Women in Prison

Binka Zhelyazkova Retrospective at Thessaloniki 2021

Vol. 120 (December 2021) by Savina Petkova

The Thessaloniki International Film Festival’s 62nd edition hosted the first retrospective of Binka Zhelyazkova’s work outside of her native Bulgaria. Over the course of the festival, those who wished to see the films in person were treated to two screenings per day in a cozier counterpart to the much bigger Olympion venue on the ground floor. Routinely ascending the same steps to the Pavlos Zannas room served as a sort of preamble to the journey back in time one agrees to take when watching these films, a peregrination that would soon become habitual. Descending them once the film was over also provided precious time for the viewing experience to sink in before the outside world demands attention once again. Zhelyazkova’s films do not ease you in, neither do they let go easily, without leaving any marks. Not withholding the sense of idealism which permeated the filmmaker’s works, programmer in charge Dimitris Kerkinos describes her as “uncompromising to the end, faithful to a humanitarian cinema which criticized the regime and charted the intellectual crisis of socialism.” Binka’s name is only mentioned in passing in an otherwise extensive piece by Ronald Holloway1 as pertaining to the “revival” of Bulgarian cinema in the 60s. In order to tell the story of the rising “New Wave” at the time, Holloway pairs her with another filmmaker of the 20th century in Bulgaria, Rangel Valchanov. However, in light of this retrospective, his decision to pair them does little else for an overlooked canon than to reiterate how things were back in the days: Valchanov’s films were deemed appropriate and lauded; Zhelyazkova’s films were challenged and often shelved.

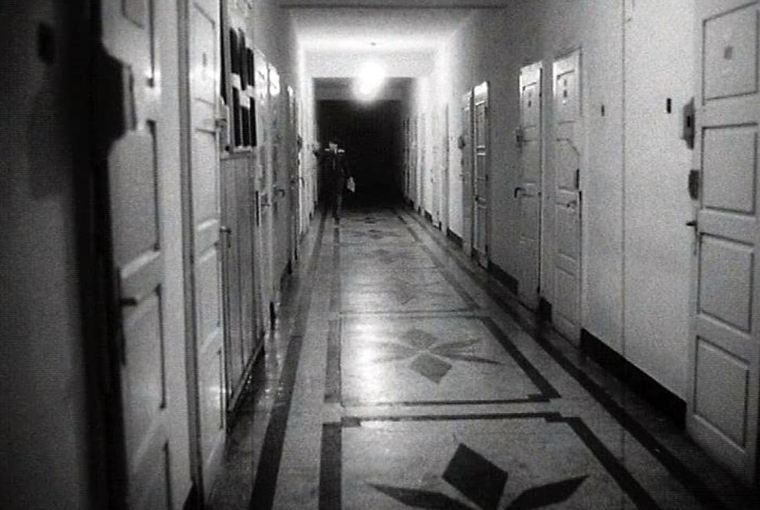

In the late stages of her filmmaking career, Zhelyazkova devoted much of her time to the only women’s prison in Bulgaria. The subjects of her two documentaries shot in 1982 and released in 1990, Lullaby (Na-ni-na) and The Bright and Dark Side of Things (Lice i opako), were women detained for theft, embezzlement, and murder. With her own voice as a solemn narrator, she addresses the complicated web of mistreatment and self-sabotage within which these women live. True to her filmmaking self, Zhelyazkova asks open-ended questions which probe both a prejudiced as well as a compassionate gaze. Instead of opting for an invasive approach bordering on fetishism, her filmmaking style endorses the female voices who were often silenced, not unlike her own. Before turning to this cinéma vérité documentary double bill, I’d like to present its fictional predecessor, which came almost a decade earlier, the revolutionist tragedy called The Last Word (Poslednata Duma, 1973). Looking at these three films as a triptych does not follow the logic of a genealogy, since the films already coexist in a trilateral unity or thematic universe. Usually dealt with separately due to their stylistic and structural differences, this trio belongs to the imprisoned women who were rendered voiceless by self-perpetuating regimes of power.

