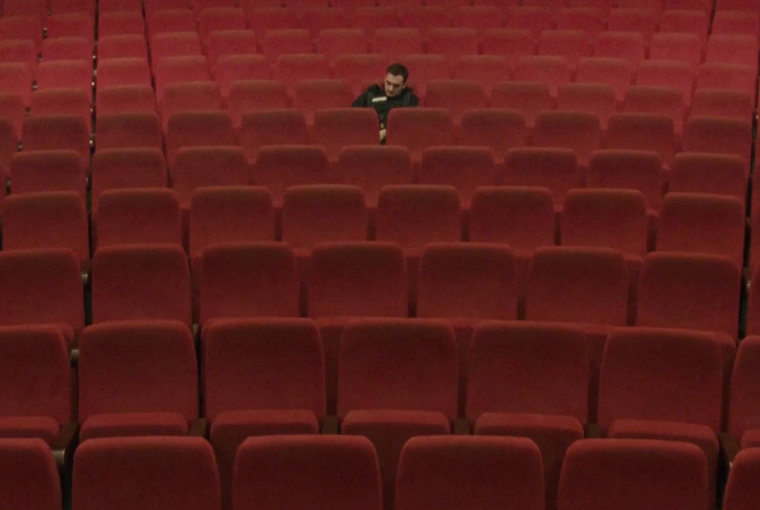

The state of being physically or mentally cooped up appears to be a cinematographic constant that the receding COVID-crisis had little to no effect upon. In popular movies, confinement comes in many forms. There are prison films, films about prison escapes, films about abductions, films about hijacking, films about trapped housewives and domesticated husbands, films about lands of promise and skies of despair. Regardless of the medium, genre, time, or place, humans seem to be constantly stuck, trying to break out from somewhere and finding themselves on the move to somewhere else.

With its penchant for realism, the trope of immobility in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern European cinema is most often wrapped in failed stories of migration. Of the films this journal has discussed over the years, Francesca (dir. Bobby Păunescu, 2009), Bibliothèque Pascal (dir. Szabolcs Hajdu, 2010) and Morgen (dir. Marian Crișan, 2010) all depict narratives of aborted, delayed or interrupted journeys that culminate in situations of entrapment. While the characters in these films still dream and drive westwards, in more recent years, the direction of the journey has reversed. In films like He Was a Giant with Brown Eyes (dir. Eileen Hofer, 2012) and Take Me Somewhere Nice (dir. Ena Sendijarević, 2019), characters who have lived in the West travel back eastwards in search of their origins. Life abroad, it seems, does not satisfy the human need of feeling at home.

There are certainly many reasons that could explain this shift. With the maturing of the Erasmus generation, filmmakers who live and work abroad seek creative material at home (and may confront barriers when making films about their adoptive society). The aftermaths of the financial crisis may also have turned narratives about disillusionment into commonplace. Films that depict liberalism as, in the words of Ivan Krastev, “the God that failed”, have been around since the early 1990s, of which current visions of Western collapsology are extreme variations. On the other hand, the cultural homogeneity brought about by European integration has at least complicated more traditional go-West narratives. The problems of capitalism may not care much for national borders. Even nationalism, as Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán noted in 2016, “once condemned, despised, looked down upon and treated with contempt”, is now the EU’s “jointly held position”. Little is being done to prove him wrong.

It will be interesting to observe what the COVID-19 crisis will add to the (im)mobility narrative. Looking at this year’s film festivals, the dominant narratives appear to have already shifted towards inner-social conflicts, a trend that reflects the European countries’ increasing focus on domestic affairs. For cinema, however, this shift may not be unwelcome. Radu Jude’s recent take on the hypocrisy of societal norms of Bucharest’s educated classes is solidly anchored in the cultural microcosm of the film’s setting, but can easily be enjoyed by audiences in Barcelona, Berlin or Budapest. Instead of gazing at interrupted journeys and failed odysseys, stay put! Subsidiarity applied to cinematographic storytelling may allow you to travel after all.

***

In this month’s issue, we wrap up our coverage of the DOK.Fest Munich with a review of Monica Lăzurean-Gorgan, Michaela Kirst and Ebba Sinzinger’s Wood – Game-Changers Undercover, a documentary about illegal logging. Colette de Castro again visited the Molodist film festival in Kyiv, where she was part of the FIPRESCI jury last year. In Ukraine, she saw Milica Tomovic’s Celts, a personal take on the Yugoslav Wars, and Eugen Jebeleanu’s Poppy Field about a gay policeman in Romania. You will find an interview with the director of Poppy Field in our Interviews section. Finally, Jack Page discusses Andrey Konchalovsky’s unstinting vision of the Novocherkassk massacre in Dear Comrades!.

We hope you enjoy our reads.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment