Thirtytwo years after the Soviet Union ended its intervention in Afghanistan – a collective trauma that contributed to the downfall of the USSR – the West terminated its own geo-political venture in the country. The outcome of the operation is as senseless as it is devastating. Since 2001, tens of thousands of civilians have lost their lives; countless have been injured, raped, and traumatized; millions have fled; hundreds of suspects – in many cases innocent – ended up in Guantanamo under inhumane conditions; and a whole country has spent years in a warzone and under occupation only for the Taliban to return to power the instant the NATO coalition left. In the countries that orchestrated the war, it is the long list of casualties among their own servicemen – of course not nearly as long as that of Afghan security forces – and trillions of dollars spent that have reignited doubts about the purpose of the mission. (Fittingly, the Western film industry – mainstream or not – has addressed the devastating effects of the Afghanistan war mainly through the lens of foreign soldiers and journalists experiencing it, thus allowing viewers to conceptualize violence through resultant traumas among servicemen and reporters and hence as a moral and psychological burden the West must stem. An alternative approach, hailing from Poland, is laid out in Jerzy Skolimowski’s Essential Killing.) Even though there is much political talk today over the way that the operation was terminated, the goal to retreat from Afghanistan as soon as possible was shared even by the eternally opposed Democrats and Republicans in the US.

Not all alliance partners have been on the defense regarding their participation in the US-led intervention though. On the 21st of July 2021, the Romanian Ministry of Defense hosted a military parade to mark the end of the Romanian mission in Afghanistan. The ceremony was attended by Romanian president Klaus Iohannis and other high-ranking officials and staged in front of the Romanian Arch of Triumph, which is dedicated to the “heroes of the War of Independence and World War I”. That the venue of the parade celebrates Romania’s implication in WWI as a heroic deed, full stop, is a fitting metaphor for its absurdity. A mission that harmed the Afghan people and was opposed by Romanians – as early as 2011, 67% of Romanians were in favor of a (partial or total) withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan – is here celebrated as a historic achievement.

The causes of this curious show of pride can be retraced to the beginning of Romania’s Afghanistan mission. When Romania joined the US-led intervention in Afghanistan in 2002, Romania did so “for the consolidation of the national position as a NATO partner”. Romania was not a NATO member at the time, and the intervention is generally believed to have helped accession in 2004. Why Romania continued to be overeager vis-à-vis NATO demands (e.g. by deploying the fifth-most troops in the entire alliance before withdrawal and participating in the missile defense system) is a different story, though it is clear that geopolitical considerations, notably Romania’s involvement in Black Sea diplomacy, continued to play a role. Financial considerations also play into Romania’s US- and NATO-friendly attitude. In 2019, Romania received the largest US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation grant in the world ($500,000) for restoring a medieval church. The US also ranked fifth highest among foreign investors in Romania that year (when European subsidiaries of American companies are taken into account).

As opposition to foreign interventions grows in the West, Western NATO members are increasingly looking for ways to offload a part of the financial and collateral burden of its ventures eastwards. This works best in countries which are dependent on Western investments, grants, and loans, which can be diverted to different areas (and pockets), including cinema. Though military interventions continue to be unpopular among Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europeans as well, keeping the fear of a Russian intervention constantly alive helps justify massive spending in the sector (in Romania’s case, it stood at 2.3% of GDP in 2020). And then there’s the yearning for national sovereignty and strength in many countries of the region, which is ironically fulfilled by promising ultimate subservience to NATO, for instance by participating in the devastating invasion of Afghanistan.

It seems, then, that the economic and nationalist pull of interventionism has not lost its appeal yet. While Romania’s military celebration is a particularly obvious display of this continued appeal, the resurgence of films and media coverage on the uncertain role of women under the Taliban not only downplays the violence women and society at large were being subjected to during the US-led invasion of Afghanistan. It also bolsters the myth of the world only being a safe place when secured by the watchful eyes of Western geopolitics.

***

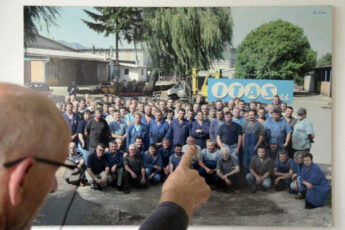

Our September issue features a review of Vlad Petri’s The Same Dream, a short which weighs the cost of Romanian “solidarity” with the US invasion of Afghanistan. Zoe Aiano, who reviewed the film, also spoke to its director Vlad Petri about the film and false perceptions of Afghanistan as part of her coverage of the Sarajevo Film Festival. From Sarajevo, we also bring you a review of Factory to the Workers, a documentary about a worker-owned factory, and an interview with its director Srđan Kovačević. Mihai Fulger was at the Pula Film Festival 2021, where he saw Zrinko Ogresta’s A Blue Flower and where he spoke to the event’s new artistic director Pavo Marinković. Finally, Daniil Lebedev initiates our coverage of the Biennale, which will continue into October, with a review of the Russian Pavilion’s special film program and its take on intersections between the digital and the real.

We hope you enjoy our reads.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment