The Future of an Illusion

Andrey A. Tarkovsky’s A Cinema Prayer (2019)

Vol. 106 (Summer 2020) by Isabel Jacobs

There are few directors haunting world cinema as persistently as Russian director-legend Andrey Tarkovsky. The British Film Institute’s magazine Sight & Sound doesn’t hesitate to include three films by Tarkovsky in its 2020 list of the 100 best movies ever made. For cinephiles around the world, Tarkovsky is the uncontested master of meditative and (sometimes painfully) slow arthouse cinema. With films like Mirror (1975) or The Sacrifice (1986), Tarkovsky also gained reputation as a visionary guru for those who remain spiritually dissatisfied by 21st century capitalism. The Moscow-based studio Hype Film just announced that they are planning a new TV series about Tarkovsky’s life, written and directed by Kirill Serebrennikov. In a nutshell: Tarkovsky is an icon of contemporary culture.

Against this backdrop A Cinema Prayer (2019), a new documentary directed by Tarkovsky’s son Andrey A. Tarkovsky, doesn’t come as a big surprise. Even less so as this isn’t Andrey’s first tribute to his father. Already in 1996, together with Alexey Naydenov, he had realized Andrey Tarkovsky: A Recollection, an intimate portrait about his father’s last days seen through his own eyes. A Cinema Prayer adapts the same principle. The viewer is guided through the feature length documentary only by the master’s voice. Instead of relying on experts, family members and friends, Tarkovsky is the omniscient narrator of his own life.

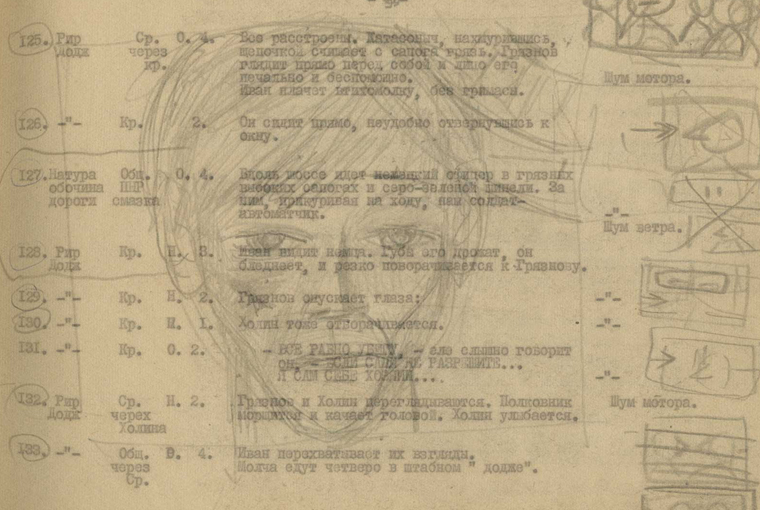

The documentary is a meticulous symphony of film excerpts, audio material, photographs, poems, diaries, screenplays, working notes, music, polaroids, drawings, and fragments from other documentaries. Most material comes from Tarkovsky’s archives in his former apartment, today part of The Andrey Tarkovsky International Institute which is managed by Andrey A. Tarkovsky. Andrey A. was a teenager when his father died of terminal lung cancer in 1986, just one year after he shot his last film The Sacrifice in Sweden. While not offering many new insights, A Cinema Prayer is arguably the ultimate tribute to Tarkovsky. It’s an Italian-Russian-Swedish co-production, and the editor is none other than Michał Leszczyłowski, who had worked with Tarkovsky on The Sacrifice.

After its release, A Cinema Prayer was shown at the Venice Film Festival 2019 and nominated for the Venezia Classici Award for Best Documentary on Cinema. In this context, Andrey A. Tarkovsky gives us insight into his obsession with his father (“the great artist, great man and life mentor”). The director announces that the documentary explains the “Tarkovsky phenomenon” from a new perspective: “What did Tarkovsky himself think about it? Where did he get his inspiration?” And finally, it promises nothing less than Tarkovsky’s resurrection: “Would it be possible, more than thirty years after his death, to hear again the voice of the director?” We know the same, slightly self-indulgent obsession with the absent father from Tarkovsky himself. His father Arseny’s poetry had had a huge influence on his films that are driven by the nostalgic quest for a lost childhood. This genealogy of longing for the father finds its culmination in A Cinema Prayer.

