When I first heard the title of Signe Baumane’s animated film about depression, Rocks in my Pockets, I rather naively thought it was referring to the way mental illness can weigh you down, both physically and mentally. It turns out that the name refers to Virginia Woolf’s infamous suicide – at age 59, when she drowned herself in the river by weighing her body down with heavy rocks. This is how the seemingly cute title of the film presents its awful subject matter, and sets the tone of the film.

Using a mixture of stop-motion and animation, Signe Baumane carefully spins the tale of her family history of depression. With a few well-placed strokes, Baumane manages to capture the essence of her characters’ feelings, and though their eyes are all drawn in a similar fashion, they are somehow different, and express their pain in various ways. The film is narrated by a voice-over which is at once cheery and questioning. The slight foreign accent of the director’s voice gives the film a universal quality that reminds us that this story could have taken place anywhere in the world.

Skeptics about animation for adults will soon be persuaded when watching the film. The medium is essential to keeping the tone light, and this very lightness is what makes the film so cathartic. The brutal honesty of the narrative makes the viewer see both sides of the story. Therein lies the rub: while depressed people often have a difficult time getting outside that emotion, outsiders see nothing physically wrong, so they sometimes find it incomprehensible. By making depression comic, the director shares a common feeling with outsiders, making fun of her own condition, and therefore humanizing it for non-sufferers.

The film is a Latvian-American co-production taking place in Latvia. It is the story of, as Baumane puts it, “five women in my family and our quest for sanity.” The first, her grandmother Anna, lived in a lonesome cabin in the woods and had to raise eight children on her own. Then there are her cousins: Miranda, an artist who killed herself after giving birth to her first child; Linda, a medical student who hallucinated so badly that she ended up in a mental institution for a long time; Erba, a music teacher, who also heard voices and hanged herself in her living room. Finally there is the protagonist herself, whose post-natal depression along with the voices she heard, and a period of incarceration, inspired her to make this movie.

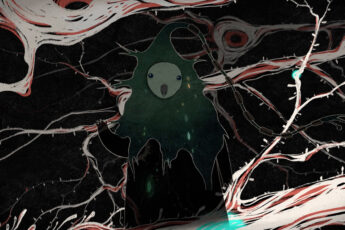

It is with such heavy family history that Baumane explores her own sanity and, literally, illustrates her own ghosts. The personified figure that represents depression is a devil-like creature, white with red eyes, who lurks in corners while she is sleeping and awake. Luckily there is also a good one, a green creature that looks like a friendly monster on television. The illustrations are very powerful, people transform, change, get bigger and smaller. When perfect Linda has a mental breakdown on her front lawn, she turns into a terrifying bird with sharp talons and eyes of fire. When Miranda falls out of love with her husband she becomes a giant, slippery fish in his arms. As for the psychiatrist, she is a dull-eyed, uninterested woman, who looks down at her paper and speaks in a scratchy voice. While the voice-over suggests that the woman tries all the pills herself before dishing them out to the patients, her head becomes a frog with a long pink tongue which darts down onto the desk and slurps up a long line of pills.

The film is not overtly political, and although all these stories took place in Soviet Latvia there is no implication that it was any worse or better than before or afterwards. The medical treatment of doctors is openly deplored, through powerful images. The isolation and silence of Linda’s situation for example is illustrated by her disappearing into a pill bottle to disappear in a fog of white pills.

Virginia Woolf said, “If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.” The courageous debut by Signe Baumane, which uses the example of her family primarily to question her own sanity, illustrates this quote. A universal story about a universal problem, this film should reach a wide audience and contribute to making more sense of this bewildering, disorientating condition.

Leave a Comment