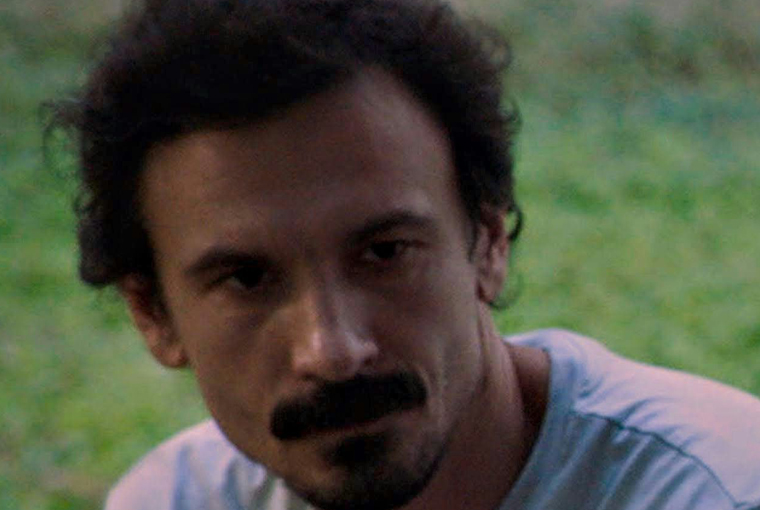

We interviewed Juraj Lerotić at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival (3-13 November 2022), where his feature “A Safe Place” – which was inspired by the death of the filmmaker’s brother – had its Greek premiere. Lerotić discusses his aesthetic choices, and some of the challenges of addressing personal themes through art.

Why did you choose to approach this topic through the cinematic medium? What is unique to audiovisual expression that allowed you to explore this theme in no way other dramatic medium could, say literature or art?

Aside from being a film about love, I think it’s a film about the force of death and the triumph of nature over our efforts. It seems to me that the dramatic form can most accurately represent the silent actions of this force and give the spectator the opportunity to witness the brutal chain of events which the characters face. In my experience, there is nothing sacred about death, on the contrary, it seeps into the reality of the banal. Death exists in these everyday images: in a store, on a sunny street, on the beach. That contradiction was the scariest thing for me. What is characteristic of the film medium, so to speak, is that it accurately and cold-bloodedly captures the reality around us. Any other medium besides film would somehow have to translate that reality into its own language; into a letter, a stroke of a brush or a musical note – which would indirectly reduce the terrifying gap between the presented reality and the horror which unravels inside that reality.

Your film deals with a very difficult subject, that of suicide, which is still taboo in most societies. You have chosen to represent this subject through a unique formalist approach, somewhere between oneirism and realist minimalism, which works both to disorient and bring the spectator closer to dramatic situations. How did your film’s style help you convey this story and create the necessary atmosphere?

We don’t know much about suicide, unfortunately, and we know even less about death itself. That is why it’s perhaps most honest to leave room for many versions of the truth. That is why I chose oneirism and an open form, and that’s why there is minimalism in the film – which tends to suggest and inspire more than showing and preaching. We thought that the narrative was strong enough, that the direction does not need to highlight it, especially not the part which concerns the emotional world of the characters. In addition, psychology has taught us that during extremely stressful situations, we don’t actually feel anything nor cry, we are somehow not in touch with ourselves. We are in a kind of weightless state, we perceive ourselves as an object that is subjected to violence. That’s why we moved stylistically towards the presence of a camera that silently observes and catalogues events without commenting on them. We showed the most dramatic situations in wide shots, thus creating the feeling that the characters within the frame are delivered to something bigger than themselves. We left space for the unknown, for what cannot be shown. It also seemed important to us to allow nature to show its other side – we shot during spring, which is the most vital and beautiful season in many people’s eyes.

The most striking scene is the intimate and open imaginary conversation between the two brothers in the hospital around the question of suicide. It is very sensitive in dealing with the feelings of trauma, incomprehension, and loss of a loved one. Could you please comment on this scene?

