The Illusionist

The Magic Performances of Multimedia Artist Ivan Ladislav Galeta

Vol. 26 (February 2013) by Moritz Pfeifer

Last year in October, the Croatian multimedia-artist Ivan Ladislav Galeta was invited to the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The screening of his films there was part of a series on Croatian experimental cinema.

For a film screening, it was quite an unusual event. A large blackboard stood in front of the screen which had a magic square drawn on it. As the lights dimmed down, Galeta stood up from the front row and walked towards the blackboard. Galeta is a short man in his sixties. He was well dressed, wearing a waistcoat, and with his shiny bald head and his mustache, he looked a bit like Dr. Phil. He addressed himself to the audience like a school-master, calmly asking questions about the meaning of the numbers and then explained the maths. But Galeta is really more of a mystic, than a mathematician. He closed his introduction with conjectures about the coexistence of order and chaos, appealing to the human ability to find meaning and truth in the lawlessness of nature.

In retrospect this seems like a useful definition of his work. Galeta is a master of making sense out of nothing, and inversely, he also likes to point out that the things that we think make sense are really nothing. His first film – Two Times in one Space (1976/1984) – shows a family at breakfast. The film is superposed by a copy of the same film, so that when one of the characters gets up, he’ll repeat the same movement a couple of seconds later. Generally, Galeta seems to want to tell us that the movements we see on screen are not in sync with the time that we, as an audience, often imagine them to take place in. There are ghosts walking around in this seemingly banal film. This becomes especially funny, when a man jumps from the balcony across the street of the apartment, and seconds later – as if in afterthought – jumps again. We have accustomed ourselves to certain rules when watching movies, for example, we accept to believe that someone can kill himself only once, although we know that that person didn’t really die, and that we could always rewind and see the scene again. But we tend to forget these things for the sake of illusion, because consciously being aware of them would probably ruin the experience.

Galeta seems to have a love-hate relationship with illusion. In another film – Water Pulu (1987/1988) – he also plays with film conventions, this time of recording a sports match. If you didn’t know that this film was initially a water polo final between France and Croatia, you might think it has more resemblance to a Monet painting. Indeed, there is an orange circle in the middle of the screen, surrounded by blurred blue tones, much like in the French artist’s famous Soleil Levant. But the orange circle is the ball of the game, and the shades of blue are the swimming pool. Galeta just edited the film in a way, that the ball would always be in the middle of the screen. The result looks…well…experimental. But if you think about it, Galeta’s version, is much closer to how we actually would watch a game in real life. We follow the ball, and our eyes go through a considerable amount of effort to make the ball the center of our attention. In real life, the static long shots that were custom in the 1980s, when Galeta shot the film, don’t exist. They’re illusions. Like Two Times in One Space, this film makes us aware of how we are fooled into believing that an experience is real, when it is completely artificial. And inversely, once we try to imitate reality, it ends up completely artificial.

Most of Galeta’s film career deals with varieties of this problem. Other films that were screened that evening, like Wal (I) Zen (1977/1989) or Piramidas (1972-1984) ask similar questions about the illusions of film. But since the millennium, Galeta officially declared that he will no longer make art, thus joining the modest community of retired artists. He now travels the world explaining his oeuvre to curious audiences on festivals, and in museums. The blackboard is a helpful tool to Galeta, but he also uses intricate PowerPoint presentations to analyze his own work. At the end of our screening, he stood up again to ask whether anyone cared to see a presentation that would give some insight into his work. By that time, some people had already sneaked out of the theater, but most people were patient and stayed to listen to what he called “some explanatory comments.”

What followed was at least as puzzling as his films. Galeta’s presentation focused on his last film called Piramidas. The film basically follows a train track, while the camera rotates in 45°, at an ever increasing speed until it reaches a zero-point, and the whole trajectory goes backwards to the starting point. So much could have gone without further explanation. Galeta’s own analysis revealed that the film is a mathematical maze. The camera rotates in precise time-intervals, so that it represents the movements of a labyrinth, like this: ![]() The inspiration comes from the Polish amateur artist Wacław Szpakowski, who lived in the beginning of the twentieth century, and whose meticulous maze drawings Galeta included in his presentation. After several more explanations on Maya labyrinths, medieval semiotics, and color theory – that was also supposed to be treated in the film –, one cannot avoid thinking of blackboard and the magic square: there is a meaning behind chaos.