At large, the 1970s were considered a golden age for Bulgarian cinema, with larger production budgets and more cinema venues to show the larger number of productions. However, it took Binka Zhelyazkova five years to get back to filmmaking after the censorship of her allegorical fable The Tied Up Balloon (1967), which was infamously pulled from the Venice film festival once totalitarian leader Todor Zhivkov was briefed on the film’s (supposedly) decrepit morale. What the regime minded the most, it seems, were political metaphors and emotional ambiguity, both of which are trademarks of Zhelyazkova’s work. In The Last Word, the filmmaker insists on real events, but her expressive use of form and formalist stylization transform a sober reality into a cautionary tale in a manner no less poetic than her prior surrealist feature.

“The Last Word”

In the middle of the sundrenched frame, an elderly woman turns to the camera. Her direct address coincides with the final notes of an uplifting melody that has been travelling across a long opening sequence shot on a beach, carefree and joyful in its setting. Promptly, the woman’s gaze meets the viewer’s eye line with insistent longing. That is, until a blood-red transitional fade cues up an agonizing scream. One silently demanding woman hands it over to another that’s not so tacit; as if taking the cue of this cross-editing, she averts her eyes. These two women, we will learn, used to share a prison cell. One of them will die at the cost of the other’s desire to live.

In The Last Word, six young women share a prison cell that’s now haunted by the cries of a pregnant woman (Tzvetana Maneva) who has no name and is known by way of her occupation: she is a teacher. Or was, before she got convicted for conspiracy with the then illegal resistance movement (the antifascists), and together with her five cellmates, now she waits on death row. “It hurts while we’re giving birth, it hurts while we’re alive, and also when we die,” says one of them as an attempt to ease the teacher’s labor suffering. With a similarly unsparing tone, The Last Word shows its protagonists no mercy, makes no promises for a better future. Yet spending the two-hour runtime intimately exploring these women’s woes and political convictions, does instill in the viewer an alluring sort of confidence in female kinship as a form of existence which endures no matter what. With the noteworthy absence of co-writers, Zhelyazkova scripted the film herself, and her formalistic intuitiveness seeped through the often-aggressive editing style to paint a portrait of a group protagonist – the six female prisoners. This testifies both to her feminist activism, as well as her reverence in front of camaraderie in the face of political oppression as a humanistic value of the highest order.

The film doesn’t simply unfold, it rather oscillates in a dynamic interrelation between present and past, with the prison scenes taking place both during the antifascist persecutions of the 1930s and during a present-day (1970s) memorial for the victims of said persecutions: the notable July 2, observed as the Day of the Fallen (partisans) in the fight for Socialism. In the extended associative collage that is the whole film, these two planes of temporality collapse into each other, and that same collision imbues both parts with nostalgia and repentance, on the one hand, and on the other, with the irreversible determination with which the verdicts were carried out. The effect is merciless. In the film’s beginning, the Student (Dorotea Toncheva) is forced to relive her own death by hanging in a protracted sequence where the shaky camera remains insistently glued to her front-lit face. But little can be read there, on this porcelain field of unknowability. She, too, does not hesitate to break the fourth wall and keep her gaze firmly locked, as the camera tracks her execution path in reverse. When the sequence takes a frantic turn – she runs, she falls, she is caught and brought to the noose with a black cape covering her head – the score follows with a neurotic rise to a crescendo. The sonic peak also introduces an aggressive cut to a mirage of waves violently crashing against resisting cliffs. Similar aquatic interludes punctuate the narrative amidst other significant sequences. These rapid cuts suck the viewer into the protagonist’s emotional depths, lending a hypnotic snapshot before snatching it again to reveal a tragically banal reality. In this case, the guards have played a trick on the Student, cutting off the noose as soon as the chair is pushed from under her feet. A mock hanging, a trialed death – an apt allegory for living under state socialism and, why not, under the patriarchal order.

