Who Watches the Watchmen?

Gábor Zsigmond Papp’s Life of an Agent (Az ügynök élete, 2006)

Vol. 32 (August 2013) by Colette de Castro

Papp has produced something curious. His film Life of an Agent is actually a compilation chosen from police training videos which were made during the era of János Kádár, general secretary of the People’s Republic of Hungary from 1956 to 1988. We are introduced to the story by slow panning of the camera through the abandoned government film studio in Budapest. The first scene is introduced with the words “There used to be a secret film studio belonging to the interior office”. It seems that these government-funded films were mostly made for ordinary police officers, but a few were kept secret, so much in fact that even the projectionist had to exit the room while they were screening. These were the training videos for agents of the special police force during the Cold War, discovered in that same film studio at the dawn of the 21st century.

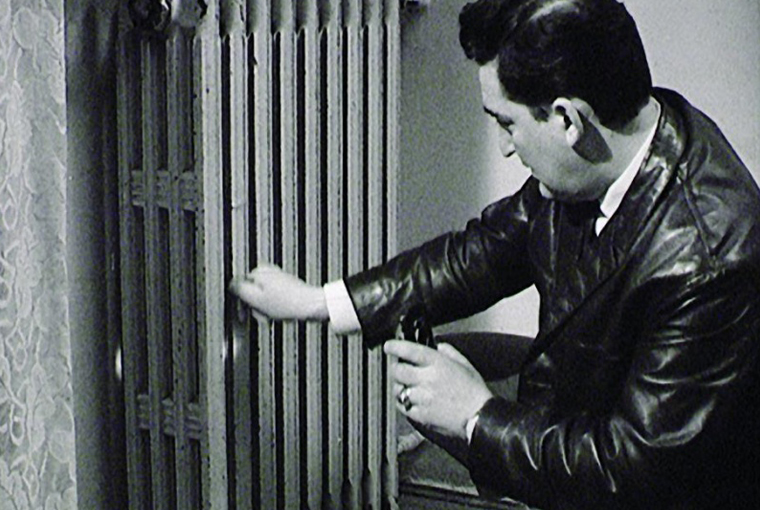

Life of an Agent is broken into four main parts of about equal length. Part one, “Where to put the bug?,” focuses on how to subtly pursue a suspect. It describes how to film someone with a secret camera hidden inside a bag; the filmmakers are clearly proud of the existence of this ready-made compartment, as the camera lingers on the invention. Part two is baptized “Introduction to home raid” and describes how to copy a suspect’s keys when he is undressed during a false medical test. When it comes to the actual raid, there is much ado about such details as replacing a single hair that has been taped across two surfaces, or shifting through the flour jar with a wooden spoon. In the case of authorized raid, other insidious instructions are given, and they warn that the behavior of the suspect should be carefully and constantly observed.

Part three – “Introduction to enlistment” – explores the main techniques for recruiting new agents. State security was aimed at knowing every aspect of a citizen’s life. In one grueling scene, they demonstrate how a government official can not-so-subtly threaten to harm a potential recruit’s children and wife if he does not comply. The fourth part is entitled “Effective network” and focuses on the people who control the agents, those who “Watch the watchmen” if you will. These high-powered citizens are called ‘keepers’. It also gives details on how to run a “conspiracy flat” – a place where they can hold secret meetings without the possibility of running into someone they know.

Watching the film is unsettling. The commentators say that there were 70,000 people being directly surveyed during the Kadar regime, as well as 30,000 more indirectly, spied upon by about 20,000 agents. This is training material that promotes intrusion into citizen’s intimate space. The film got me thinking about how and how internet surveillance today is not dissimilar to what was happening in these kind of surveillance situations. It may seem dramatic to compare a totalitarian Socialist regime to government control over the internet, but there is truth in this. In both cases, there is the element of the unknown: we don’t know how much we are being watched and this dubious reality is almost as disconcerting as the surveillance itself. Of course, we hear horror stories about people who are being watched and then wrongly accused, but surely this can’t affect us directly?

While we are already made aware that internet surveillance happens to everyone, it is impossible to know to what extent. Here of course we use the internet as a general term: media surveillance often also extends to cell phones and other technology channels. Gary Kovacs, CEO of a large internet virus protection company, recently stated in a talk about trackers that: “With every click of the mouse and every touch of the screen, we are like Hansel and Gretel leaving breadcrumbs of personal information everywhere we travel through the digital woods.” This phenomenon is known as ‘behavioral tracking’, mostly it is used for advertisers and we can assume that it is mostly harmless. But one of the most interesting components of the internet community is how wide-spread it is. In the case of the Soviet countries it is possible in retrospect to pinpoint the ‘hunting’ to one government, but the internet is global, and thus much more anonymous. In the future, traces such as those found in the film will be able to be erased almost instantly, and so questions of which government, which company, or which individual committed which crimes will get more and more difficult to answer.

Compare the details in the film to the way people can be patrolled today on the internet – millions of people at the click of a button. This is why the degree of attention to detail described seems all the more astonishing. Rather than needing to make copies of keys, hide secret cameras or delve into the flour to find information about a person, all that is required today is a password or a series of numbers.

The overall atmosphere of the film is not dissimilar to that of an American police-thriller. Close-ups, mysterious music and, agents hanging around in dark aquariums with close-ups of eels wriggling in and out of holes. We can imagine that making these videos must have been some of the best fun within a dreary routine, perhaps even part of the pitch for new policemen.

Life of an Agent is on the whole unapproachable for an English speaking public. Take the DVD, for example: all the extras are in Hungarian, and you have to navigate the menus before finding the English subtitle switch. The film is also interspersed with “Illusztracio”, extra scenes which have been added to make the film more exciting. It’s difficult to tell at first whether or not the commentary is part of the original videos or not, we only know that is because the ‘narrators’ are mentioned in the credits. The director’s choice to carry modify the document in this way could certainly be considered bizarre, but luckily, Papp has managed keep with the style of the originals most of the time.

Part of this confusion dissolves when you learn that Life of an Agent is playing at the Memento Park in Budapest as part of an exhibition called “Stalin’s Boots”. The film seeks entertainment value, thus integrating ‘action scenes,’ scoring, a commentary. The director’s choice to modify the document in this way could certainly be considered bizarre, especially because it means the combination of a set of very historical documents with another set of very invented ones, we don’t really know what kind of thing we are dealing with. Nonetheless retaining a core of useful historical information, it is muddied for amusement-parks and a larger audience.

Frustrating though this slight muddling of information may seem, with the right persuasion a researcher could probably find a way to access the original videos. The team that made Life of an Agent found no credits for actors, filmmakers or directors of these training videos, so while historically valid, their very existence is ghost-like and fleeting which accounts for the extras.

Leave a Comment