On the shores of the sea of Azov east of Crimea lies Mariupol, a city of about half a million people, half Russian, half Ukrainian. While Mariupol is currently under the control of the Ukranian government, it is located only twenty kilometers east of the demilitarized town of Shyrokyne which marks the border to the Donetsk People’s Republic, the occupied territories in the Donbass region of the pro-Russian separatists. Mariupol was attacked several times since 2014, and was under control of pro-Russian forces for two months in May and June of the same year, before Ukrainian Armed Forces managed to recapture the city with the help of militia groups from local steelworkers. The city has since been attacked again in September 2014, and on 24 January 2015, when it was hit by rockets coming from the separatist territories. Foreign journalists have described the situation in Mariupol as “civil war-like”, filling newspapers with reports about how civil society is preparing for war.

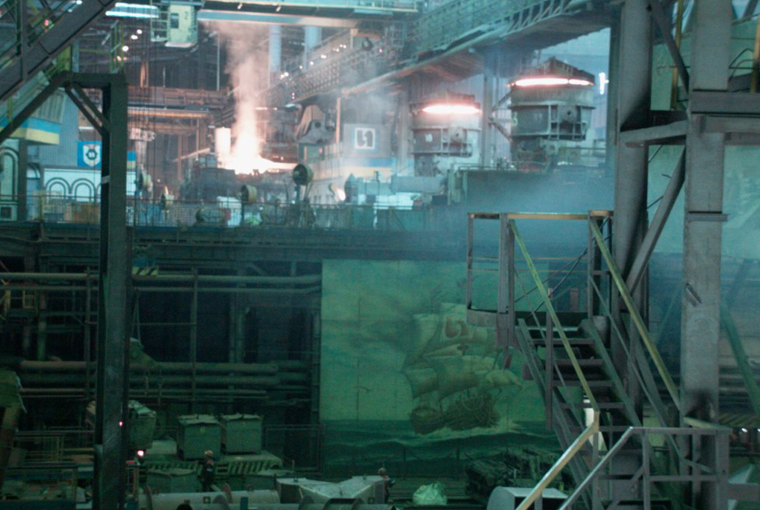

Documentary filmmaker Mantas Kvedaravicius was there too, but his city portrait Mariupolis gives the impression of a society that is hardly aware of the conflict and certainly not ready for combat. A shoemaker peacefully repairs shoes, working like an artist in a studio. A young woman goes fishing with her father. Teenagers prepare for a dance performance to commemorate Victory Day on May 9, which marks the fall of the Nazi regime in 1945. Even the city’s famous steel mills continue to operate. Considering the steelworker’s role in fighting back the pro-Russian forces, this almost seems like a provocation from the director’s side. Where is the war?

Kvedaravicius’ film is an extreme exercise in multiple perspective storytelling, replacing our ideas of so-called grand narratives by focusing on specific local contexts and on the variety of human experiences. Even the film’s title, which is how the relatively large community of Pontic Greeks (roughly 4% of the population) call the city, seems to be a sort of deconstructive effort to question our idea that the War in Donbass can be reduced to simple identity politics of pro-Russian and pro-EU opposition. What do the Greeks of Mariupol identify with? In Kvedaravicius’ film, they seem to be more preoccupied with keeping their own culture alive by playing Márkos Vamvakáris songs on the violin and practicing folk dancing, than with reaching out for arms.

In impressionistic episodes, Mariupolis thus locates identity in the practices of communities no bigger than a family, school class, music group or workshop. This anthropological approach has, of course, nothing at all to do with the politically heated discussions about belonging to one camp or another that seem to dominate in the West. Kvedaravicius’ plea for multiplicity of perspectives rather than for one grand, all-encompassing point of view just shows how far removed from reality these discourses can be. When observing the shoemaker in Kvedaravicius’ film, calls for “unity” as they have been propagated, for instance, by the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, are increasingly difficult to understand.

That innocent civilians need to be protected is a different story, but one that should be independent from whether they are united in identifying with the foreign policy interests of bigger powers. Yet Kvedaravicius doesn’t shun from depicting the face of war, as well as the potential threat to the different communities populating his film. Animals in the city’s zoo nervously run around in their cages, suggesting the vulnerability of the city’s population. In another shot, the ruins of a plaster cast of a Greek statue symbolize the precariousness of this particular minority.

Kvedaravicius’ observations on the social life of small scale groups are so removed from the broader political context that one may wonder whether the director’s own point of view is somehow apolitical, something which the beauty of some of the images doesn’t help to contradict. But his film really puts forth a decidedly political plea: that the portrayal of armed conflict is an integral part of how wars are waged. By refusing to frame the members of civil society as victims in the need of some bigger ideology – unity, freedom or whatever –, Kvedaravicius recognizes the loss of their dignity as their essential threat.

Leave a Comment