There’s a trend in contemporary films to fabricate historical biopics of a peculiar sort. Where the usual biopic tends to focus on outstanding men (statesmen, explorers, spiritual leaders, etc.) or everymen in outstanding events (war, crisis, etc.), our contemporaries find it especially amusing to creatively illustrate the lives of history’s great intellectuals. This is still a fairly new thing. While there have occasionally been some biopics about intellectuals (BAIs) throughout the 20th century1, an explosion of BAIs didn’t really start before the 1990s.2 Up to that point, films of this sort have probably been avoided for two reasons, namely because 1) fact-based documentaries (or biographies) about the lives of intellectuals usually get the stories quite right, and 2) because the lives of people who spend hours every day alone reading and writing are, on the face of it, just not exciting enough to merit artistic processing. When movies were, at times, inspired by the lives of intellectuals, then mostly to belittle them.3 True, documentaries about intellectuals are often dull and lack, for reasons of formal constraints to stick to the facts, the psychological insight an artist may have when looking over the life of someone he/she particularly identifies with. Surprisingly though, none of the new BAIs are aiming for deeper understanding when they restage the lives of their departed peers. Indeed, many formally outstanding biographical documentaries with investigative intentions may take a lot more risks, regarding psychological insight, than the lofty anecdotes favored by some of the BAIs that will be discussed below.4 This element seems to connect all BAIs: they are over-positive about the intellectuals they depict, so positive, in fact, that they involuntarily make you wonder what in the world must be wrong with our own intellectuals that could motivate someone to look for more rosy times in the, to a great extent, extremely tortured history of intellectual souls. In short, BAIs are fairy tales, intellectuals our contemporary princes whom we like to imagine to dwell in an enchanted kingdom of inspiration and books.

Consider Tolstoy. In The Last Station, we see the man (Christopher Plummer) sometime at the end of his life (Tolstoy died in 1910) looking like Santa Claus and behaving accordingly. For the younger generation going in and out of his country house, Tolstoy’s words are like gifts which he distributes according to their “good” behavior, and sometimes like verbal lashings, when the writer is thrown off by one of his mood swings. Ho-ho-ho laughs and explosions of anger are not scanty. His wife (Helen Mirren), all the while, provokes the old man’s own “good” behavior with playful seductions, for example when she calls him a cock and herself a chicken, zoological practices which Tolstoy had replaced, at this time of his life, with a lifestyle of austere abstinence and quasi-hermetry. This gives the movie a conflict of the love-story type, which may be tear-jerking, as one critic enthusiastically wrote5, especially for an increasing public of 50+ year olds whose identification with the tensions between the couple may have some positive, cathartic or even absolving effect; the argument being, I assume, that despite of these intersubjective troubles, which Tolstoy, as a writer, and thus as an especially sensitive human being, and his wife, as his loving woman (who, if the time were ripe may have contributed to intellectual activity as well, especially if one pays attention her extremely patient and angelic behavior which make her, really, even more sensitive than her husband), master with such charm that any intersubjective quandaries in the real world should be met with similar grace. Here are two film-stills that nicely portray this kind of domestic bliss:

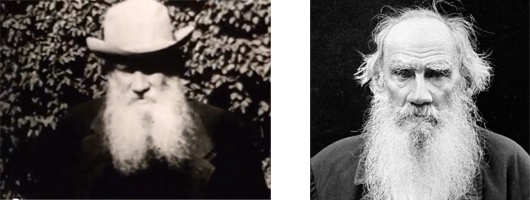

Let’s not kid ourselves. I invite the reader to make his/her own research, but there are literally no photographic depictions of Tolstoy in which he even gives the hint of a smile. Although he lived in a time when photographic images were rather staged, so that he may have payed special attention not to smile when being photographed, a little film strip from 1908 where we see the man in a more spontaneous situation in his garden and in the sun, which is, by the way, very similar to the environment that appears to be the movie’s preferred setting/light, shows the writer more like on the picture below, that is, expressing a deeply worried frown (an expression which can be seen on almost all his photographs like the one next to the 1908 film-still in the garden).

