Innocent Until Proven Guilty

Johana Ožvold’s The Sound is Innocent (2019)

Vol. 99 (November 2019) by Zoe Aiano

As the variety of approaches to creative documentary continues to expand and the possibilities of the genre continue to broaden, convincing documentaries about other art forms nevertheless fail to materialize, and this is especially true of music. Indeed, there are numerous challenges at play – that of successfully translating a predominantly aural experience into an audio-visual form, that of capturing the emotional and subjective experience of music without ruining it by the necessity of providing information, and the delicate balancing act involved in catering to an audience inevitably composed of both die-hard fans and the passingly curious. Such being the case, it’s no wonder that the formats that continue to dominate are the classic talking heads and music clip combination, or the verité observation of a band at work.

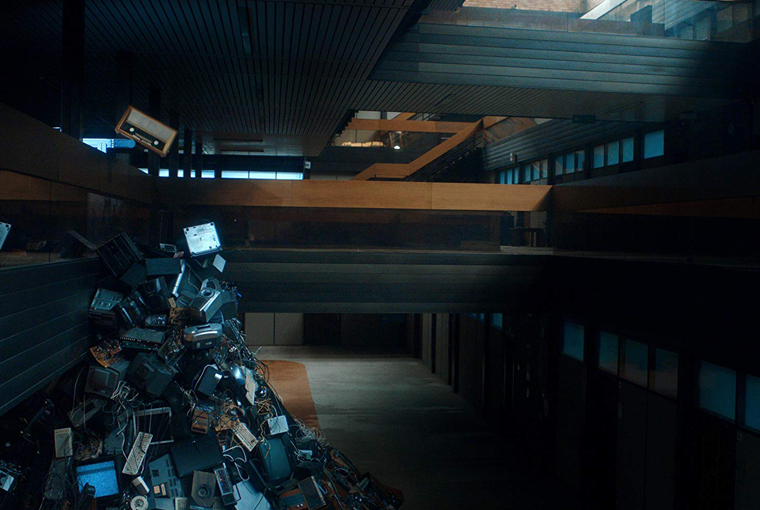

Johana Ožvold’s debut feature The Sound is Innocent does everything possible to shatter these conventions by striving for a new, experiential and stylized method for discussing music, in this case experimental digital music and questions surrounding its production. Ožvold herself acts as a guide through some sort of conceptual warehouse of music filled with old-school technology in various states of destruction – labs, libraries and archives. The talking heads are still there, but they have been transposed onto various types of screens within the space, the camera weaving around them while projections are overlaid on the background or people enter the room to perform different kinds of staged activities.

On a technical level, the accomplishments of the film are quite remarkable. The production levels are extremely high, everything looks perfectly coherent within the confines of the chosen aesthetic and, above all, the combination of pre-recorded materials and live action must have taken an incredible amount of planning and precision. It is, however, entirely unsustainable. Even those who don’t find it grating from the outset are sure to be quickly worn out by the sheer relentlessness of it. In the end, the talking heads are still talking heads – all this visual playfulness does is make the interviews difficult to follow.

This is exacerbated by the fact that, while the actual topics of conversation are genuinely interesting, there is no real consistent line of thought or argument linking the various interviewees. Of course, the entire history of electronic music is far too vast to encapsulate in one film, and the director made the right decision in refusing to attempt to do so. However, the discussion starts fairly incongruously in France with a kind of origin story, although, viewed cynically, it seems more likely that the decision to include this was related to the involvement of French production funding rather than the idea that digital sounds first arose as an exclusively French phenomenon.

As a note on gender in the film, given that both technology and music are two spheres where contributions from women have historically been disregarded or dismissed, it is frustrating to see a work by a woman who is clearly well versed and accomplished in both aspects, yet her physical appearance on screen is in the role of “curious observer seeking knowledge from others”. This is further aggravated by the fact that all of the people offering her answers are men – only one female interviewee appears briefly at the end. (It is also only at the climax of the film that Ožvold is shown in the active role of creator instead of the passive observer.)

Having departed from its historical basis in France, the film does not continue this chronology but rather turns its attention to different practitioners of electronic music, each with their own approach and philosophy. Again, while each of them undoubtedly justifies their place in the film through the interest of their ideas and work, the absence of a tangible link between them makes it difficult to fully appreciate their contributions. In this sense, The Sound is Innocent may well have made an excellent series of shorts, in which each section would make more sense as a standalone segment and in which the demanding rhythm of the film would be confined to a more digestible length. It is unfortunate for all of us that we still live in a world where films need to be considered in terms of their representation instead of on their pure cinematic merit.

Leave a Comment