In eight chapters with titles like “Andrey’s Passion”, “At the Verge of Apocalype” or “Eternal Return”, a loose story is woven around his films and biography, guided by Tarkovsky’s narration in a voiceover. The title, “A Cinema Prayer”, already suggests a certain focus on Tarkovsky’s relation to religion: through the eyes of his son, Tarkovsky appears as a mystical prophet revealing his invocations to the viewers. “True images,” Tarkovsky later tells us, “can only be created if cinema is like a prayer, addressed and dedicated to God.” For Tarkovsky, the meaning of art is prayer and worship to God. Both main themes of the documentary, Tarkovsky’s fascination with childhood and his religious philosophy, can be fused in Tarkovsky’s claim that we have to “believe in our roots.” The idea of devotion to the past — the father — is not only a key to Tarkovsky’s work, but also the driving force of his son’s documentary.

The first chapter “Bright, Bright Day” opens with one of the meditative shots we know all too well from Tarkovsky himself. Then we zoom into childhood photographs of the young Tarkovsky with his father Arseny in the garden, accompanied by Arseny’s voice reading a poem that had initially been recorded for Mirror, but was never used: “Never again have I been / As happy as then. / There can be no returning, / Nor has it been given / To tell what perfect joy / Filled that garden heaven.” We are immediately on the scene of a typical Tarkovsky tableau, a nostalgic reminiscence of a childhood in deep union with nature.

Tarkovsky later tells us that “children somehow connect our world with another, transcendental one. For they haven’t lost this connection, they will soon, but haven’t yet.” In the same spirit, we are now seeing familiar excerpts from Mirror which show the boy waking up, then a cut, and the grown-up director speaks about the impact of childhood on his work: “An artist feeds from his childhood for his entire life. The traits of his childhood determine the nature of his art.” Another cut, it’s war time and his father is wearing a uniform, the soundtrack is a piece of St. Matthew Passion by Bach, Tarkovsky’s favorite composer. Is this really going to continue like that for the next one and a half hours?

In an interview with Cineuropa, Andrey A. says about his father’s relation to his work: “He wasn’t that eager to talk about it. He didn’t even like his films!” When watching A Cinema Prayer, this is very difficult to believe. We see endless sequences of archival footage showing Tarkovsky, mainly sitting motionless in front of the camera, sometimes silent, absorbed into thoughts and gazing towards the sky, then listening to the sound of his own voice, while classical music is playing in the background. What is he doing there? Are we witnessing his spiritual awakening?

In tireless monologues, Tarkovsky soliloquizes and is very eager to share his philosophical insights with everyone — although few have access to them, as we then find out. In any case not film critics, but “simple” people. In one wonderful scene, Tarkovsky tells an anecdote about the first screening of Mirror, when many film critics were present, who “as usual didn’t understand anything.” After the screening he talks to the cleaning woman, that “simple lady” who “didn’t even go through primary school,” and yet she was the only one who completely understood his film. It’s painful to see Tarkovsky’s level of detachment from reality and the didactic arrogance that comes with it.

We already know this rather unpleasant side from other Tarkovsky documentaries, especially Donatella Baglivo’s Cinema Is A Mosaic Made Up Of Time (1984). Again, in A Cinema Prayer, Tarkovsky’s seriousness doesn’t leave any space for irony and lightness, instead the viewer feels left behind with prefabricated wisdoms like, “Freedom is one’s inner freedom, the spiritual freedom of a person.” Even though the heavy tone overshadows the whole documentary, there are a few very interesting moments which are worth mentioning. One of the highlights is certainly the journey to Tarkovsky’s country house in Myasnoe, near Moscow, where he lived with his second wife and his son’s mother Larisa Pavlovna. What looks like a mix of archival and new footage, throws us immediately into Tarkovsky’s famous childhood myth.