These are superficial observations. But they may suffice to at least doubt those scenes in the film that give the impression of old-age wisdom and intellectual elation. From Tolstoy’s writings of the time one gets the feeling that he was neither particularly happy nor in harmonious agreement about his own spiritual disputes. “Everything is becoming worse and worse, and more and more depressing” (9 July 1908), one can read in his diary. “At present I only want to withdraw and take no part in anything” (21 July 1909), “I am a very worthless man […] it would be good for me to die” (10 January 1909), and spiritual-wise: “the chief mystery […] is my own and other creatures separate identity.”6 Of course, the film doesn’t get by without showing some of this resentment, but the point is not so much to realize that, well, Tolstoy also dies in the film, and that he’s sometimes mean, and that everything is also kind of sad, but to understand that if all the movie has to say about sadness can be reduced to a bunch of exaggerated behavioral attitudes, then it has seriously misinterpreted the essence of its material. If, for example, the film also wants to account for some of the perplexities of a man who wakes up and goes to bed with a visible worried frown on his face and, one is tempted to assume, an even bigger invisible frown in his head, then it utterly fails to do so. But, as I have mentioned above, my suspicion is that movies like The Last Station (2009) have an entirely different aim, which is, to abuse the metaphor, to get rid of the frown and leave things all smiles.

Romanticizing the past in this way may also be a sign of a lack of certain characteristics in the present. The past, or an idealized version of it, thus turns into a kind of substitute or paradise lost, where opportunities and lifestyles are assumed to have been blossoming that are now dead. In The Last Station this lost element is love, temptation, desire, lust, or other forms of libidinal drive that motivate the conflict between the Tolstoy couple. Now when we see Tolstoy experience a “loathsome, criminal desire for [his] wife”, we are, of course, not really longing for self-loathings of our freedom to express more or less all sorts of sexual passions, because we no longer believe that having these passions is something very “criminal” (9 July 1908), at least not in Tolstoy’s sense of the word. And yet, there is something fascinating and, in this film at least, good even about this kind of conflict, be it for the only reason that it visibly spices up the relationship of the old couple. As many great intellectuals have claimed, trying to kill a desire is the best way to keep it alive. The only problem is that, if one would make an effort to really try and understand someone who believes that lust is criminal, contemporary thoughts about the benefits of desire’s short-circuits would quickly vanish. Again, it may be useful to picture a frowning face.

The same problem applies to the general attempt of being overly nostalgic about the lives of intellectuals. While it is surely true that there has never been a time in history which has seen more highly-educated intellectuals, few seem to accept this as particularly fruitful for the breeding of intellectual royalty of the Tolstoy type. Intellectual democracy has, in a way, also kept material for intellectual Fairy Tales at bay. For some of our own intellectuals, this seems to be a severe shortcoming, motivating them to dream about intellectual golden ages like Don Quixote fantasies about the good old days of Amadis de Gaula. Whether BAIs like The Last Station are signs of this feeling or not remains to be seen, but the romantic humanizing of an intellectual like Tolstoy via exaggerated melodramatic gestures should at least strike us as an awkward strategy to portray the systematic efforts of the real writer to appear neither romantic nor, indeed, particularly human.

