Seeing the Truth Through Smoked Glass

Štefan Uher’s The Sun in a Net (Slnko v sieti, 1963)

Vol. 46 (October 2014) by Nicholas Hudáč

Although often thought of as an appendage to the larger, more known Czech New Wave, Slovak films of the 1960s were at the forefront of the Czechoslovak film resurgence. Among the films made prior to the aborted Prague Spring of 1968, one particular Slovak film stands as a gatepost within the history of the Czechoslovak New Wave. With its intimate storytelling (and contemporary literary source material), unique sound design and score, impressionistic camerawork, and emphasis on personal and internal conflict (instead of staid Socialist Realist drama) Štefán Uher’s 1962 feature film, The Sun in a Net (Slnko v sieti) is often credited with launching both the Czech and Slovak New Waves. Its bold stylistic and formal innovations would be reflected in many of the more widely known (and certainly much more financially successful in the West) films of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

Uher’s movie follows the troubled lives of a teenage couple in Bratislava, an amateur photographer named Fajolo Fajták (Marián Bielik) and his young love Bela Blažejová (played by Jana Beláková), whose troubled relationship hits a snag with Fajolo’s forced enrollment in a summer labor program in a sleepy country town far away. Bela and Fajolo’s separation, their subsequent summer loves, and tentative reconciliation drive the film’s meditations on truth, memory, and identity in a way wholly familiar to us as contemporary viewers. Surrounding this teenage drama are the troubles of Bela’s sun-blinded mother and unfaithful father, as well as a coming solar eclipse.

While the concept of adaptation is often discussed in the realm of medium-specific theory, I’d like to take the opportunity to focus on a rather unexplored side — adaptation as an act of political and ethnic identity. Based as it is on three short stories of Slovak author and screenwriter, Alfonz Bednár, The Sun in a Net, is (in the purest sense of the word) a cinematic adaptation of a literary work. However, on a secondary level, the film is also an adaptation of identity, a movie concerned with translating an earlier mode of ethnic identity (Slovak) into a new idiom for a new time— a Czechoslovak identity.

A New Visuality

Although a rich tradition of urban-themed movies exists from the very beginning of cinema in the Czech Lands, prior to The Sun in a Net, Slovak cinema and cinematic depictions of Slovakia were often limited to folkloric rural dramas or cinematic celebrations of natural beauties absent in other parts of the larger country, be it Austro-Hungary or the first Czechoslovak Republic. While Czech films explored the urban life of Prague from the silent film era onward, Slovakia’s sole contribution (as an indigenous cinematic production by Slovaks) to First Republic cinema was a cinematic adaptation of the life of legendary Slovak bandit, Juraj Jánošík in 1922. Even after the formation of Fascist Slovakia’s national film company Nástup in 1939 (the first organ of domestic film production in the Slovak lands), Slovak films were primarily limited to Fascist propaganda or documentary films on rural traditions and customs. This visual compartmentalization of Slovakia was further aided by Czech productions both before and after World War II, which sought to preserve this distinction between the Czech lands and Slovakia at the expense of allowing the development of a contemporary cinematic language for Slovaks in line with Slovakia’s modernization and growth. In order for an exotic area to remain exotic, care must be taken not to contaminate it with intrusions of the contemporary.

Perhaps the best way to rebel against such exoticism, is therefore, to adulterate and subvert the ideal image. In this sense, The Sun in a Net is very much a subversion of the traditional visual depiction of Slovakia. For Uher, Slovakia of the 1960s exists as a land of contrasts — of apartment building courtyards and quiet forests, of fishing ponds and streetcars. In a particularly striking part of the opening title sequence, the camera focuses on a bird’s nest, complete with eggs, floating idly in a river. As the sounds of birds and water fill the air, waves wash against the rocky shore; the camera pans with the motion of the water, carrying the camera across the rocks, where it lingers on a misty reservoir – a shot that would have been aesthetically in line with early celebrations of Slovak natural beauty. The allure of such serenity, which highlights Slovakia’s often quasi-mystical connection with nature and rugged mountains, is immediately disrupted with a jump cut to a crowded Bratislava street, filled with the rumbling of trams and traffic, geometrically disrupted and fragmented by shop windows, pedestrians, and a forest of wires and antennas. Instead of retreating into the staid familiarity of Slovak forests and mountains, Uher brings us into contemporary Bratislava, a city which would be indistinguishable from any other Czechoslovak metropolitan area outside of the vernacular language of its inhabitants. This juxtaposition continues throughout the film, frequently returning to such idyllic stereotypes of Slovak pastures in the harvest and peaceful swimming ponds, after visual excursions through the scarred and pitted landscape of urban Bratislava.

