Collective Struggles

Srđan Kovačević’s Factory to the Workers (Tvornice Radnicima, 2021)

Vol. 117 (September 2021) by Zoe Aiano

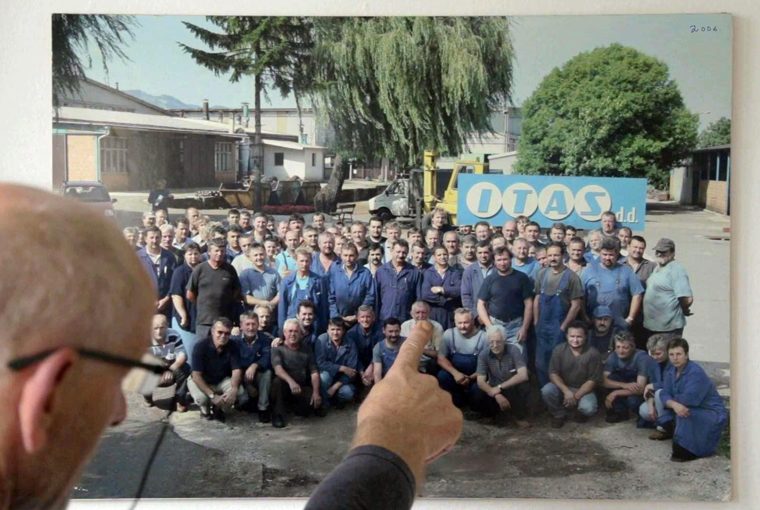

As the only worker-owned factory currently existing in the post-socialist Balkans, ITAS in Croatia bears the heavy burden of proving this structure of organization to actually be viable. Inevitably, however, the pressures of capitalism have not made this transition easy, and it isn’t quite the poster child it’s made out to be. In his documentary Factory to the Workers, director Srđan Kovačević spent five years following the progress of the struggle for self-sufficiency.

From the outset, the obstacles are made very explicit. The workers may control the means of production, but the means of production aren’t very good. The machinery is outdated, deliveries run late, and tensions run high. Nevertheless, there initially appears to be some degree of optimism, as a pretty mural is painted on the back wall and foreigners even come to learn more about how the factory functions in practice.

It soon becomes clear, however, that the major threat to its sustainable operation is generational (in)difference. As Varga, the charismatic figurehead of the old guard, points out in a memorable scene, almost all those involved in the takeover in 2005 are either dead or retired. With ITAS failing to turn a profit and wages constantly in arrears, all the proponents of the current model have to offer the incomers is ideology. For their part, the only thing the youth have on their minds is stability. Promises of shares mean very little to them, they just want to get paid. Worse still, there is a very real risk of apprentices entering the company and then taking their newly learned abilities to a private firm, leading to a potential skill shortage. Nevertheless, despite all these complications, manufacture grinds on.

In tracing these vicissitudes, the film manages to tread a careful line, not over-explaining to the point of drowning the narrative in complicated discourse, yet also not dumbing anything down or over-simplifying. Discussion of horizontal vs. vertical governance are there for those who are into that kind of thing, but the human interest of the characters is also compelling enough for those who aren’t. The shooting style is very classically observational, yet immaculately handled and clearly indicative of a high degree of intimacy between the filmmaker and the protagonists. This is also evidenced by several emotionally charged scenes, such as the disgraced departure of the deposed director, which would likely have been denied to anyone less established within the premises. Likewise, when Varga inevitably rises to power and fails to live up to his promises, his comrades pull no punches in their criticism of him, despite the presence of the camera. The inclusion of such moments also testifies to clear commitment to honesty on the part of the director, who could easily have edited the story arcs to make his characters more bluntly positive or negative but chose to depict them in their full complexity.

The question of audience for a film like this is an interesting one. The film ends with the factory in mid-crisis, with the prospects looking bleak. Clearly, then, it isn’t a straightforward case of leftist propaganda, nor a didactic explanation of how to achieve self-governance in the workplace. Nevertheless, it is obviously framed from a standpoint that wants to believe in this structural system – the viewers are supposed to be rooting for the workers – and the film positions collective ownership as an intrinsic good to be striven for, and its complexities to be overcome, rather than trying to convince anybody of it. It will remain to be seen whether audiences without a pre-existing interest in labor organization are converted to the cause, but at least they should leave the screening better informed about the kind of issues at stake.

One of the film’s biggest potential legacies is something not shown on screen at all, except for briefly at the beginning, as an opening text card reveals Kovačević’s intention to share any profits of the film with the workers themselves. Leaving aside the separate issue of whether a niche documentary is actually capable of producing any profit, the decision not only to implement but also publicize this kind of an arrangement is indicative first of all of the filmmaker’s commitment to acting on his own political stance, but also of an interest in inciting others to do the same. Indeed, the issue of payment for documentary protagonists remains taboo but deserving of debate. If a film is considered as a commodity, surely the people being filmed, who are indispensable within an observational documentary, deserve to be compensated in some way. For a film dealing explicitly with workers’ rights and division of profit and labor, it seems especially important to address this and hopefully this gesture will set a precedent.

Leave a Comment