Scenes from a Divorce

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless (Nelyubov, 2017)

Vol. 77 (September 2017) by Moritz Pfeifer

Ever since Leviathan, Andrey Zvyagintsev’s portentous epic about an everyman’s disastrous quest against the almighty state of Russia, the filmmaker has established himself as one of the most significant directors working today. Indeed it could be said of Leviathan that it is not only indebted to historical greats such as Bresson, Antonioni and Tarkovsky, but that it is a film that lies in their succession. Whether this can be said of his other works, and especially about his new pic – the terrifying and ominous Loveless – is debatable though.

In Loveless a boy called Alyosha disappears in the midst of a dramatic break-up between his parents. His mother Zhenya (Maryana Spivak) and father Boris (Aleksey Rozin) are too busy forming new romantic relationships to care for the unassertive demands of the twelve-year-old. When the couple occasionally meets in their once-shared apartment, it is to let in potential buyers or lock horns, but certainly not to take care of Alyosha. On one such occasion, while the parents engage in a heated argument over who should bear the burden of custody rights, the boy inaudibly screams in the bathroom and is so symbolically rendered invisible. The next day, he really vanishes.

The disappearance forces Zhenya and Boris to put themselves aside for a while and concentrate on the runaway. Surprisingly, the police won’t offer much help – though the corrupt officer is honest enough to tell troubled Zhenya that she shouldn’t expect any, giving her the advice to seek aid from civil society. Enter “coordinator” (Aleksey Fateev) and his highly competent search and rescue team. With the expertise worthy of the military, they turn the neighborhood upside-down, leading the divorced couple through abandoned sports facilities, hospitals and morgues, only to find nothing.

The film’s crime-film tropes also work as a pretext to delve into the deeper sloughs of the characters and Russia’s social order. Indeed, Zvyagintsev may be less interested in finding out “who done it?” than to ask what conditions would make people stop loving those that are closest to them. Perhaps the blame for the boy’s tragic fate is bigger than what a family can account for. Quite generally, Zhenya and Boris’s lovelessness outreaches their hatred for each other; love may be built on grounds that make it impossible to flourish.

And yet, for all its larger-than-life implications, the film never manages to kick off as another Leviathan, instead turning into a domestic drama. Zhenya and Boris soon pick up where they left off, throwing meaningless accusations at each other. Driving back from her mother’s place, Zhenya’s I-never-loved-you rampage, in which she reiterates that she never wanted to have a child, prompts Boris to leave her in the middle of the road. But neither the conversation nor its outcome reveal anything new about the characters. Zvyagintsev has already made it clear that they didn’t love each other.

Instead of humanizing his characters by letting us take part in their thoughts and struggle through more significant dialogues or having them confront society’s general lovelessness through the interaction with other people, Zvyagintsev relies on suspense and action-driven personality traits to make his characters look more complex than they are. Zhenya’s incessant urge to take selfies, for example, may not give a more complete impression of her self-obsession. For that she would have to drop her iPhone and engage with the other selfie-taking cuties sitting across the room…

Some of the strongest moments in the film are thus those in which Zhenya and Boris do engage with society. In one truly magnificent scene Boris talks with a colleague about the best strategy to keep the separation from his wife secret from his boss, who, as an Orthodox, has an employment policy that does not hire divorcees. But what, one may ask, would Boris have to say to the coordinator who seems to care more about finding Alyosha than himself? What does the teacher, as another representative of the officialdom, have to say about Alyosha’s disappearance? And what, finally, do the couple’s new lovers feel about the missing child?

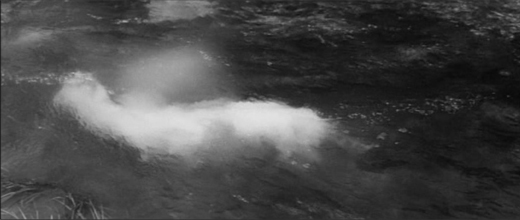

The film’s masterful cinematography and symbol-ridden iconography fall short of compensating for these narrative gaps. As in his other films, Zvyagintsev heavily borrows from the iconography of Tarkvosky. Already the first scene, in which Alyosha strolls through a nearby forest and discovers a piece of barricade tape in a pile of leaves which he then drags through the water of a nearby steam, is heavily reminiscent of a scene in Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev. In the Tarkovsky film, Foma, Rublev’s apprentice who is played by a blond-haired boy like Alyosha, cleans his brushes in a river and the camera pans to a beautiful milk-like substance floating upstream. Later in the film, when Foma is killed falling into a river, the substance appears again. The form and movement of the milky substance and the tape, the contrast of placing an unnatural element in nature, as well as the look and age of the boys starkly resemble each other. In both films, the symbols also appear twice, each time framing the lifespan of the characters (although this is less clear in Loveless since we are not entirely certain that Alyosha is really dead).

Foma’s death in Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev and the opening scene of Loveless

Much could be said about the Tarkovsky scene. Perhaps the white substance simply represents the colors of Foma’s paint, and their dissolution in the stream at the moment of his death, the boy’s unlived life as a painter. On a more metaphorical level, the scene could also give an image to ideas about the fugacity of life. It evokes the idea that nothing in life stays, that all things in life are fleeting. Heraclitus’ famous dictum that you cannot step into the same river twice involuntarily springs to mind. Associated with the milky substance itself – milk traditionally being a symbol of fertility and abundance – the death scene strikes us as particularly brutal. Whatever you make out of this metaphor, however, it is deeply connected with the character himself and with what happens to him in the film, his prolific life and tragic death all coming down in this one moment.