Interestingly enough, these two scenes embody the inverse of the opening of Czech director Karel Plicka’s pre-war cinematic paean to Slovakia, The Earth Sings (Zem spieva), where the geometric clutter of Czechoslovak urban industrial areas gives way to the majestic natural beauty of Slovakia as seen from a traveling train. Plicka saw Slovakia as an idyllic refuge in the midst of a rapidly industrializing country, a place where traditional methods of agriculture and pastimes still existed long after the Czech lands had modernized. However, by 1962, this facile comparison had begun to ring false for Czechs and Slovaks alike. Uher plays on this notion by finding aesthetic beauty in the scarred concrete and antenna forests blanketing post-War Bratislava. Aided by the deft camerawork of Stanislav Szomolányi, Uher transforms ordinary views of the city into geometrical compositions that strongly echo not only the work of pioneering photographer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, but Cubism and Constructivism as well.

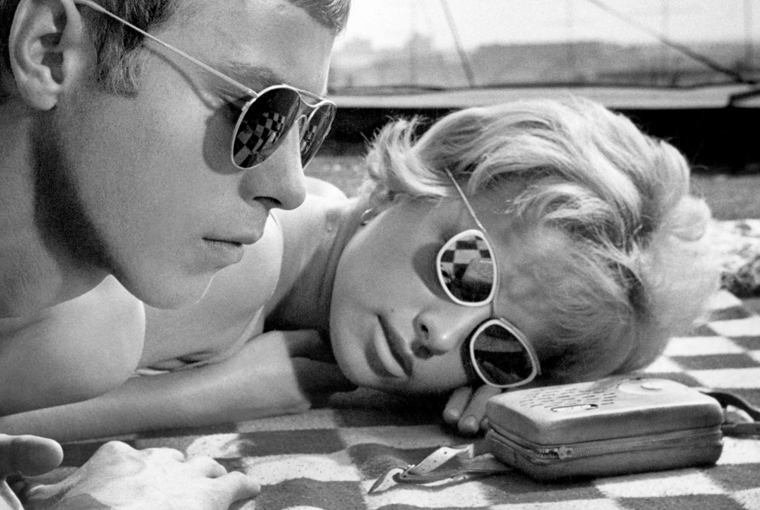

These abstractions and deconstructions of images and space are common recurrences throughout The Sun in a Net, though Uher is careful not to make them overwhelming. Characters are viewed through lenses (often distorted) and mirrors, much as the eclipse of the titular sun is viewed through panes of smoked glass or indirectly. The more standard cinematography of other scenes calls to mind the works of more traditionally minded Czech and Slovak productions set in Slovakia. Shirtless youths pitch hay by hand in the fields of the rural town Meleňany, transported by horse-drawn wagons. In the evenings, young lovers stroll through the quiet fields, coupling in the grass. Simultaneously, Bratislava itself provides equal opportunity for such actions in the film. Bela and Fajolo rendezvous on apartment building rooftops, safely hidden from prying eyes by the forest of antennas and the commotion of the city. Underscoring the new imaging of space is Bela’s blind mother, who tearfully asks various characters to describe the world around her (which they often do untruthfully), a world she can no longer see or understand. Just as Bela’s mother finds few recognizable references in the world surrounding her, the Slovakia present in Uher’s film bears only scant resemblance to the Slovakia the previous generation knew.

Uher’s imaging of urban Slovakia as a land of unnoticed beauty mirrors Fajolo’s own fascination with the visual culture of 1960s Slovakia. Fajolo’s room is covered with photographs, advertisements, disembodied images and accidental montages. In one particular scene set in his homemade darkroom, Fajolo contemplates the truthfulness of hands, comparing the hands of laborers first to his own, and eventually to an advertisement for Gly Doreé hand cream. Although Fajolo laments that his hands are closer to the delicate, untouched hands in the advertisement than to those of the workers he constantly photographs, he takes a palpable pleasure in viewing the collection of the photographed hands in various different contexts which cover his room. Fajolo is captivated by the aesthetic differences in the hands, marveling at the textures and how they are the most “fascinating” part of the human body. At the same time, Fajolo avoids resorting to old-fashioned Socialist realism in his assessment of his collection. These hands, he reasons, are valuable for their innate truthfulness, not their ability to labor or bring glory to the workers of the world. The hands tell the truth, even though their images can be manipulated, and for Fajolo as well as Uher, the truth telling ability of visual images in the face of such artifice is vital.

