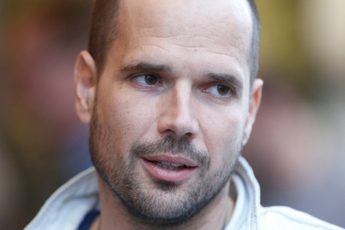

Razvan Radulescu, 42 years-old, is one of the leading figures of the Romanian New Wave. He wrote the scripts for films such as Cristi Puiu’s “Stuff and Dough” and “The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu”, Tudor Giurgiu’s “Lovesick”, Radu Muntean’s “The Paper Will Be Blue”, “Boogie” and “Tuesday after Christmas”, Constantin Popescu’s “Principles of Life”, among others. Furthermore, he was a script consultant for Cristian Mungiu’s “4 months, 3 weeks and 2 days”, and co-directed “First of all, Felicia” along with Melissa De Raaf.

How did you become a screenwriter ?

I studied music, then I studied language and literature, and I have been writing since I was a teenager. I used to write short stories… By the time I wrote my first script, my first novel had not even been published. So it was more like a mix of cultural challenge and social challenge. At the time, Cristi Puiu and I were very close. He did not have any perspective of making a film in Romania, but we finally managed to ensure the right conditions to make it there. This means that the CNC was put in place, the law was adjusted, and the first public contest for Kodak was organized. We started to discuss the film together, the idea was clear… Writing a script appears to be a challenge of its own. I had contact with a consultant when I was working in a magazine to make a living at the time, and he told me there was a special software for writing scripts. I asked myself what was the big deal about it, but when I saw it, I thought : it’s brilliant – a software that limits you to only write what you see and what you hear. This is how I started to write scripts. I was very happy with this first film (Stuff and Dough), and I think it still makes sense nowadays. It doesn’t get old.

You started with a feature film which is quite rare among filmmakers. People generally start with short films…

Sure. It’s normal that in a certain system one thinks there’s a progression from a short film to a feature film. But I don’t agree. It also happens in music. In music school, in the first and second year you learn how to play baroque music, then romantic music, and last, contemporary. But romantic music is actually easier to play than baroque music. In terms of screenwriting I didn’t feel compelled to obey to this system.

“Stuff and Dough” is a road movie. Did you approach it as such when you were writing the script?

Yes, it was very clear. We were aware of the fact that the movie should contain a confrontation between bad guys and good guys. And that it should involve a chase, a gas station, someone being stopped by the police… And all this happens on screen. We obeyed all the structural points. Why not? It makes sense.

And after that you continued working with Cristi Puiu, in Lucian Pintilie’s “Niki and Flo”…

Puiu and I continued to write, because after making this first movie, making a second wasn’t so obvious. The thing is, after a long pause a Romanian movie was finally in Cannes again – Stuff and Dough. It didn’t impress anyone, so a second film wasn’t viable so fast. So we started this project together with Lucian Pintilie. That was a very good screenwriting experience. I’m very happy and very proud of the script, because it was my most disciplined experience of writing. I’m not normally like that. But as we were two people writing and we had to meet up with regularity, I had to be disciplined, and I think the result as a script was very good. The film itself is disappointing. I think that the tone of the film is very different from the tone of the script. The reasons why I liked the script are very different from the reasons why Pintilie liked it and why he wanted to shoot it.

Do you think that happened because he’s from a different generation?

No, I think it’s just a different temper. For him, the reasons behind the main character were payback and anger, he’s a very vengeful man. And this wasn’t mine or Cristi’s intention. We looked at our characters with comprehension and love. Both at Niki and Flo. No matter how stupid they look sometimes. Me and Cristi could be understanding and harsh, depending on the moment. But Pintilie was different. He wanted to take revenge for all the problems of Romania.

After that, you worked on two films that were very successful, “The Paper Will Be Blue” (by Radu Muntean) and “The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu” (by Cristi Puiu). What were your expectations for the success of these films?

First came The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu, and no, I didn’t expect it to be such a succesful movie. Between Niki and Flo and Lăzărescu, Cristi and I had written something different. We could communicate very well back then. But though most of the work was done, it never came to life properly. Then came Lăzărescu, a film about how to die. I expected very little, and then people started to talk about the New Wave of Romanian cinema. But I don’t believe in waves and generations. I believe in people with different interests that have a common loath towards the older generation and a certain desire to be seen more precisely.

Do you think the Romanian critics misunderstood the film in the beginning? Some saw it as a critique of Romania’s health care system.

Not all of them. There are two or three of them from the younger generation that wrote early critiques that were very witty. They understood the movie and wrote very accurately. Those who saw the film mainly as a critique to the medical system… they found it easier. The critics abroad probably watched the film and couldn’t relate it to their domestic health systems, so they reached the real dimension of the film, in which a man is dying.

Does “The Paper Will Be Blue” reflect your own experiences during the revolution?

It tells more about the gradual shame my generation and I had year after year when we saw images of then. The enthusiasm we had then… More and more your illusions dissolve. When you understand why you lost your illusions, those moments of mindless joy and blind hope that are seen in those video documents of the time make you feel ashamed and also melancholic. You think « how could I be so stupid », but at the same time it was impossible to be different. I was young and stupid, and so were the others. This was the way to be: pathetic, with a trembling voice, with enormous things to hope and wish for, and very prone to be disappointed. In this film, people are imagining their tomorrow at that moment. They have burning eyes and trembling voices. They’re oor people. I don’t think it’s a film about the Romanian revolution, it’s about all major shifts. We wanted to make a film about the people, not about a generic revolution. I don’t think that exists, because every person participating in a revolution sees the future in a very different way. And the more you go towards the future, the more future disappoints you. Future reveals another revolution – that’s what makes the future so mediocre and so banal.

