Grieving the Lives of Others

Bobo Jelčić’s A Stranger (2013) & Ognjen Glavonić’s Depth Two (2016)

Vol. 64 (April 2016) by Moritz Pfeifer

One way to think about “others” is to ask whose lives “we” consider valuable, whose lives we grieve and whose lives we do not grieve. Some acts of mourning draw thousands of people to public ceremonies in which they express their sorrow for human loss. Others are held secretly and would provoke shame or outrage if they were to take place in the public sphere.

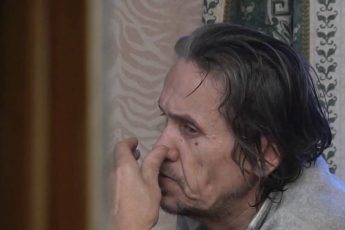

How difficult it is to grieve for someone whose life has been made ungrievable is at the center of Bosnian director Bobo Jelčić’ debut feature A Stranger. The film is set almost two decades after the war, but ethnic tensions are still prevalent. Slavko (Bogdan Diklić) is a Catholic and invited to attend the funeral of a longtime friend whose family is Muslim. Afraid to go to the funeral for fear of betraying his ethno-religious roots, he has to face a painful dilemma. If he avoids the funeral, he loses his face in front of his friends and family. Going to the funeral forces him to publicly grieve for a Muslim’s life.

A cover-up operation that happened in the aftermath of the Kosovo War, shows that conferring legitimacy on loss can be a powerful ideological weapon. In 2001 a fisherman accidentally found 86 Albanian corpses in a refrigerator truck that had been dumped into the Danube close to the Eastern Serbian village of Tekija. The incident set in motion a cruel scheme to dispose of the bodies that involved high officials of the Serbian interior ministry. The truck was secretly transported to a firing range at a police training center in Petrovo Selo, near Kladovo, where it was blown up. One of the victim’s children said of the incident that “it was like another murder for us”.1 The story of this secret operation, also known as Depth Two, is at the center of Ognjen Glavonić’s homonymous film. Glavonić uses oral testimonials as voiceovers over mood shots that are loosely connected to the different crime scenes of the operation: rivers, roads and ruins. Denying the viewer an image of the victims reflects the impossibility to remember them. It is a cinematographic metaphor for their “second death” — they cannot be mourned. “No body, no crime” reads a diary entry of the Albanians by former assistant interior minister Obrad Stevanović, a close associate of Milosević, who had to decide what to do with the corpses.

Even though the death in A Stranger takes place long after the war and was not the result of ethnic cleansing, it also focuses on social norms that make it impossible to recognize the loss of those whom society sees as “others”. Both films are deeply Antigonean stories, where the proper burial of state enemies is prohibited by law. There is a cruel paradox at stake here: how can something that never had a right to exist, be recognized as a loss?

Depth Two thinks that it can’t. Through its form it offers what film scholar Gertrud Koch once called “an image of the unimaginable”.2 We never see the truck with the corpses but have to imagine what happened ourselves. This strategy has become so widespread that trauma theorists such as Michael Rothberg have regarded it as an essential development in the narrative history of all traumatic experiences. According to Rothberg, trauma narratives thus first seek strategies for referring to and documenting the traumatic event; then they question their ability to document the event transparently; and lastly they acknowledge that all this documenting and questioning may be instrumental to economic and political conditions.3 Depth Two is clearly in the second phase of this process. In the words of the director: “it is really important that my colleagues, the filmmakers from the ex-Yugoslav countries problematize, dissect and question what is, and what constitutes our recent history.”4 The film questions its own power to grieve for victims whose experience of living an ungrievable life was constitutive of their victimhood. The absence of images in the film bears witness to that which cannot be grieved.

A Stranger comes closer to Rothberg’s first phase of realistic documentation. Through meticulous details of everyday life, it shows how firmly the inability to mourn for “others” is entrenched in the segregated societies of contemporary Bosnia and Herzegovina. The film takes place in the picturesque town of Mostar, whose Muslim and Catholic inhabitants are separated by the Neretva river that flows through the city. Privately, Slatko tells his wife that his deceased friend “was family to him”. But like Antigone, he is forced to protect his public image by denying this self-proclaimed kinship. Thus, when his neighbor Milan (Vinko Kraljevic) asks him about the funeral, Slavko replies “what funeral?”, as if he had not heard of his friend’s death. Jelčić has a background as a theater director, but his hero, unlike Antigone, does not chose to defy the social norm. Opting for realism, the director has Slavko clandestinely attend the funeral. The cowardly compromise protects his public image as a tough Catholic while allowing him to show his private entourage what a good friend he was.

Depth Two may be one step ahead of A Stranger for trauma theorists. But this certainly does not make the film more “advanced” than the other. In fact, anticipating Rothberg’s third step of economic and political instrumentalization, one may ask whether Glavonić’ “unimaginability” dictate simply feeds into the hands of Europe’s ever growing memory industry, which is now intellectually mature enough to expect films not to “cater to voyeuristic appetites and perpetuate images of black victimization”, as Susan Sontag once put it in a highly influential text.5 Voyeurism may evolve though. To her credit, Sontag could not have imagined that even the most sophistically distantiated portraits are not immune to voyeurism. Alas, spectators today may still drool over the refined renditions of the likes of Claude Lanzman who do not even give them one frame of a victimization.

A Stranger, focusing on today’s repercussions of the past and only indirectly on the representation of victims, does not have this problem. And yet its minimalistically suggestive observations on the seemliness of religious prejudice, ethnocentrism, racism, “othering”, or call it what you may, could very well serve as an example for films like Depth Two, in which any efforts of emotionally understanding what happened are ruled out by a self-imposed aniconism whose intellectual merit lies in the past.

Leave a Comment