In another symbolic substitution, the iron chains are presented as a rattle for the baby. The irony never escapes these women who are first bound by ideological belonging, and then by gender. The Last Word can be read as feminist because of its deep investment in female subjectivity, stream of consciousness, and affect-driven associative plot, never stopping short of exposing gender biases on the way. A particularly arresting sequence oversees the women being taken for haircuts in the prison’s courtyard, where a spectacle is then made out of the procedure. Guards are ruthlessly yanking braids and strands of hair, their hands and scissors alike seem to cut through the frame itself, as if the membrane of the screen the film projected upon had to endure this unnecessary demonstration of power. Supposedly de-feminized, the women first cry out until they surrender to silence altogether. But when the men decide to mock them and throw their own hats so they can ‘cover themselves’ as an act of sarcastic pity, communal laughter arises. Caressing each other’s shaven heads, the women are giggling, as if celebrating a secret known only to them in a cathartic revolt. Amidst scenes of rape, torture, and forced interrogations, the women are constantly prompted by men who want to sabotage their partisan bond and disseminate suspicion. Formally, this gender divide is mirrored by the use of light: while the female characters are always illuminated by a front light, the men are seen in low key or shadows. Even when the investigator gets to enact the death sentence, he cannot help but admit that the women’s resistance counts more than the cruelty they are forced to endure by muttering, “The future is yours, but the present belongs to us”.

The only woman-directed film in Cannes’ Main Competition in 1974 was praised as “a sort of hymn to hope and humanity […] with brio, flair, and technical virtuosity” by Variety.2 It won first prize at the Bulgarian Film Festival “Zlatna Roza” and the special ‘Femina’ prize at the Brussels Film Festival in 1976.

“The Bright and Dark Side of Things” and “Lullaby”

Nine years later, Binka Zhelyazkova returned to the theme of imprisonment, but this time as a documentarian. After spending some time with the inmates in the only women’s prison in Bulgaria, which was built only 20 years prior, the filmmaker adopted a verité approach in order to liberate, rather than capture the various stories as told by the inmates. Both The Bright and Dark Side of Things and Lullaby are unflinching, ethically engaged projects that compliment Zhelyazkova’s aspiration for truth-telling, meticulously dressed as formalism.

The Bright and Dark Side of Things opens with a state of anticipation: the date is October 14th, 1981, and marks the 1300-year anniversary of Bulgaria. This occasion, or rather its questionable historiography, pressed into national mythology, has been easily co-opted by the socialist regime to execute an act of benevolence which will be the peg to why the film is made: on the centenary, amnesty will be granted to some of the convicts in the prison.

In a narrative structure similar to that of The Last Word, this film also moves back and forth between a fated day of celebration and the preceding days of interviews with the women inmates. The anniversary in all its pompousness counters the harsh documentary reality, but only hints at the absurdity of the situation. This is not Binka as in The Tied Up Balloon, where the irony is masterfully distilled into allegory and metaphor. No, the documentarian Binka contextualizes her film within the last decade of a regime that has left her desolate and ostracized. There’s an increase in female-perpetrated crime, the narrator (herself) observes. When pondering on the most urgent question, “Why?”, she remains silent – “We can’t say.” The film inhabits a plane of questioning, but these are not rhetorical questions. Instead of handing a simplistic explanation herself, Zhelyazkova presents her film in lieu of an explanation. She values the act of dialogue – even in the form of confession – and that of bearing witness over reasoning and justification.

The film’s politics can be deduced by the representation of the women in prison, even when most of the questions being asked are about their personal histories. The prison walls may hold their stories in, but the environment does not serve merely peripheral functions. Rather, it is a home, a workplace, a master difficult to please. For instance, labor is shown to have at least two meanings (three, if we count the prison pregnancies in Lullaby): one has to do with the undervalued manual labor the women perform in the facility’s sewing factory, another with the arranged marriages which one enters already doomed to slave away. The stories of inmates convicted for embezzlement reveal a cycle of patriarchal violence enacted by and on women. Some mothers-in-law arrange marriages for their sons, effectively ‘buying’ the bride off her parents for a sum, and in turn ask her to work (and steal) until she pays the debt she has involuntarily accrued. The transactional nature of marriage and familial bonds is highlighted by the candid storytelling, which paints the web of a patriarchal order as an unavoidable trap. However, such representation is far from condemning – as would be customary vis-à-vis inmates, especially the Roma characters among Binka’s subjects – but instead plays an important role in providing space for such testimonies. Paying attention to the particularities of such intergenerational violence gets to the core of Zhelyazkova’s concern: can film have a transformative power when people are seen owning up to their own misdoings?