Social Consciousness, Adaptation, and Literary Leanings

Uher, like many of the Slovak filmmakers of the post-World War II generation, initially received his early training as a documentarian1. In a conversation with noted Czech film historian and critic Antonín Liehm, Uher acknowledged that his early schooling was influential on his trajectory as a director, saying, “I was a ten-time documentary filmmaker, and from documentary filmmaking I gained a respect for social consciousness.”2 Uher’s feature film debut in 1961 was a traditional teenage drama about the tribulations of joining a new school. We from Group 9A (My z deviatej A), was a Socialist drama about proper socialist education, however the material fell flat and was not particularly successful despite its potential. As Slovak film historian Václav Macek put it: “We from Group 9A could have been a psychological film about the joys and sorrows of coming of age, but it was not.”3 Uher’s fascination with the concerns of the youth was undeterred, however, and his keen eye for social problems saw a renewed focus in his next film, The Sun in a Net. Where We From Group 9A was hampered by old-fashioned didacticism, The Sun in a Net gave voice to the problems and complaints of ordinary Slovak teenagers coming of age in 1960s Bratislava.

The film itself is an adaptation of three short stories by Alfonz Bednár – Fajolo’s Contribution (Fajolov príspevok), Pontoon Day (Pontónový deň), and The Golden Gate (Zlatá brána) – published in Slovak periodicals, immortalizing the questions and concerns of the Slovak youth of the late 1950s and 1960s. The film’s episodic structure4 belies its serialized source material — the film embraces the defamiliarizing switches from scenes and plot lines as if it were a collection of anecdotes instead of a single film. Bednár had begun to work with the Studio of Feature Films in Slovakia in 19605 (around the same time as Uher himself), accepting a position as a dramaturge and scriptwriter within a group under the supervision of Albert Marenčin, an accomplished author and scriptwriter. On April 9th, 1962 the cultural authorities green-lighted a film adaptation of Bednár’s stories, while simultaneously recommending that The Sun in a Net be published in book form. Originally the slightly more established Stanislav Barabáš was chosen to transform Bednár’s work into a working film, however, Barabáš declined and Marenčin appointed Uher in his place.6

In a film marketplace saturated with Stakhanovite workers and heroic Communist soldiers fighting against grim-faced genocidal villains, The Sun in a Net was a breath of fresh air. Uher himself was quick to give the credit to his screenwriter, the very same Alfonz Bednár who wrote the original source material, and who collaborated closely with the director in adapting his stories into a workable script:

My big break was [Alfonz] Bednár’s screenplay. At the same time, Bednár really didn’t follow film, it was a marginal concern for him, but nonetheless he opened up a lot of possibilities with his prose.7

Since Bednár’s original draft of the script far exceeded the possibilities of a single, black and white feature film, Uher’s main task lie in shortening the working script. However Bednár’s influence remained; indeed, the adaption of Bednár’s mix of “deforming”8 street slang and more literary poetic musings helped inform the film’s unique aesthetic. Bednár was himself a man uneasily adapting to a new role in the new era. He achieved his first successes during World War II as a philologist, translator of American fiction, and author of young adult literature. From 1945 until 1959, he served as an editor at the Pravda publishing house and enjoyed moderate success with his novel The Glass Mountain (Sklený vrch) about the Slovak National Uprising. Even with his success, however, Bednár often found himself listed as one of the authors whose work was forbidden from publication9 or, if published, heavily censored. Soon after the thawing of Soviet cultural policy, Bednar was allowed greater autonomy, and consequently wrote and published some of the first Slovak fiction to take hesitant steps towards breaking from Soviet ideological constraints while flirting with new kinds of realism. Furthermore, Bednár’s own growing reputation as a writer with keen insight into the emotional heart of the new Slovak society lead many to consider him one of the best chroniclers of early 60s Slovak youth culture10. Even in the realm of screenwriting, Bednár’s success was known. As the Slovak film historian Jelena Pašteková writes:

[Bednár] became the first Slovak professional whose scripts were regarded for their own distinctive artistic value, and whose scripts eventually lived on even in book form.11

Indeed, Bednár’s scripts were so popular, that in 1968 they were collected and published outside of academic circles, an honor afforded to few of the few scriptwriters of his generation12.