The inspiration comes from the Polish amateur artist Wacław Szpakowski, who lived in the beginning of the twentieth century, and whose meticulous maze drawings Galeta included in his presentation. After several more explanations on Maya labyrinths, medieval semiotics, and color theory – that was also supposed to be treated in the film –, one cannot avoid thinking of blackboard and the magic square: there is a meaning behind chaos.

It appears to me that Galeta’s explanations are more a part of his artwork than about it. Indeed, Galeta doesn’t seem to have retired at all. He just changed his form of expression. His explanations are performances. As such they continue the themes that were already present in his films – making people aware of their beliefs and illusions. If his films pointed at our readiness to accept cinematographic conventions, his performances seem to point at our readiness to accept interpretative conventions. Above all, his performances mock our need for explanations. None of his explanations are really illuminating, but it seems that everyone in the theater accepted them as quasi-scientific truths. Like the magic circle, Galeta’s analysis of his own artwork tries to make sense out of chaos. But art, unlike math, does not follow universal rules, and it wouldn’t make sense for someone who is so obsessed with pointing at the senselessness of pseudo-rules (like the ones propagated by conventional cinema) to seriously believe in his own set of rules.

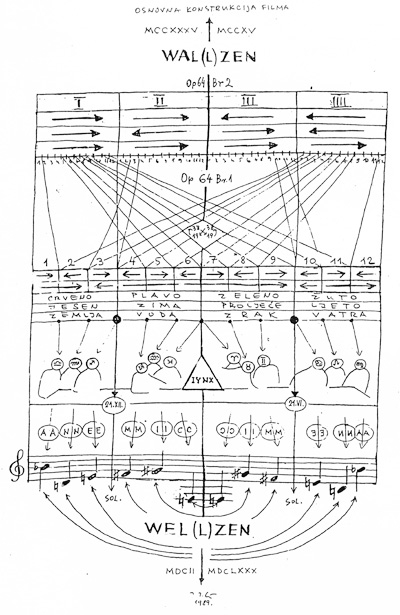

When we met Galeta a couple of days later, he would do a similar performative explanation of his film Wal (I) Zen (1977/1989). Before he started his analysis, we knew from seeing Wal (I) Zen that it was a film about a pianist playing a Chopin waltz, and that Galeta made him play the waltz backwards and then rewinded the recording, so that it sounded like the real waltz. Again, this film shows that the things that we usually take for granted are not like they seem. But Galeta’s interpretation of the work on the next day made unexpected references to da Vinci’s Last Supper. He also told us that he included parts of Schoenberg’s twelve tone technique in the film, and that he set the whole thing up according to precise mathematical principles. The editing of sound and film according to these calculations must have taken him ages. While speaking, he drew the concept on a sheet of paper and his illustration looked like this:

This can hardly be called an explanatory comment. It’s more like a meta-description or an artwork of its own right. The funny thing about it is that it really doesn’t explain anything. But what would motivate Galeta to do these performances?

Maybe Galeta wants to imitate the artspeak of curators and art critiques in his performances, who try to make sense of art but often end up describing it in a coded, almost incomprehensibly complicated way. Galeta’s performance had much of the pseudo-professional gibberish that can be heard on conferences, and read in the booklets accompanying art shows. Ironically, the few articles written about Galeta’s work fail to see this. Instead, they take his explanations seriously, and don’t doubt their authority as interpretative keys. Try to make sense of this “explanation” of Galeta’s film Two Times in one Space by the art critic Miklós Peternák:

A real struggle is going on here in this flawlessly-repeated far niente. The struggle of the εἶδος, the sight or shape itself, and its εἴδωλον, the the [sic!] corresponding figure in the afterlife to become an εἰκών – an image or representation.

I wrote about this kind of jargon in our focus on Romanian video-art, saying that it has more similarities with art than with information. Many critics substitute matter-of-fact prose with these meta-descriptions. They write texts that need to be explained, like some artworks, to make sense. Galeta is an artist, so his performative explanations seem to be intentional. He’s like a wise fool, laughing at our ability to find pseudo-rationalizations for the things we fail to understand.

Leave a Comment