Our decision to turn to Hungary for our regional focus in 2013 was in large part informed by the difficult state of cinema in the country. This difficulty is twofold. Firstly, the government of prime minister Viktor Orban, who came to power with his center-right party Fidesz in 2010, has taken major steps to restructure the national film fund, a step which has worried filmmakers across Europe. Secondly, Fidesz’s ambitions of reshaping Hungary have never been restricted to or focused on the arts. Rather, as György Pálfi noted in an interview with our journal, the (in this case undemocratic) film fund is a befitting representation of how a government runs its country (which, assumedly, demands public reflection from artists and intellectuals alike). While this last observation has recurred in editorials for our publication, it is problematic in view of Pálfi’s claim, made in the same interview, that the previous film financing system was just as undemocratic as the current one. This in itself is not as unplausible as what follows: if the national film fund does indeed represent a regime’s style of governance, and there is no visible improvement in the former’s pluralism, one can conclude that Hungary has not seen the anti-democratic shift that observers have recognized.

Needless to say, post-1989 political misery hasn’t started in 2010. Leftist governments in Hungary were notorious for their corruption, misappropriation, and (related) economical inefficiency. Still, qualifying Fidesz’s measures seems perilous to say the least. In recent interviews with Hungarian directors, rather than open disapproval, we have witnessed circumspect reservationn, explicit relativization, and outright disinterest apropos addressing political problems. So far, our favored explanation has been this: financial dependence from state funds motivates self-censorship both on and off screen. In this month’s issue, Czech New Wave actor Jan Kačer (Courage for Every Day, The Valley of the Bees), himself a vocal critic of the Czechoslovak and Soviet regimes, points to the silent tolerance of the censorship apparatus in post-war Czechoslovakia: the regime, he thinks, was ready to accept dissent (if within certain boundaries). This, one could say, is taking the argument one level further. In 1960, too, in fact more so than today, filmmakers were dependent on state funds. Still, socially and politically critical films were abundant. The difficult state of political cinema in many Eastern European countries says a lot about today’s political situation. Are regimes ready to face criticism, and are filmmakers doing enough to exact that readiness?

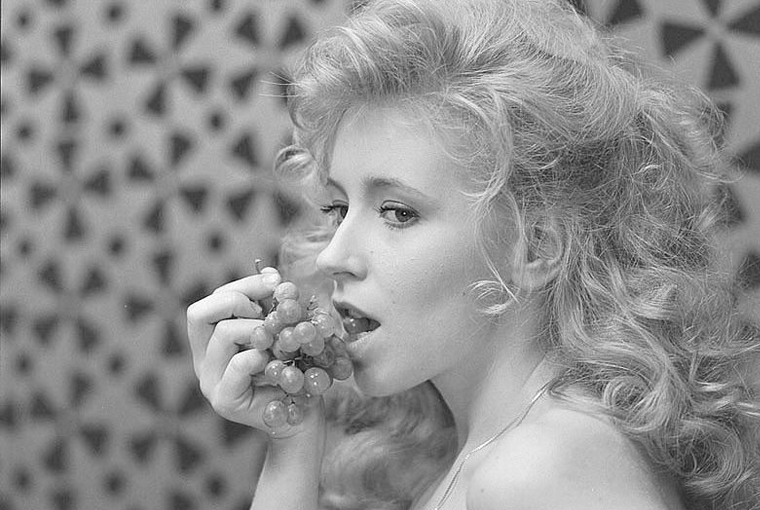

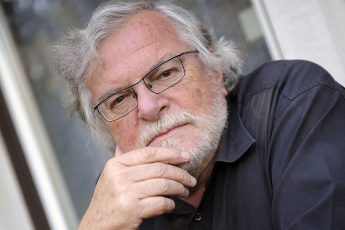

In our interview with Kačer, the actor speaks about his formation, the political climate in the 1960s, and Czech cinema. We also discuss The Seventh Day, the Eight Night, starring Kačer, in which Konstanty Kuzma sees a failed allegory of the Prague Spring. Meanwhile, our Hungarian focus continues. Patricia Bass addresses the unimaginative fetishisation of wickedness in János Szász’s Opium: Diary of a Madwoman, while Kuzma saw Ildikó Enyedi’s My Twentieth Century, which offers a wary account of modernity.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment