We met Czech actor Jan Kačer in Prague to speak to him about his career, the political climate in the 1960s, and his collaboration with Evald Schorm.

Let’s start with your time at DAMU: did you already have connections to FAMU and the film world at the time when you were a student there? What was the political atmosphere like?

Well, we were all fellow students, in fact roughly of the same age – born around 1935, 1936, 1937. It was an odd time as the war had been over for quite some time. It was calm, and yet the world order seemed unstable. The consensus was that the Russians had won, of course: the state did everything to downplay any share of the West in the victory, which is important to stress. So at this odd time, coming from a small town and all, I wanted to become a doctor, I had no ambition in the arts whatsoever. I was sick quite often myself and so to me, medicine was like magic in the real world, a form of totality, a calling even. In a small town, being a doctor was like being God – you could save people’s lives. But back then, you didn’t get into school by taking an exam. Someone had to recommend you for one reason or another. I was attending a regular school in my hometown, and then I switched to a high school in Pardubice because I wanted to continue my studies. But I didn’t have good credentials: my father, who used to be an engineer with a small factory, had long been dead, and so there was nobody to recommend me. Anyway people were afraid of the regime, and here I was without a chance of going to university. Then one of my uncles told my mom that I should try art school – I did have some interest for painting and making stuff out of clay – and art schools did have entry exams. Finally, I got accepted to a ceramics school in Bechyně, I was 14-and-a-half at the time: the principal was this high school professor who wasn’t able to teach in Prague for political reasons. He recognized I meant business and took me in against the rules. There were some people in the school administration who raised their concerns, but he said that I’d already been in and that was that.

Bechyně is beautiful. We were a hundred students and it was really a school for talented people. Not in some genius sense, but compared to the ordinary man we were fairly gifted: we could paint, we could mold stuff. It was something in between a high school and a university, and the teachers who taught there were people who’d been shelved away by the regime. That was in 1951, a hostile time: Socialism was beginning to unfold, so everybody’s the same, chaos, people being locked away. Still, I was at Bechyně until 1955, and I was free to do whatever I wanted. Dancing, writing, acting. We were young and didn’t know what else to do, so we traveled around local villages and staged plays. I had no professional experience in theater and probably didn’t know squat, but tried out whatever they would stage. So without really being aware of it, I was acquiring organizational and practical skills. I originally wanted to go to UMPRUM [Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague] – Bechyně was an art school after all. And then a professor – also a skeptical of the regime – approached me and told me that if I thought I were better at theater than at painting I should try acting: “Even if you’re second-best at drawing here, you’ll be number 15 in Prague.” Of course, until then, I had taken theater as a joke, I probably wasn’t even aware of the fact that you could study theater. My professor lent me some of Stanislavski’s books, and it really seemed clear to me.

So I enrolled at DAMU [theater faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague] – which, at the time, in 1955, like FAMU [film faculty of the A.P.A. in Prague] – was a top-notch school. Still, it wasn’t like today. Today, if you’re talented you can choose to go wherever you want, but then FAMU and DAMU were safe havens, a paradise where you could learn how things really were – without the Leninist and Marxist bullshit. At AMU [A.P.A. in Prague], amid this totalitarian confusion, they taught you about fantasy, and I knew that. I knew that it interested me and that I wanted to do it. I enrolled for directing because it seemed far more familiar than just studying acting.

I remember coming to Prague to enroll. The night before the exam, my aunt took me to the theater although she didn’t believe one second that I’d be accepted to a good school: she had no children, and to her we were good-for-nothing rascals. I was thrilled by the play, and then the next day, well, I might be embellishing this, but doing the exams for directing was a real problem. If you want to test a violinist, you let him play on the violin, if you want to test a pianist, you let him play on the piano. But what’s a director? One precondition was that you had to be 22 years, while I was only 18. The first step was a written examination, a sort of intelligence test, and then there was an array of questions around 100, of which 90 were about art and art history. Coming from an art school, I got 92 points, beating all these guys who were more educated than me and who had finished high school but ended up with 60 percent. Entirely fortuitous. Well, when I arrived at the exam, it was the actors I had seen the night before on stage who were on the commission, apparently they all knew about my exam, and they asked what my most memorable experience in theater had been. So I told them about the night before, about the only real theater performance I’d ever seen, and I guess they thought to themselves they’d finally found themselves a smart kid. I was accepted and started going to classes straight away. Coming from a small town, Prague was truly astonishing. This was a free city, something was happening here.