One of the central components to Bednár’s enduring popularity was his ear for idiom. The dialog in The Sun in a Net sparkles with the lexicon of the youth, skirting the edges of what was then permissible in literature and cinema and even eyeing Hemingwayesque brevity13 at times, all the while inventing new and suggestive slang. (In one memorable scene, Fajolo and his romantic rival display a new usage for the word for “ski lift” and its uplifting effects to describe an attractive woman.) A cinematic record of unofficial, explicitly Slovak slang would seem at first to be a profoundly nationalistic move; however, the contrast between the city slang of Fajolo and Bela and the more standardized Slovak of the parents and older supervisors highlights the search for a new mode of communication. Furthermore, the celebration of dialectical differences (such as the hard, clipped Bratislava accent of Mr. Meg, the smoking man in the courtyard) serves as an active reminder of the linguistic differences found even in 1960s Slovakia, while simultaneously injecting a sense of realism into the film. Finally, the shift in language functions as a demarcation, a transition away from the jargon of Soviet phrases and towards a celebration of spoken, informal language.

Following the film’s premiere in 1963 at the Festival of Czechoslovak Film in Ustí nad labem and its subsequent release, it was hailed as being “a successful artistic experiment, which used new means to capture the face of today’s youth on film”14, putting the problems and emotions of modern Socialist youth forward, in a less adulterated light. The film was a smash success during the 1963 award season, winning the Czechoslovak Critics’ Choice award for best film from 1962. It went on to win another honorary mention in 1963, and furthermore became one of the most acknowledged international successes of early 1960s Czechoslovak cinema, with respectable showings in various international film festivals. This international success paved the way for other Czechoslovak directors. Without the international success of The Sun in a Net, it is hard to imagine a scenario where other internationally-minded Czech and Slovak directors such as Jiří Menzel, Elmar Klos, and Ján Kadár would be not only able to gain permission to exhibit their films abroad but encouraged to seek international distribution for their films in the mid-60s.

New Villains, No Need for Heroes

Perhaps the most crucial narrative innovation that Uher brought into the realm of Czechoslovak cinema was a fundamental shift in the focus of filmmaking and possibilities of the cinematic narrative. Before Slovakia’s secession in 1939, Czech films on Slovakia rarely strayed from retellings of folklore or panoramas; indigenous Slovak feature film production didn’t exist in the modern sense until Slovakia’s departure from the first Czechoslovak Republic15. Such an unexpectedly late start meant that Slovak feature filmmaking was, from its inception, steeped in the toxic mix of extreme nationalism and xenophobia. As is logical for an industry widely supported, trained, and financed by Nazi Germany and its Slovak puppet state, early Slovak cinema was more interested in prolonging and increasing ethnic and political divides than exploring the possibilities of the new medium. From its infancy, Slovak popular films from the Fascist period were directly involved in perpetuating this isolationist schism. The Slovak film scholar Petra Hanáková points out that much of the earliest domestic products of the newly created film industry16 in the Slovak lands were often pointedly anti-Czech, as benefits a Fascist government attempting to justify secession and consolidate power. These propaganda films featured a prominent focus on “Anti-Czech” themes, though as Hanáková points out, other external “enemies” are featured — Jewish residents of the Slovak lands being the most prominent. The most dangerous, to Slovak propagandists and Fascist filmmakers, was a trifold combination of “Jewish-Czech-Bolshevik”, often fused into one noxious caricature17. Such characters made for easy propaganda, however, the end of the conflict saw the demise of these perverse creations.

Following the war, the inverse of such Fascist caricatures could be easily manufactured when needed by the now-dominant Socialists. Although the Jewish-Czech-Bolshevik was the driving engine of conflict in wartime propaganda, Socialist cultural policy dictated that the antagonists of the 1950s were often one-dimensional Fascists or class enemies. As the scars of the war healed and the influence of Stalinism slowly faded, other sources for conflicts needed to be found. For nearly 10 years, Slovak cinema focused mainly on the tragic martyrdom of Socialist partisans in the Slovak National Uprising, or war dramas.18 In this light, The Sun in the Net was a revolutionary step forward. Not only was the film bereft of the “terrifying” presence of Czech, Jewish, Bolshevik, or Fascist antagonists, but it instead focused its gaze inward, finding its conflict within the normal confines of modern-day Slovakia — namely the troubles between boyfriends and girlfriends, and ordinary husbands with everyday infidelities.19 Furthermore, The Sun in a Net dispenses with the need for traditional heroes — both Bela and Fajolo are depicted as imperfect and uncertain, as teenagers tend to be, without the need to “fix” themselves in accordance to the new Czechoslovak experience. They are already perfectly adapted to it — the dramatic elements come from their own inability to successfully translate the concepts and mores of the older generation to the new world.

