This year Berlinale Talents, the talent development program of the Berlin International Film Festival, focuses on the theme “Labours of Cinema”. With this choice the Berlinale wishes to raise awareness that a film is “the product of many, and the labor and working terrain of various professions and crafts.” This heavy-weight topic, the social question of culture, is certainly prescient. In the city hosting the Berlinale, the working conditions in film and television are notoriously precarious. According to a recent study by the parliamentary group of DIE LINKE (“The Left”), only one third of employees in the industry were able to live off their income. Another worrying factor is that much of the labor in cinema is commissioned as temporary employment without contractual security, standard rates and overtime pay. Despite local unions such as the filmunion or initiatives like art but fair calling for compliance with collective wage agreements, 68 percent of respondents in Berlin-Brandenburg stated that their working contracts disregarded collective agreement regulations on payment, overtime or working on Sundays and public holidays. With the income pyramid being especially penalizing towards the young, many believe that they have made no pension provision for old age. Lastly, there are extreme differences in income between “male” and “female” jobs, with women earning about 30 per cent less than men.

In light of precarious employment conditions and income inequality in the film sector, the choice of this year’s Berlinale Talents theme is a welcoming move and could provide an opportunity to encourage political pressures in negotiating fairer employment standards in the sector. It is therefore all the more bewildering that the organizers of Berlinale Talents do not appear to understand “labour” in the economic sense of making a living, but in the creative sense where, apparently, money plays a secondary motivation, if any. Asked what “labours of cinema” means to the selection committee of Berlinale Talents, the idea that work means pay did not cross the respondents. It is worth quoting the replies:

Gabor Greiner: To me it means what the magic and power of cinema can achieve and how it can help to not only change mentalities and educate but also to transform, enchant or simply entertain.

Dana Linssen: Labours of cinema are always labours of love. We cannot create if it is not out of love, and like love, these labours are multifaceted and colourful and sometimes painful. A labour can be hard work, or a test of our endurance. It can be gratifying to see the result but sometimes the process alone makes it worthwhile. Working in cinema becomes a kind of philosophy of life, and for the etymologists among you: there is love in philosophy, too.

The idea that art is too important for the mundane and morally inferior activities of individuals in need for money is, of course, not new. One need only think of Carl Spitzweg’s painting “The Poor Poet” to understand that creative self-realization comes hand in hand with an aura of exclusiveness and self-sacrifice. Nevertheless, Spitzweg was bold enough to call his poet “poor” instead of “magical” or “loving”. More than raising awareness for grievances within the film industry, the Berlinale’s discourse on labor appears more likely to legitimize forms of exploitation by framing poverty as a creative or psychological opportunity for self-growth instead of an economic condition to overcome. Such a blending of moral and economic categories may thus reinforce the exploitative tendencies of the work environment by aestheticizing labor, or by what the German sociologist Andreas Reckwitz has called the “creative dispositif”, i.e. a process in which non-aesthetic phenomena such as employer-employee relationships are aesthetically transfigured or romanticized. In such a dispositif, creative work is above all a promise of freedom and self-fulfillment and not a question of fair pay.

How likely is it that, say, a director participating in the highly competitive and selective Berlinale Talents, will admit that they are spending the little money they are getting to make a film on everything but fair pay; that two or three side jobs are necessary to make a living; that being creative means working, exhaustively and with noticeable imperilment of one’s health, at night and on weekends; that even applying for the Berlinale Talents – a full application running some ten to twenty pages – means to take unpaid leave and that a successful application and the attendance of the Berlinale Talents means yet more unpaid leave. All this is hard to put into words when the said director is encouraged to understand his or her labor as love, the participation at the sought-after event as a pay-off of success, creativity, and inclusion. In this way, the economic hierarchy of being poor oddly contrasts with the moral or political hierarchy of success and the institutional distinction between the “deserving” and the “undeserving.” That one is more likely to accept the latter so as not to raise suspicion and be shamed for being poor is a form of symbolic violence. It legitimizes social hierarchies – not only in the eyes of the dominant, but in those of the dominated as well.