I took school very seriously. There were a lot of people at AMU whom I admired, and actors with whom I had great relationships, professionals whom I would otherwise never have met. And then there was FAMU, the sister school. We hung out a lot with FAMU students, and yet they were in a better situation because they had access to foreign films, whereas we had never seen a theater from abroad perform. The FAMU students were the aristocracy, and they were well aware of it and often arrogant. All these film people that you know about were our peers, but they were distant peers nevertheless. I remember saying that I wouldn’t ever do film because it’s disgusting and the people suck. After some time at DAMU, I got fed up with the theater they did in Prague and moved to Ostrava to form a theater group with 12 other people. We thought Ostrava was a city that lacked culture, whereas in Prague it would be impossible to assert ourselves. Instead of hanging on to the world of TV and film, we went out into the wild, and it worked out. A year or so later we were already given a stage at the house of culture, and at 22 I was establishing myself as an actor. We did everything: organization, planning, dramaturgy. That’s when I started travelling back to Prague regularly to see what the opportunities were. After a while, I grew closer to some FAMU kids, too. There was already a consensus, a common thought that saw its culmination and violent end in 1968. We all wanted it, all the good people from theater and film. Sure, we all had our takes on the world and life, but the foundation was the same.

Meanwhile, I also found myself affiliated to a small TV station that was formed in Ostrava: I was hired to film local curiosities in Opava. Musicians, artisans, feasts etc. But it really got to me: those reports were transmitted live, so I was constantly struggling to figure out what to say. One time, there was this Libra guy, a stuck-up architect who was telling people how to furnish their apartments. That was in the 1960s, so we’re talking about really progressive material. We made a last test, and I went through the whole thing with him: “Good day, Mr. architect…,” and then I just kept stumbling and mumbling. I had a feeling of complete failure. When I went to work back at the theater the next day, I was told some people from Barrandov had called me: Kadár and Klos [János Kadár and Elmar Klos]. I didn’t want to have anything to do with Barrandov, but in the end they won. They were preparing to shoot Smrt si řiká Engelche [Death Is Called Engelchen], based on a popular novel, and they wanted somebody unknown for the role of the Partisan, and that unknown somebody turned out to be me. They’d seen me on TV promenading through Opavian filming local curiosities, and that’s what they went for. They invited me, I refused, and yet I ended up doing the project. It was a 2-part film which was shot on 130 days with 45 meters of material being shot every day. I was driving from Ostrava to Prague, from Prague to Liberec – the setting was 45 kms from Ostrava, but since the DoP’s house was in Liberec, we shot a lot there – so that I left hundreds of kms behind over the course of the shooting. On top of that, my children were born during the shooting: I despised the project. But at the same time, I learned a lot about film. I learned how to view myself, why they chose shot X from the 10 shots they had shot. It was a valuable learning experience: I was learning how to shoot while on set. Kadár and Klos – who did have an argument or two during our odyssey – were great directors, and so in spite of the fact that I heard a lot of opinions on the film, the project got me interested in filmmaking. Moreover, the film was successful, more so than I was expecting, it even got me the first and only award I have ever received – 5000 CZK from the minister of defense one day before I was drafted! And the film won a prize in Moscow, too, which is another important thing to mention, as I traveled to Russia for the festival and started meeting different people from the film world.

When you start playing in a film that attracts attention, you can’t pass a theater where there are posters with your face all over it and pretend you don’t have anything to do with it. You’ve become part of the film world and you even start rooting for it, there’s really nothing you can do about it. One day, I got a package from Máša and Schorm [Antonín Máša and Evald Schorm] with a script in it, and note that during that time, there was no explicit dissent, there was no systematic resistance against the regime yet. There were plenty of people who had problems with the regime because of personal experience, perhaps because they had been locked up, but overall it was successful. Prices were on the wane, and the consensus was still that the Russians had liberated us. It seemed peaceful and warm and nice. I myself can’t say that I was having a hard time. When I heard about the project, I dove into it immediately. The protagonist of the story dies on a huge iron wasteyard which was right in front of my place.