When writing, I tried to take into account that the form should somehow reflect the content, that is, the trauma. The scene in which the fourth wall is broken disrupts the cinematic form as suddenly as the trauma disrupts the life of the protagonist. It seems to me that in this way, both the form and the content ask the same questions, they create the same emotion.

On the other hand, there is also a lot of love in the mentioned scene, which the viewer can return to after watching the film, and find some consolation, in a similar way that I can return to my brother in my mind. It seemed important to have such a scene, but I didn’t want to show it at, for example, the end of the film, and “escape” toward a happy ending. Such an approach would not reflect the complexity that trauma has in real life.

I wrote the script one year after my brother’s death. I often wondered during the writing process what he would say about me making a film inspired by his death. I often “talked” with “him” about it. In the end, it seemed to me that these thoughts should not be hidden, that in a way, it is truthful and right that a fragment of these thoughts should be present in the film. In the aforementioned scene, the viewer, in addition to the fictional character, suddenly meets me, the author who created the film and actually experienced what is being shown. Discovering this, the film somehow begins to overflow the boundaries of the fictional work, and for some viewers, it becomes a film about survival, about what we can do with trauma, which is usually embarrassing and forces the traumatized to hide.

When watching the film, one gets the impression that every single detail within the frame has a purpose, nothing is left to chance. Similarly with the use of sound, the interplay between moments of “silence” and actors’ voices, and other ambient sounds, are so carefully composed to counterpoint, accentuate, or distort the viewed and felt reality from each character’s perspective. Could you please explain how you worked with sound and how important it was to avoid making recourse to a soundtrack and non-diegetic music?

Conventional music would seem somewhat invasive in a film like this, like a commentary on events in front of which a person intuitively remains silent. I think that the camera in the film also witnesses events rather than commenting on them. We also wanted to approach the sound in this way. Eventually, the film’s antagonist – death, in this case, –, as is often the case in life, comes very silently, un-orchestrated. Trying to use the sounds surrounding the characters to create a suggestive but less intrusive soundscape, also seemed more appropriate to the editor, Marko Ferković, and the sound designer, Julij Zornik.

The technology allows you to modulate recorded sounds. Record the sound of the air conditioner, drop it 3 octaves lower, add the sound of the refrigerator to it – put those two sounds in some relationship, and you create a double voice or a chord that can have almost minor or major qualities, sound harmonious or disturbingly dissonant. That way you create atmospheres; a dense mass of noises that seem oppressive or the complete opposite – a silence that creates a feeling as if anything could happen. You get to precision and simplicity through this process – in the end you feel that one sudden scream of a child between the buildings traces the entire space more accurately than the general atmosphere of the city, the murmur of passers-by and the like.

The film slowly builds a powerful and magnetic dynamic between the family of three, the two brothers and the mother. You play the leading role in the film alongside fellow actor Goran Marković. Could you tell us about your choice to take the leading role and how you worked together with your fellow actors to achieve such poignant performances?

It wasn’t my intention to act in the film. But during casting, I was mostly alone with the actors, rehearsing lines. As I viewed and discussed some of the rehearsal recordings with my colleagues, they encouraged me to try to record myself more directly. The final decision to play the older brother was not easy to make because it blurs the line between fiction and reality even more. Which is good for the film, but psychologically challenging for me.

On the other hand, acting in the film gave me an additional advantage in terms of communicating with the actors, in a way that is less verbal and rational, and more intuitive. The way I play a scene reflects on the performance of other actors. It’s like an exchange of ideas similar to a band playing together. Otherwise, as a director, you are deprived of that aspect. You can only talk before and after the scene, that is, “create the scene from the outside”, but you do not participate in its creation.