The same cannot be said about the way in which Zvyagintsev uses the barricade tape in Loveless. At best the tape foreshadows the boy’s disappearance and, possibly, his fate as the victim of a crime. But the metaphor is not connected to Alyosha’s experience of life as the milky substance in Tarkovsky’s film is to Foma’s. As such, the image simply strikes us as a cinematographic citation. It would have been more adequate to come up with a metaphor that could give an image to Alyosha’s experience of life. That is why the strongest moment in Zvyagintsev’s film is perhaps Alyosha’s silent scream. It directly represents the child’s experience of neglect, of not being heard. The scene is so brutal because it makes us realize that it wouldn’t make a difference if his scream had a voice.

There are other scenes in the film in which Zvyagintsev’s extremely well-crafted images may defeat their purpose. To cite a last example, consider his use of Dutch masters, in particular those of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (yet another indirect indebtedness to Tarkovsky). There are two scenes which are very reminiscent of Brueghel’s winter paintings like Hunters in the Snow, his winter landscapes with skaters and a bird trap and of his autumn paintings like the The Hay Harvest or Harvesters, all of which were painted 1565. In Loveless, both scenes are used to mark passing time. Zvyagintsev’s film starts in autumn. Alyosha walks home from school and then sits in his room staring out of the window. The landscape in front of the house looks over a meadow and leafless forest, and children are playing all over the place much like in the Brueghel paintings. Later in the film, we are again in Alyosha’s room which is now being renovated to make room for the new owners. Winter has come, and the camera pans out of the window over the same landscape, which is again full of snow.

Brueghel’s Hunters in the Snow, the two Brueghel inspired scenes in Loveless and Tarkovsky’s Mirror

Tarkovsky quotes Brueghel’s winter paintings directly in Solaris, where Hunters in the Snow is onboard the spaceship, and indirectly in The Mirror, in a scene were a bird flies on top of a boy’s head. In this scene, the narrator recalls a childhood memory of the Second World War to his son, Ignat. Before the memory shot, we see Ignat on the phone, so it is ambiguous whether the images represent Ignat’s impression of his father’s story or if they represent the father’s memory itself. Either way though, the images are disturbing because their beauty and peacefulness – what wars would give birds the serenity to take a rest on a boy’s head? – starkly contrasts with the brutality of parts of the narration and the archival footage of newsreels of World War II, the Spanish Civil War, and the Sino-Soviet Border Conflict used in the same scene. The reconstruction is artificial, and yet it gives an image to the emotional state a child might have experiencing war. The themes of calmness, innocence, and purity that come from the Brueghel painting may thus represent an idealized version of Ignat’s father’s childhood before the war. As such the scene is also a reflection on how we create memories, and even on creativity itself. It is important to note, that art and beauty, for Tarkovsky, are deeply connected to human suffering and our moral understanding of the world. In an interview for a documentary portrait, he reasoned that “the artist exists because the world is not perfect. Art would be useless if the world were perfect, as man wouldn’t look for harmony but would simply live in it. Art is born out of an ill-designed world.” In other words, the beauty that comes out of the Brueghel scene may also be a reflection on the artist’s desire to create harmony out of chaos, to contrast the destructive experience of war with the assertion that if beauty exists, so does the good.

Like Tarkovsky’s use of metaphors his references to Brueghel are intricately connected not only with the characters and what is happening in the film, but also to his ideas about aesthetics. Again, the same cannot be said about Zvyagintsev’s use of the Brueghel references. While Alyosha looks contemplative over the landscape, we don’t know what he feels about the scenery. Does it strike him as beautiful? Does it make him feel melancholy with regards to his own feelings of loneliness and unrest? Who knows. In the winter scene too, it is hard to come up with an interpretation that goes beyond the observation that time has passed. Alyosha being gone, there is nobody there to contemplate the scene. Lacking the aesthetic vision of a Tarkovsky, the references merely demonstrate Zvyagintsev’s refined taste in art.

Loveless is an ambitious project and Zvyagintsev’s talent can certainly be recognized in many scenes. Perhaps too much pressure was put on him to deliver something great after the acclaim of Leviathan, and the director did not have enough time to refine his script, reverting instead to more conventional means of storytelling. It may also be noted that the film, unlike his previous ones, had to pool in money from different countries (France and Belgium), which could give an explanation to the action-driven plotline that is untypical for the director (as well as to the bluntness of his political criticism, ie. the Russia tracksuit). One can only hope that his upcoming projects will look for depth in what Zvyagintsev himself once called “the human condition” instead of trying to turn a Kammerspiel into a Rennaissance painting.

Dear,

I’m currently doing research into Breugel in film. In your essay you mention the Zvyagintsev’s reference to Tarkovsky and Breugel, which is very interesting for my research. I’m interested in how Tarkovsky read Breugel and how Tarkovsky influenced other film makers. The Belgian painter Michael Borremans refered to Tarkovsky and Bruegel as a source of inspiration in a recent interview. Has Zvyagintsev mentioned Tarkvosky and Bruegel in an interview or can I find his reference in print?

Thank you very much in advance and kind regards

Maarten Daens

Master Student Art and Archeology – Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Hi Maartens, I’m not aware of Zvyagintsev mentioning Brueghel, but the director mentioned Tarkovsky to me in an interview once. https://eefb.org/interviews/andrey-zvyagintsev-on-elena/ Good luck with your research!