You could say that Ostrava was a bit crude and adventurous: Prague was urban, whereas Ostrava still had fires flaring up here and there, trams driving in the middle of the street with their glaring lights, and a thousand bars with each being different. It was free, rough, a bit like Chicago I guess. So I read the script and it struck me that the story reminded me of my own fate. Not that I was like the protagonist, but I recognized some nuances. I also thought I could change the world and sacrifice myself and all that non-sense. It was a very critical perspective of our world, and that really engaged me. It looked like a friendly film about a partisan who fought with the Russians for the liberation of the world, a heroic story, but then we all burnt down in the end: a critical film. I called these guys back immediately – I had no idea who they were, hadn’t seen any of Schorm’s films. At the time, Peter Brooks was here for the first time with King Lear in the Stavovské divadlo [theatre in Prague], and of course everybody was there. Try to imagine what that meant to us: an outstanding English ensemble performing in Prague at a time when all that was being played was Russian. Well, at that play, during the break, I saw Schorm for the first time, I recognized him immediately because I had heard what he looked like: a 2-meter guy with a beret. To me, the encounter was truly life-changing: it’s from this point that I consider myself to be part of the film world. Sorm, and Masa were highly observant characters, and I connected well with them. I’m not saying that I regret doing what I did before that, but for this project I was really excited. It’s also there that I started having a broader picture of things, this social consciousness. Untilt Evald [Schorm] died, we did everything together.

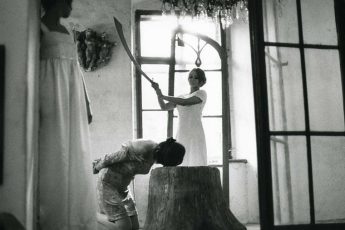

Take the final scene from Odvaha [Courage for Every Day] where I’m beaten up: the sentenced, ostracized outsider. When I got up on my feet, Evald stared at me from behind the camera and told me: “Smile, Honza, smile!” I immediately knew what it is he wanted, he didn’t want to make another film is solely obsessed with our misery. He wanted us to look towards the future, to think about what lies ahead.

How was working with Evald Schorm compared to collaborating with people from the older generation, for instance Elmar Klos? Was there a difference in the things they addressed and cared about?

Klos was a professor. He was a great guy, very educated, and knew how to organise things. A classical filmmaker, even if fellow helmers claimed he didn’t know his stuff. [Ján] Kadár on the other hand was insane, a crazy filmmaker, and that’s why Klos and him would always argue. But it was classical filmmaking all the same. There were around a 30s of these “classical” filmmakers that are often forgotten: [Václav] Gajer, [Jiří] Krejčík, [Jiří] Weiss etc., who always worked with big crews, whereas the young guys wanted to keep their crews small.

The young guys were interested in other things than just the filmmaking process and getting a few nice shots: they wanted to convey an idea. And they were happy to find people who thought the same as way they did, we were all friends: they had a different understanding of what it means to make something “collaboratively”. That’s the juncture when theater and film emerged, perhaps film even a few notches more. They were replacing the state ideology, this opaque party line which tried to dictate how you should live, but which was dissolving because in truth, noone was taking it seriously. Film and theater were the only platforms for interesting and meaningful standpoints and philosophical ideas. In many cases, film was in fact harmful to theater because all considerations related to style and interpretation were constantly being disrupted by this pressing imperative of expressing political dissent. Surely the yearning for freedom can be powerful in art, but in this case “art” was being subjected to internal drives of different nature. As for film, all the work we did after this point was meaningful – I collaborated on a great movie based on a Milan Kundera novel with Hynek Bočan [Nikdo se nebude smát]. I have no idea how FAMU [film faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague] is doing right now, but as you know, Kundera was himself teaching at FAMU back then. Kundera was a special phenomenon. Originally from Brno, he taught at HAMU [music faculty of the A.P.A. in Prague] – an outstanding specialist on Janáček [Leoš J., Czech composer] – and was a man of impressive stature and looks: 2 metres high, dark hair. He taught comparative literature at FAMU and was highly popular, all the students admired him.

Did you have a chance to attend one of Kundera’s courses?