Modern Sounds for a Modern Movie

Even the soundtrack saw an infusion of new blood and ideas into Czechoslovak cinema. Instead of choosing music veterans such as Jan Siedel or Zdeněk Liška20, Uher elected to go with a young composer, Ilja Zeljenka, who had an interest in the avant-garde and contemporary pop idioms to score The Sun in a Net, heralding the choice of another relative unknown. Though Zeljenka was to go on to become one of the most prolific post-War Slovak composers, in the early 1960s he was a relatively minor figure, a student of the then politically-undesirable Ján Cikker and dramaturge at the Slovak Philharmonic. Zeljenka’s own adaptation to the changing political climate mirrored Bednár’s. Although his early work was relegated to the strict compositional guidelines imposed by Socialist cultural authorities, the loosening of artistic control in the early 1960s allowed Zeljenka to expand and broaden his musical repertoire. For The Sun in a Net Zeljenka experimented with pop idioms (reverb-laden guitar instrumentals reminiscent of 60s European and American dance hits), sound collage, and electronic effects, creating an aural collage reminiscent of the film’s own modernist visuality. Pop music competes in various scenes with the sounds of machinery, and transistor radios (a sign of growing affluence and connection with the wider world) blare music in time with the rumble of trams and buses.

Even Uher’s usage of dubbing dialog for his non-professional actors was to have a profound effect on later films of the Czech and Slovak New Wave. Both Marián Bielik’s Fajolo, and Pavol Chrobák’s Supervisor Mechanic Blažej were voiced by other, more experienced, professional actors — similar to a technique employed by Jakubisko in his critically acclaimed Birds, Orphans, and Fools (Vtačkovia, siroti, a blazni) where one of his lead actors, the Frenchman Philippe Avon, needed to be voiced by veteran Slovak actor Juraj Kukura in order to overcome the language barrier. Such voice-overs are, in themselves, an adaptation, an attempt to overcome limitations vis-à-vis a medium-specific solution only available in film.

Cultural Impact and Ownership

Critically, The Sun in a Net was wildly popular with directors and film students within Czechoslovakia as well as the general public. With regards to its impact upon directors, the film’s formal and stylistic innovations were to become highly influential on both sides of Czechoslovakia and even beyond the confines of the New Wave. Szomolányi’s combination of lyrical and abstract camerawork rippled throughout the Czechoslovak film industry; its effects can be felt in a wide range of films such as Zbyeněk Brynych’s decidedly non-New Wave war drama The Fifth Horseman is Fear (…a pátý jezdec je Strach), which often reduced Prague to a similarly geometric tangle as Uher’s Bratislava. The poetic freedom of image which fills Uher’s film, along with its episodic structure, paved the way for other such abstract mediations on social concerns like Jan Neměc’s A Report on the Party and the Guests (O slavnosti a hostech) and Elo Havetta’s The Celebration in the Botanical Garden (Slávnosť v botanickej záhrade). At the same time, Uher’s emphasis on personal and emotional conflict and youth engagement directly presages such celebrated New Wave films like Miloš Forman’s Czech work (e.g. Black Peter). Finally, Uher and Bednár’s adaptation of the latter’s literary works also opened the door for more Czech and Slovak films based on contemporary literary sources, ranging from works by Ladislav Grossman to Bohumil Hrabal — and furthermore created a valuable precedent of directors collaborating closely with authors on the adaptations of their source material21.

The question remains as to whether or not one can consider The Sun in a Net a Slovak movie, as opposed to Czechoslovak film? While in Czech, Slovak, and English language historiography, The Sun in a Net remains celebrated as one of the greatest Slovak films of the 1960s, I would like to propose an alternate historiography: The Sun in a Net is instead the first intentionally Czechoslovak film made with such an aim in mind, and as such belongs to both categories. My reasoning for such is two-fold; on the one hand, The Sun in a Net explicitly plays with notions of Slovak identity in ways that resonate with Slovaks looking to carve out a new identity as equal partners in a reunited (but scarred) Czechoslovakia. Secondly, the film’s broad generational appeal to the younger Czechs and Slovaks of the reunited republic saw a shared appeal in ways that much of the 1950s cinema (with its rigid Socialist Realism and focus on external conflict) could not match. By providing an alternative to the rigid taxonomy of Czech or Slovak identity, as well as experimenting with new thematic and formalist techniques, The Sun in a Net not only ushered in the Golden Age of Czech and Slovak cinema, but also perfectly embodied the brief flowering of Czechoslovakism taking root in that country during the early 1960s.

Are the sources to this article still available somehow?