As for the acting style itself, we tried to get closer to what is called “acting in one’s own name”. Where the actors are actually themselves but in the circumstances of the character they play. Those who liked the acting style in the film described it as subtle and subdued, and, at the same time, articulate and alive. That style of acting has to be discovered together and believed in. Because, like all minimalism, it can end up in expressionlessness, in something that does not reach the viewer.

In Thessaloniki, you and I had already briefly discussed the importance of developing and writing narrative structures based on the needs of a particular story. Could you explain how you developed and worked on the script of Safe Place?

I like Adorno’s thesis that form should really be crystallized content. After I had the content, I began to work on the dramatic form which would best suit it. A traumatic situation – a sudden suicide attempt – opens up a gap in the family’s everyday life. The meta-filmic conversation between the brothers in the hospital is an attempt to transfer the gap out of content and into the form – the architecture of the script. The idea is to somehow shake, to damage the text itself – the homogeneity of the action and the time in which it takes place. Not in more than one place, because by repeating that approach, it would cease to be a wound and instead become part of the script’s fabric.

I think it’s also a film about asymmetry; examples of the disproportion between the energy invested to help someone and the end result. It seemed logical that the form also had to have something asymmetric, wobbly. Through the writing process, I tried to find the cleanest and most direct way of throwing the form off balance in some way.

In addition, I think that the biggest challenge for me was to make a film that emotionally engages the viewer without the characters themselves constantly being emotional. I have a very vivid memory of the period in which I tried to help my brother. Emotions were suppressed, everything was focused on finding a solution. I wanted the film to be truthful in that regard, not to decorate the characters with emotions that people actually only start to feel afterwards.

Stylistically, and in other ways, your film also brings to mind the aesthetics of the Romanian New Wave. Were you influenced by any particular films or filmmakers when making the film?

It may sound pretentious, but as you have noted earlier there is an oneiric dimension to the film, which is not characteristic of the Romanian New Wave. We were more inspired by the authors which Paul Schrader classifies as transcendental, and by exponents of “slow cinema”, for example Robert Bresson, Yasujirō Ozu, Tsai Ming-Liang.

What we tried to avoid is the mannerism of slow cinema, for example the doctrinal renunciation of editing, the insistence on the long shot as if it were a sports discipline – as a result of which, in the end, one’s radical approach becomes bizarrely predictable, dysfunctional and conservative.

By simplifying reality, by introducing somewhat stylized clean surfaces, Edward Hopper tried to achieve “realistic art from which fantasy can grow”. I think that cinematographer Marko Brdar, set designer Jana Plečaš and I were aiming for that. Some austerity that is not an end in itself, but which serves the imagination.

On the one hand, your film is highly personal, dealing with family trauma, and on the other hand, it touches upon broader societal issues, like the dysfunctionality and bureaucracy of the healthcare system and mental health. Was the film meant as a critique of the current state of the healthcare system in Croatia? What social impact did you hope the film would have?

A lot of people wrote much about the film from exactly that critical point of view – connecting it to their own bad experiences in the health care system. I doubt that my film will lead to any significant change. This requires political will. In Croatia, the Strategic Framework for the Development of Mental Health was adopted at the end of 2022, which we had been waiting for since 2016, when the old framework ceased to be valid, and it is uncertain how long it will take to implement the plans and to secure the funds. Of course, this is then reflected, among other things, in the absence of prevention, in the reduced capacity in our psychiatric hospitals, etc.

I think that the film criticizes the health care system but tries not to fall into the trap of being a poster child for the cause. Safe Place primarily confronts us with the elusiveness of mental illness, which is often romanticized through films, with the decisions that are placed on close family members of the affected person, and with the disturbing powerlessness of the patient, the family and ultimately the system and science before the destructive power of mental illness. In an age when it is assumed that every phenomenon can be rationalized, explained, and rehabilitated through one of the many advertised methods, mental illness, like birth or death, points to the mystery of human nature and the painful limitations of our cognitive apparatus.

Thank You for the interview.

Leave a Comment