You also worked on Muntean’s two subsequent projects, “Boogie” and “Tuesday after Christmas”, which are more intimate films. To what extent do they speak about your own experiences and to what extent are they “technical” works?

Yes, the films do become more intimate over time… Technique comes from experience, and experience comes from the things you do. I can say without being arrogant that I have quite a large experience because I wrote many scripts, and I also have a good technique because I have a lot of experience. But after a while technique doesn’t matter that much. Technique was never an issue, because you can’t do that much with technique only. It’s just a way of becoming proficient; underlining what you already know and what you want to do. I would be able to write a story that wasn’t about experiences and that would address certain personal issues such as anguish. It’s always about me, what they, the audience can share with me, and what I can share with them. A certain view on this anguish…

How do you see Bogdan, the main character from “Boogie”? Is he in a crisis,because he’s turning thirty and he’s seeing his life as something too solid? Do you think it’s an experience every man shares?

Talking about how we were, what we aimed for, we all feel the way Bogdan does at some point. Of course the feeling of being trapped in the future you build for yourself is something for all of us. Every man has a role to play. The society shown is a bit like the societies all around the world: there’s pressure from both sides. And the question is how you can cope with it. How you cope with irresponsibility. The goodbye to your bachelor’s life is slow. Not so much when you only have a child, but when you have a child, and a job, and a second child coming, you finally have to say goodbye. But it’s a bit cruel, it’s too much. I’ve never been like Boogie, but I would consider imitating his behaviour if I had to. If I had to put it short, the sentence would be: we never materialize in our lives.

Do you think Paul from “Tuesday After Christmas” is an evolution of Bogdan – Boogie? Do you think Bogdan would become Paul, with a growing daughter and a mistress?

Sure, you can see it that way. If Costi from The Paper Will Be Blue hadn’t died, he would have become Boogie, and if Boogie hadn’t had a second child, he would’ve become Paul. There’s some continuity in the characters. Costi would have taken any responsibility, Boogie would have taken the responsibility eventually. And Paul, after having taken the responsibility, he would have understood all the wrong things he did, and he would have liked to delegate the responsibilities. He is probably the least forgivable of the three. I don’t know where I would position myself, what is good or bad.

How was it working on Tudor Giurgiu’s Lovesick, and as a script consultant on 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days?

For Giurgiu’s script, I mostly made changes in the strutcture since it was an adaptation of a book. I had the opportunity to discsus the book with it author which was very helpful. We had to choose among a number of voices and insights the novel had – it was not a very cinematographic novel. Then we had to invent the way of speaking and polish the dialogues.

For Mungiu’s film, I was shown a draft which was quite close to the film, and we had a discussion about it. There were many parts that didn’t work at all. We had to start collaborating on the film. I would have never been attracted to the film just by the fait divers. Nor by the woman who has an abortion and then gets a friend to get rid of the foetus in a garbage bin. So there was the character of the “doctor”, Mr Bebe, who has no concern for any human being and whom I wanted to highlight. All the part of getting rid of the baby should be diminished to a minimum. For me, this is not a story about guilt. It is a story about abuse, and about the way you tolerate it. The communist system constantly put you in a situation of being abused and feeling guilty for it. When you are abused again and again, you feel grateful once it’s over! The whole relation between Gabita, who has the abortion, and Otilia, her friend, is about abuse. I think this feeling is best represented in the birthday sequence, at Otilia’s boyfriend’s place, when she has to turn towards her own life, but she is completely connected to what’s happening to that person who abused her. So she cannot stay there.

How was it like to direct your own movie, “First of all, Felicia”?

I worked with Melissa DeRaaf who is an excellent writer; we developed the idea and the script together. She had very good insights about what could be better, what could go wrong; and most of the time she was right. When it comes to directing, and directing together, she also had good visual insights. But I prefer to talk about my own experiences. We both wanted to tell this story, to talk about time, how real time can be. Dramaturgical time is different from real time: the time you experience and then is layered in your memory is all squeezed in dramaturgy. All the elements that contribute to give you the sense of time are heightened markers of things.

Do you think your experience as an expatriate is shown in the film?

The theme of being a guest in your own house, a tourist in your own house, is quite alienating there. You have to make efforts to belong to your own home.

Is Felicia’s mother invading her space? How do you see the mother?

I think the mother is at an age where she can’t realize she is invading Felicia’s life. People at this age have very little capacity for self-reflexion. This is how they survived the communist times. I think she is trying to recuperate her daughter’s affection with what she has at hand: advising her about everything. Felicia’s mother is trespassing her own limits since her daughter is a guest. I believe Felicia would also like to recuperate something, but in another way, because she is from a different generation.

What do you think about “Principles of Life” and your collaboration with Constantin Popescu?

Constantin Popescu was just a person I knew. We never had a very close relationship. He was not the director to whom the film was meant to be given, initially it was Radu Jude. Radu and I worked out the whole structure of the film together. Then we pitched it several times, but when it failed the first CNC contest, Jude dropped the project. Constantin Popescu was very enthusiastic about the script and wanted to make it. It’s a movie I see with pleasure.

And what are your next projects?

Ahhh…

Thanks for your time.

Leave a Comment