The confessional nature of the monologues is also embedded in the way the women speak, with a mix of more refined, albeit quasi-bureaucratic Bulgarian and colloquialisms, while the lack of local dialect words suggest they’ve acquired a composed sense as a result of being filmed. While this inference may suggest a staged aspect of the interviews, the impression of being calm and collected has more to do with finally claiming ownership of their own stories, and doing so on camera. However, the formal organization of these scenes also suggests that the women yearn to speak out, and that the camera lets them do exactly that, it listens tactfully. Always seen in groups, the speakers take turns in speaking but are never framed in a conventional ‘talking head’ manner. Their faces are, instead, more often obscured than fully shown. The camera thus is a reliable testifier as it unfolds its static long takes, carefully positioned so the bunk bed can obscure the woman’s eyes when she doesn’t want to be spotlit. Others are captured only in profile, and some – with their backs facing the camera. The plasticity of such blocking should be thought of in conjunction with the presence of other female bodies, as the (forced) communal life in prison also reminds us of resilience and female kinship.

As in The Bright and Dark Side of Things, perpetuation of violence is a main concern in the 59-minute Lullaby, which clocks at half the former’s runtime (130’). At first, the camera assumes the viewpoint of a hesitant inmate who spies on the others and therefore keeps its distance. Gradually, it comes closer, approaches women, invites them to speak, and listens. The voice-over is less present here, as the subject matter is more unified. Barbed wire is contrasted with the soft blankets and baby skin, as the film focuses on the children born in prison, a thread which was left unexplored in The Last Word, where the birth of the child was a transformative, but necessary part of life. Here, Zhelyazkova attends to the gap by talking to real mothers and gathering their first person’s stories, while the babies are nonetheless present, but the camera can only caress them from afar, as the cots are secured with bars that allude to a double imprisonment. The camera lingers over faces of both mothers and children, often mismatching sound and image as if a quest to include as much of them as possible cannot be satisfied, as if a frame were not enough, nor is a sound recording: a whole film is not enough to encapsulate the minutiae of emotional trajectories, the nuances of their feelings, and the narrative roles they cast themselves in.

Many of the women interviewed insist they are innocent. Some self-reflexively cast themselves as victims of a regime of power (familial, political) or other forms of injustice, and most of them identify as mistreated women who are lied to, forced to steal, and placed in impossible situations by people they’ve trusted. They are victims, according to the film. But in the same vein, Zhelyazkova also questions the context from which these women are speaking. Sometimes she, as the narrator, challenges them, corrects them, calls them out when they misrepresent the facts about themselves. On one particular occasion, Zhelyazkova resorts to the “I” to share how upset she was by one particular story, that of a woman who was not allowed out of prison to see her toddler whose arms were amputated following an accident. The filmmaker then recounts how she made her way to the house, to see the child for herself, while admitting a certain titillating curiosity. The reality is harsh but in an unexpected way – the boy is healthy and able-bodied. Sparing us a verbal verdict, Zhelyazkova goes back to the mother, recounts to her what she’s seen, and asks her, “Why would you lie?” The transformation which follows is indicative of Zhelyazkova’s conviction as a filmmaker. The women around Bahrie (the mother in question) who have heard all that chime in, offering their own rationalizations and psychological reconstruction of what might have caused this discrepancy between the reality and the fictitious image they had believed up to that point. Bahrie finds herself consoled by her cell mates that she is no liar, telling her that she was scared; that her imagination played a trick on her. Zhelyazkova, narrating, also refuses to believe that this is “the latest scam by a habitual scammer”. She then resorts to a quote by Dostoyevsky, which encapsulates her own humanistic stance, which she never failed to exhibit in all her works, fiction and documentary: “Man is a mystery: if you spend your entire life trying to puzzle it out, then do not say that you have wasted your time.”

References

- 1.Holloway, Ronald. Bulgaria: The Cinema of Poetics. In: Goulding, Daniel J. Post New Wave Cinema in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

- 2.Moskowitz, Gene. “Pictures: Poslednata Douma.’’ In: Variety 275, no. 2 (1974), 26.

Leave a Comment