Yes, but most important of all I got interested in him when I played his role. Anyway he was so distinctive that he was all over the place. It’s hard to pinpoint where this “New Wave” originated – I suppose many people think [Otakar] Vávra [director, former professor at FAMU] played a big part in it – but if I were to name one figure who engendered social, political and artistic awareness among filmmakers I’d chose Kundera. On top of everything else – his talents, knowledge etc.-, he was just very different. At DAMU there was one Beneš [?] guy teaching Marxism – I never went to listen to that babbling – whereas the FAMU kids were talking about the French New Wave.

But to get back to Evald [Schorm]: he was a guy who knew everything. He was older than the rest of us, too, born in 1931, so Věra Chytilová [born 1929] was the oldest and he came right after that. He was a dilettante in the good sense: self-taught. He knew everything which you could get a hold of, every book that was being published was at his place, and top of that he read every newspaper. In short, he knew everything about everything. I knew Evald for 20 years, and noone from the film world has ever asked me about him. When I met him at the theater for the first time, that one night [see first part of interview] , he said that he had seen me at the theater many times. Obviously I was fascinated by his knowledge, especially when we started to make “political” films together. At one point, he even suggested that I should take courses in documentary filmmaking at FAMU to get a better grip of cinema. We cared about each other. We wanted each other to constantly improve, to reach our limits. We didn’t only want to be critical, we also wanted to know everything.

You have to remember that I was still living in Ostrava at the time, a city which had a certain ideological connotation. They allowed us to premiere Courage for Every Day behind closed doors so that we wouldn’t harm the workers and miners, and these idiots closed the doors and wrote an invitation to the head of the youth association for the screening of a “highly suspicious” film. In short, the people who attended the screening were preparing to “correct it”. The film was screened, and in defiance of the shocked party representatives, the workers pronounced their fascination. So this film which screened at festivals around the world was banned at home, and I remember reading ridiculously conflicting reviews. In Czechoslovakia, they said that my role was not believable and that “workers like this didn’t exist”, whereas a French reviewer was glad that someone had finally captured the soul of the worker, pronouncing that this was the way that future worker would look! The film stirred controversy, but it was also highly successful, and from that point on – well, I guess always – I only did the films I wanted to do, turning out a number of interesting projects on the way. I had a couple of offers from Russia, but never considered accepting them.

What was your approach to the script of “The Seventh Day, the Seventh Night”? Did you talk a lot about your role prior to the shooting?

It all happened very fast. The film was shot quickly and without any superfluous discussions. There was complete chaos: noone even approved the project in the form that we had developed. But that’s the way it worked with Evald: “Hey Honza, I have this new thing”, and when I read it I knew exactly that it was written quickly. Evald never edited the film – it was taken away from him before he could finish the piece, so noone really knows what it should have looked like. I prepared for the role on my own a lot – when you have some experience and know what the director is going for, you know how to approach your it. I chose a white shirt and a sweater one or two sizes too small so that my bare arms showed. I wanted to be a certain type of teacher, I was going for the nuances. But it was predictable that it wouldn’t be screened – it’s a portrayal of the occupation. It was funny: we shot many people who had no idea what the film would look like. If they did, they would have never approved of it, but that’s how we did it. Evald depicted this super-loyal Bolshevik as the biggest asshole in the film, and the guy knew it, I guess: he was trying to make something up with his role.

You had a different take on “Courage for Every Day” than the novel suggested?

Well, it’s all related. Imagine this happened to you: you have an internal understanding of how things should go, and then you see yourself on camera 10, 20, 30 times from all sides and all angles, and you start thinking that you might have just imagined certain things. The camera sees everything. You might die a hundred times on stage, but the camera sees everything, there’s that technical scrutiny: everything you say has to be a hundred times more truthful. So in Camus’ story [The Outsider], there’s the guy looking after his dying mother, awaiting his sorrow and all the things related to the death of a close person, and suddenly he realizes that he’s interested in the flies that are soaring around, in the way he’s sitting there, destroyed without showing it. It was a primer in acting – one of the many books that teach you how to act. And it’s not just the technical side that I’m talking about: there are a lot of great actors who never realize this, they just act the way that you act in theater. I’m not trying to define or reduce anything to a formula, but they don’t realize that acting on film is a life experience. You can’t be agitated when you act, which is something I learned in many different ways. I had heard about great American actors making notes about everything, and I also knew about the way Czech actors worked, for instance [Václav] Lohniský, a clown who worked on ten projects at once. There’s this anecdote where Lohniský didn’t know where his hat is, so everyone on set had everyone had to look for it, but 15 minutes later they realized that the hat was part of a completely different film. This is truly representative of the way actors acted over here, whereas professional actors have an understanding how the shots will work, what lens will be used in this or that shot and so on. So I said to myself “I can also do that!” On the one hand, I began being picky about projects, on the other hand I started approaching film differently.