This leaves little room for a meaningful discussion on the social question of labor. Indeed, there is an awkward cognitive bias at stake in such lofty claims of cinema’s purported “labours of love”, considering that film festivals are the forefront of sustaining precarious working conditions through the (self-)exploitation of thousands of festival workers. As we have highlighted in last year’s editorial, the Berlinale is no exception. This year again, its interns can expect to earn 225 euros for two 39 hour weeks (interns are expected to be fully available during these two weeks, including on weekends). Most festival workers, as pointed out by the trade union ver.di, who has created a special commission for festival workers in 2016, are highly specialized professionals with a university degree and professional experience. However, they are supposed to be flexible at all times, and accept to be precariously or arbitrarily employed on a temporary basis, underpaid and beyond the scope of valid labor laws.

While a cognitive bias may apply to the Berlinale Talents, the fact that the Berlinale endorses such a “creative dispositif” while the wage ratio (the difference between the wage of festival director and intern) of the festival is 59:1 (when internship pays now are measured against the 2020 public record of employees of the state), makes it look more like a form of organized hypocrisy. While the Berlinale has the reputation of being the political festival among major film festivals, this certainly does not apply to its views on labor politics. With poor pay and low job security, the festival is actively sustaining precarious employment conditions and income inequality. And so another question, which one can only hope will have been asked – if not during the official events of the Berlinale Talents, then at least in the corridors and after-“work” parties – comes to the table: what are art and culture actually worth to us as a society? A substantial debate about this is not only necessary for economic reasons. Cultural policy is called upon to take a stronger stand.

***

In late January, we were at the Trieste Film Festival, where we saw Paweł Łoziński’s film of the hour – which was entirely shot from his balcony -, and Danis Tanović’s light-hearted take on regional conflicts on the Balkans. Jack Page has been reporting from the Rotterdam Film Festival, where he saw Alexander Zeldovich’s adaptation of Euripides’ Medea, as well as Maria Ignatenko’s reckoning with the role of nostalgia and accountability in our relation to WWII in Achrome.

We are also publishing two reviews by Maxim Plokhikh of films he saw at the Biennale last year. Those were Ekaterina Selenkina’s Detours, which explores Moscow’s urban environment through the daily routine of a drug dealer, and Péter Kerekes’ 107 Mothers about convicts who are raising their children in an Odessa prison. Equally from the past few months are Melina Tzamtzi’s reviews of World, Christine Haroutounian’s short about coping with grief, and Kornél Mundruczó’s Evolution, which deals with historical traumas. Both articles were written at the Golden Apricot Film Festival 2021, where we also interviewed Christine Haroutounian.

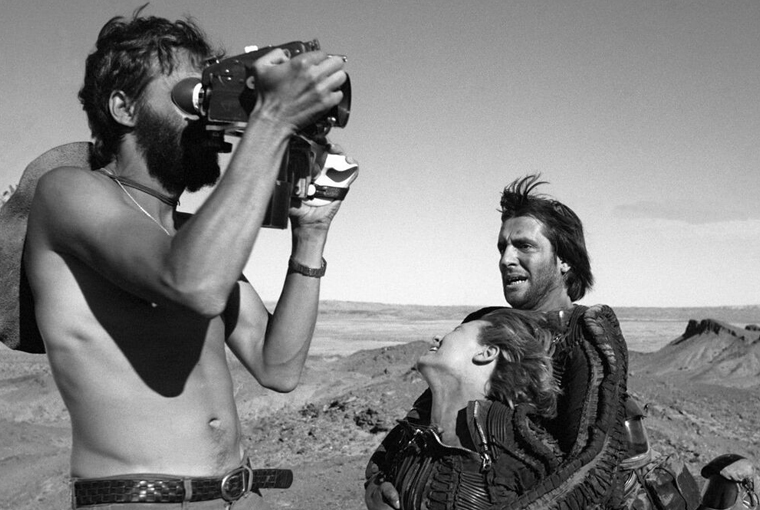

Finally, Lucian Tion reviewed Kuba Mikurda’s Escape to the Silver Globe, which is a reassessment of the political context Andrzej Żuławski navigated during the (failed) production of an ambitious sci-fi film. You can find an interview with Mikurda about the political and aesthetic context of his documentary in our Interviews section.

We hope you enjoy our reads.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment