].

- 25.Prokhorov 2017, 120.

- 26.Los Angeles Times Obituaries. 30 November 2015. Eldar Ryazanov dies at 88; Russian filmmaker satirized life in Soviet era. [online]. Available from: https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-eldar-ryazanov-20151201-story.html [Accessed 7 November 2020].

- 27.Milic, S., 2006. Situation models in cinema: Diegetic worlds and viewer perspectives. Thesis (Ph.D.), The University of Iowa, 219.

- 28.Yurchak 2013 A, 8.

- 29.Bobrova, E. & Erkovich, V., 2015. This New Year, raise a glass to Ryazanov. In Russia Beyond The Headlines insert, Washington Post. [online]. Available from: https://issuu.com/rbth/docs/2015_12_2_wp_all, 4 [Accessed 7 November 2020].

- 30.Prokhorov 2017, 121.

- 31.Prokhorov 2017, ibid.

- 32.Humphrey 2005, 43.

- 33.Yurchak 2013 B, 37.

- 34.Urban 2008, 18.

- 35.Yurchak 2013 B, 75.

- 36.Yurchak, A., 2013 C. Dead Irony: Necroaesthetics, “Stiob,’’ and the Anekdot. In Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 238–281; 250.

- 37.Yurchak 2013 C, 250.

- 38.Hirt, S., 2012. The Post-Socialist City. In Iron Curtains. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 34–59; 37.

- 39.Prokhorov 2017, 119.

- 40.Attwood 2010, 195.

- 41.Varga-Harris C., 2017. Liminal Places: Corridors, Courtyards, and Reviving Socialist Society. In Stories of House and Home. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 106–135; 108.

- 42.Prokhorov 2017, 111.

- 43.Humphrey 2005, 48.

Leave a Comment