It all started with The Valley of the Bees [František Vláčil], a project for which I had to study Latin, learn how to ride a horse and keep a diet. On top of that, we traveled to Germany with another film during pre-production, so for once in my life I was staying at a fancy hotel, being offered fancy food on a daily basis, and I had to feast to lose weight! I remember people asking me whether I was unhappy with the screening because I didn’t eat or drink anything. But these were sacrifices which payed off great. I understood that it was doable if you accepted the fact that you’d have to live with this film for half a year. It’s such sacrifices that helped me understand the broader picture of things: at film clubs we’d talk of meaningful films and about how they were connected to the reality outside cinema. Film and theatre were morphing into opposition platforms for contemplation and philosophizing and finding a meaning in the world. And the images! When I peruse these works today, after all this change in the world, I realize how great the cinematographers and camera people were that we worked together with. Or take Barrandov in the context of this gray, sordid life: an island of escape.

Once, there was this festival of Czech film in the States where they screened four films in which I had the main part. They were writing “where’s Marlon Brando going with this?,” because Marlon Brando is a pretty good actor, but he lacks intellectualism. I laughed at these comments, but I also realized that since our works were traveling around the world, I – coming from a small village in Czechoslovakia – suddenly started competing with Brando, Mastroianni, and all these people who were doing the same thing as me in their countries. It makes you feel like you have a certain responsibility towards your country, like you can extend the borders of the small world you live in. I don’t like competing, and I’d certainly never take part in a competition where the aim is to determine who’s best, but this chance to expose your own culture – especially in the light of dissent and awareness-, this was something which engaged me. You could compare it to sports, obviously: [Petra] Kvitová [Czech tennis player], too, competes on a global level because she’s good enough, and that communicates a feeling of equality. We were a small nation occupied by Russia, people had no self-confidence, and here we started bringing home awards from renowned, international, and foreign film festivals. It was beautiful.

What role did film criticism play in the development of the new film culture? In France in particular the influence of critique was very visible. Was there room for serious criticism in Czechoslovakia?

There were some film magazines: Filmova Doba, Kino, so there were platforms for film criticism. Maybe the quality was not the same, but these publications proved that people cared about film culture. There was interest. Remember that the regime had an ambivalent stance towards opposition films: surely, they knew that they expressed dissent, but they didn’t prevent such films from being made. It was difficult, but possible, they were financing their own criticism. Imagine that happened today. Of course, you can’t transfer the reality one to one, but there is something about it. This was something which the regime approached correctly.

It sounds like Schorm treated his actors without directorial “condescension”. Was it the same with other directors, say Václav Vorlíček?

Vorlíček was an artisan. You came to set and were pumped to play agent V4C [Kačer played the main role in The End of Agent W4C], so you learned what you needed to know for your role and delivered it. I never talked to him about anything not directly related to work, I felt like he was hostile, but I suppose that’s my personal impression. It’s like ordering coal and getting coal [Czech proverb], whereas with our peers it’s almost wrong to speak of collaboration. Everything was created spontaneously based on the experience of all the people involved. We were all equal, brothers you could say.