We can’t but perceive Myasnoe’s mesmerizing landscape and the house already through the lens of Mirror, suddenly realizing how imagination, reality and memory are completely intertwined in Tarkovsky’s films. This house, the director tells us, “makes me a human being.” Here the documentary loses its tendency to abstract mystification and we get closer to the person Tarkovsky and the surroundings that shaped his personal life: “I sit down on the steps and cinema begins. Not that type of cinema with a plot, but the one that is real cinema to me. It’s wonderful!” This scene is a way more personal and touching insight into Tarkovsky’s process of creation out of direct impression of the landscape around him than any random ruminations about the spiritual essence of art.

Another strong passage tells the story of how Tarkovsky develops his notion of poetic cinema from experiencing difficulties when editing Mirror. Realizing that the film would never find the form initially charted in the script, Tarkovsky felt forced to change the whole dramaturgy. The documentary elegantly shows how it was exactly this “failure” of literary narration that enabled Tarkovsky to conceptualize cinema as metaphysical poetry. We hear Tarkovsky explaining: “Cinema in its essence, its predominance, its figurative composition, is poetic, for it does not need to be literal, nor to abide by the sequential nature commonly adopted in dramaturgy.” Instead, cinema “is the only art that literally freezes time.” Cinema is “like a time matrix.”

The documentary then links this notion of poetic cinema back to Tarkovsky’s fascination with icon painting. Both in icon painting and cinema, Tarkovksy claims, the image can’t be deciphered, only its “pure metaphysics.” In contrast to the didactic tone of the documentary itself, Tarkovsky suggests here that a film is not a charade or a symbol. A film can’t be resolved like a puzzle, because there is no solution. This openness of interpretation is something A Cinema Prayer definitely lacks. The documentary’s biggest flaw is not the absence of a story, but rather that the director tells, shows and explains too much. There is absolutely no space for the viewers’ imagination and freedom to come to their own conclusions.

Beyond its own aims, A Cinema Prayer is an interesting case study in analyzing contemporary Russia’s ideological constellations. We painfully observe how Tarkovsky’s conservative elitism, a variety of dissident opposition in Soviet times, finds itself in today’s world order in strange alignment with Russia’s neo-conservative, increasingly repressive cultural politics. Through the voice of Tarkovsky we hear all too familiar tropes of Russia as the chosen country of spiritual rebirth, the salvation of mankind and the preservation of traditional values. Or, in Tarkovsky’s words, towards the end of the documentary: “If someone should ask me, where do I posit hope for the future, I would say only in Russia, despite everything. A civilization without spirituality, without belief in the immortality of the human soul, is no more than a gathering of animals, it no longer is a civilization, it’s already the end, the decline. That’s why I see in Russia far more signs of spiritual reborn than here, in the free West.”

After one tiring hour of A Cinema Prayer, the narrative structure loses its drive and falls apart into a rather random collage of souvenirs, images and monologues. The last thirty minutes are completely unstructured and the film fades out with a five-minute slideshow with photographs of Tarkovsky, while Bach’s Mass in B minor plays in the background. Unfortunately, A Cinema Prayer doesn’t really bring us close to what made Tarkovsky the filmmaker he was, but rather adds to the existing cult around Tarkovsky as the visionary prophet of Russian cinema. Even when we hear him talking about deeply existential difficulties like being exiled, parted from his homeland and torn between two cultures, we don’t really gain much insight into the person Tarkovsky, his emotions and his personal life. He remains an abstract giant of a filmmaker who happens to be the father of the documentary’s director.

if you want to hate Tarkovsky there is a simple way of doing it; just say it openly giving your justification for that as a critique.. otherwise just like you did here you need to hide it under bitter and smartass words like: “We painfully observe how Tarkovsky’s conservative elitism, a variety of dissident opposition in Soviet times, finds itself in today’s world order in strange alignment with Russia’s neo-conservative, increasingly repressive cultural politics.” that only confess how you love to hate him as an epitome of encoded narrow mindedness of your own conservatism.. it is sad that Tarkovsky’s sense and sensibility totally bypassed you which still shines under his thick bygone idealism and orthodox identity together with his feeling, dreaming and pondering camera eye which is unprecedented in all of film history..

so curtains are still iron on the east side of Europe eh ?.. good for you!!!…