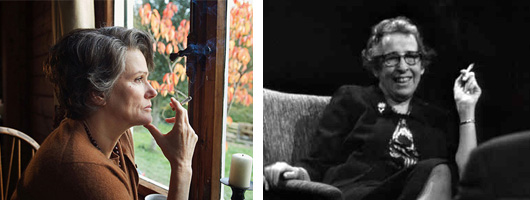

With this in mind consider Hannah Arendt (2013). Sentimentality-wise, this movie makes The Last Station appear almost minimalist. Hannah Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) plays a determined philosopher, or should we say business woman, on an intellectual mission to reveal to the world the truth about itself, which at this time of her real life consisted in dissecting the moral mind of Nazi war criminal Rudolf Eichmann and demystify aspects of pure evil in moral conducts like, for instance, giving orders to exterminate Jews. Arendt thought that, because these things can causally be reduced to other state of affairs, like for instance a psychological inclination to obey orders to give orders to exterminate Jews, they can also be completely understood and explained which was a conclusion many people who wanted to keep the horrors of the holocaust in some ungraspable third realm were unwilling to accept, mistakenly concluding that Arendt’s explanations were really attempts to explain evil away and perhaps even to justify it. Whether Arendt committed meta-ethical mistakes of this sort should not bother us here. More important for our purpose is to realize that Arendt is depicted exactly in the same romanticized way in this movie as Tolstoy in The Last Station, although this movie suggests a somewhat different iconography. Arendt is severely troubled by her thoughts, staring pensively at ceilings and taking meaningful smokes. Here is Arendt in one of the thinking-scenes:

Few real-life depictions of Hannah Arendt’s intellectual behavior give this impression. Indeed, from the many extensive video-recorded interviews (from which the above film-still originates) that she gave throughout the 1960s on various subjects, we get the remarkable portrayal of a woman smiling at all times. In fact, she sometimes gives the feeling that it was physically impossible for her to drop her smile even when thinking/speaking about such heavy-duty subjects as the holocaust. Whether Arendt actually had feelings of thoughts in this delightful, hopeful, or even roguish way is difficult to tell, but at least on a surface level, there is no reason to believe that Arendtian thinking was some kind of deep, mysterious, and tortuous Tolstoyan endeavor as Sukowa’s Arendt, who frowns in practically each one of the many thinking-scenes, seems to suggest. Having an ironic view on the world, on the other hand, may also mean to be able to take a distance which was a quality Arendt mastered to remarkable extents. This attitude may, for example, have allowed her to write such extremely sobering sentences in “Eichmann in Jerusalem” as that “Eichmann […] could […] have cited certain indisputable facts to back up his story if his memory had not been so bad.”7 None of this can be seen in the film which seems to substitute Arendt’s human side with the authority of thought.

But then again, it should be clear by now that we are not dealing here with any historical figure in the first place but with some sort of abstract ideal of intellectual aristocracy. Like for Tolstoy, the over-positive depiction of Arendt may have more to say about our times, in the sense that the deeper urge to grasp the life of a particular woman is only another pretense for celebrating the beauty of heroic cognition. Ironically, however, although Hannah Arendt purports to be a film about an intellectual, and although, presumably, the film deeply admires her as an intellectual (cf. the strings underlying her most important words), if only in a very abstract way, it is not an intellectual film at all (the same could be said of The Last Station). This leads again to the initial supposition that the motivational drive of BAIs lies in the relationship between nostalgia for past intellectual heroes and a present unusually devoid of them.

In contemporary Germany, BAIs are currently living a popularity wave (The Last Station is a German production). In literature biolibs about intellectuals are frequent bestsellers, and the early twentieth century has become a kind of haven for nostalgic minded artists to dream about the biographical routines of their favorite intellectual princes.8 These books, like their cinematographic pendants, are well crafted and sometimes even witty, but most of their anecdotes are chosen for similar melodramatic effect, their intellectual whimsy shallow to the point of dumbing down. On a different level, seeking absolution for intellectual shortcomings by reminiscing past glories may also be a curious form of high-brow nationalism, which is a trend that can also be seen in German historical films that are not about intellectuals (Barbara (2012), Das Leben der Anderen (2006)) which deal with the deconstruction of historical villains in a way that provokes nostalgia for a historical setting where it is still possible to exist as a hero. If those artists creating these fairy tales would have a better memory, one may say, then backing up their stories with indisputable facts seems good advice.

Leave a Comment