Of course, it was tough – working with [František] Vláčil was particularly tiring because he was a relentless perfectionist. This one time, during the The Valley of the Bees shooting in Poland, we were working on a difficult scene with horses: we had to postpone the shooting several times because we couldn’t get horses from Poland – they thought a Czech horse would be scared of the water – and when we finally did, it was insanely taxing because Franta wanted the left hoofs of the horse to be on sand, and the right hoofs to lightly splash the water. Well, it turned out that the Polish horse they got was just as scared as the Czech horses. Through some miracle it did work out in the end, and we got this beautiful, long shot just the way he had imagined. We went to the editing room, plaudits, cheers, applause, all proud of what we had achieved, and when we turned to Franta he said: “It’s too long, I’m not going to use it.” I could have killed him. But it was great all the same. I don’t know how these guys did it – Franta didn’t even say much on set, and yet you had the feeling that you knew exactly what you were supposed to do. I remember we were shooting a long sequence and I asked him how he wanted it, and he told me: “You’re the actor, Honza, how do you want it?” It puts a lot of pressure on you, but it’s also inspiring.

Who watched films from the Czech New Wave? Were ordinary citizens interested in accessing this platform of opposition?

There was a poetry club magazine at the time which had a circulation of 300 000. Imagine a publication about poetry having 300 000 readers! The magazine came with a disk with recordings of poems read by contemporary actors, and people finished this stuff in two days. There was an odd, collective yearning for culture at the time, you could almost say it was expected of you to care about art.

Again – it’s not that life was unbearable back then. Ordinary people lived pretty well, I think that a lot of people would have to admit that they had it better than today: you payed your 130 crowns for your apartment, noone was able to kick you out, and everyone had a house on the countryside where they could spend their weekends. Basically, if you had no objections to their style of governance, you were fine. What the regime expected from its citizens was silence – no resistance-, but at some point things starting going down. When there’s no innovation, things start getting worse. Suddenly there was a lack of “vitamin”, a lack of interesting experiences. Life is not just about material things and gluttonizing, and that’s how this strong base for art was born. In every household around the country – whether it was Ostrava, Opava, or Prague -, you’d find the same books – that’s true, and certainly sad -, but they had them everywhere all the same. And when an interesting film found itself into country, say from the French New Wave, everyone knew it. People don’t talk about this a great deal, but there were literary newspapers with 500 000 readers. At the time when I did TV films, you’d be on TV on Saturday, and by Monday you were famous. Television wasn’t as commercial as today, it was a novice’s TV, they’d even televise plays. Today there’s so much material and so much chaos that people don’t pay attention to you anymore, but then art really had an impact on society.

When I played in the theater, there were 200 people who wanted to talk to me after our shows because they felt like they shared something with you. If I went to the same theaters today – being this much experienced – noone would come because there’s a different atmosphere. I think that the Velvet Revolution took on the form that it did because of culture, it was a revolution where not a single vulgarity was uttered. I was actually asked to announce my candidature for parliament by some young people who knew my work, and I got 167 000 votes! I had the second-most votes in the entire parliament. This was the moment in our history when our cultural foundation in society really payed off. After that real “politics” started: intrigues, corruption, thieveries etc. I think nowadays people don’t understand why there are so many theaters in Prague or why we have two operas. It’s because that’s what people wanted. Evald’s films were not allowed to screen in regular cinema, they were non-classical halls which were adjusted for screening films, and yet everyone saw them. When I’m asked today if Evald’s films should still be screened, I don’t really know what to say. First of all, they’re monochromatic, and secondly they’re part of the social and political atmosphere of the time. So I do feel like people might be disappointed.

What’s your impression of post-89 cinema in Czech Republic?

You have to be careful with such questions. Every era has its heroes, and no filmmaker bases his aesthetics and style on anything but himself. Every filmmaker speaks about his own problems, his own passions, and his own girls. I have nothing to do with this and can’t really criticize it: why should an old geezer like myself judge what to make of current cinematic trends? What I can say is this: back in the day, filmmakers concentrated their strengths on writing a good script to 90 percent – good as in truthful -, and 10 percent on finding a producer who’s ready to approve the project. Nowadays, finding a producer takes up 90 percent of your energy, and 10 percent are left to concentrate on your film, while casting is decided according to popularity. I have nothing against [Bolek] Polívka and [Anna] Geislerová who are everywhere, because our young directros know that these are the people that people will go to see in the cinema. Back in the day, [Jana] Brejchová was a huge star who played a lot with Evald, and yet noone ever thought of casting her for ratings. People went to see Sorm’s films because they were his films and because there was an idea behind them. I myself was also everywhere and never became a star.

Thank You for your time.

Leave a Comment